When we think of those who protect us from bush fires, it is natural to think first of the firefighters.But there is another group of unsung heroes amongst us. Equally important, are the sentinels – the anxious, the Worriers.

Again, we all know people like this. You may have one in your family, or amongst your friends or colleagues; you may be one yourself. These are the people who warn us of impending danger, who think the worst, imagine the unthinkable, and constantly say: ‘Watch out for this; don’t do that.’

Rather than being a handbrake on fun, these are the people who prime us for action. Like the Warriors, they were born this way and have an innate ability to perceive threats more quickly than others.

Dr. Bruce Buckley, whose account is on page xiv, is a professional worrier. He is a meteorologist who works with IAG to study weather patterns and climate change and forewarn us of potential threats in time for us to take action. He was amongst the first to warn Australia of the coming billion-dollar fire season. He had viewed the weather patterns, read the data and could see what was coming like an omen. Just like the birds that leave long before a disaster strikes, he was our early warning.

In Tsachi Ein-Dor’s paper, “Facing danger: How do people behave in times of need? The case of adult attachment styles”, he explains that there are three types of people essential for success in group responses to danger. Each is genetically different and perfected through evolution.

While the anxious amongst us are often perceived as highly stressed and are rarely seen as helpful in times of crisis, it is their ability to forewarn others that allows the group to respond faster and organise themselves when something bad does happen. In this respect, the Worriers are invaluable.

We know through studies of 9/11 that two-thirds of the people in the buildings only became aware that something was wrong because of the actions of the anxious, who grew hysterical and started a mass exodus. Those anxious people may have saved more lives than the firefighters and other first responders.

Australian communities are exposed to just about every hazard this world can throw at them: from earthquakes to storms and cyclones, to bush fires and devastating floods.

Mark Leplastrier, Executive Manager, Natural Perils, IAG

We really need to appreciate that climate change is real. It’s not only real, it’s here right now and it’s accelerating. It’s up to all of us to try and do the right thing to combat climate change – not only in our own interests, but in the interests of our children and our children’s children.

Dr. Bruce Buckley, Specialist, Meteorology, IAG

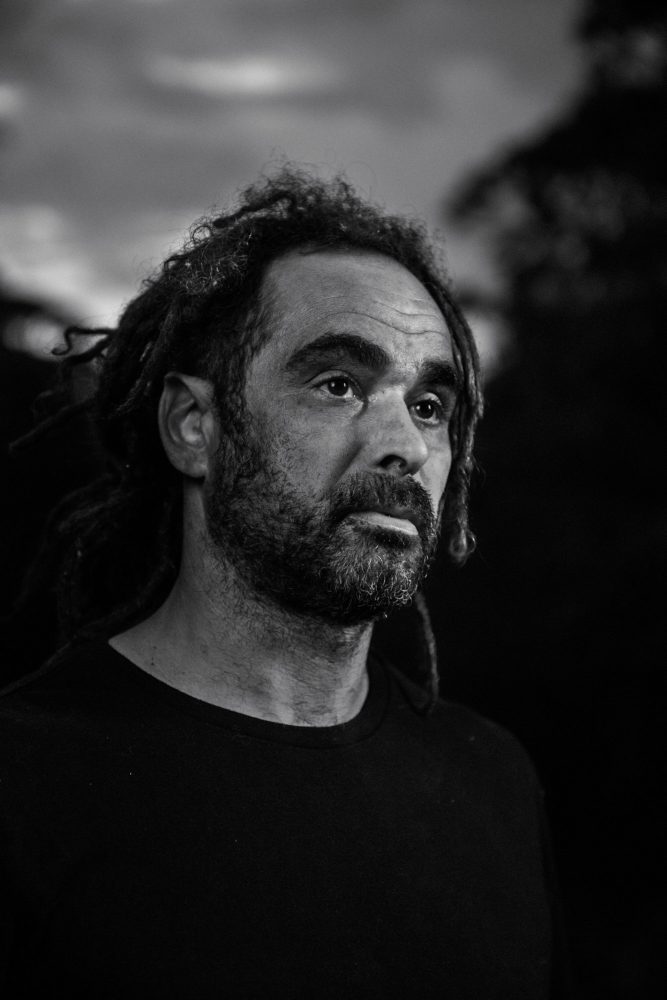

Dan Morgan

Traditional owner

Djiringanj Yuin, Bega Valley, NSW

“Cultural burning is the traditional fire regime of Australia that was implemented thousands of years before colonisation.

Within the last 200 years, though, it hasn’t been practiced, so the landscape has been mismanaged and I feel that is a big part of why we’re getting these mega-fires.

We need to maintain Country through traditional fire; this practice has always maintained the health of the Australian landscape. It’s the way we’ve managed land for thousands of years, it’s a living spirit within our culture.

If you use it the wrong way, then it can be devastating. But when you use it the right way, it becomes your friend and you learn to respect fire, instead of being scared of it. You have a mutual relationship with it.”

Rachael Cavanagh

Minyungbal Traditional Owner, Tweed Coast, NSW, and Community Programs & Stakeholder Engagement Manager, Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation

I am a proud Minyungbal wajung, mother, from the North Coast of New South Wales. I’ve spent most of my life living in Yuggera, Ugarapul, Yugambeh and Bundjalung countries and have a strong cultural connection to my homelands. I have worked in the environmental industry for twenty years, in both the private and government sectors, and across different land managers, in various roles.

Throughout my professional development, I’ve gained extensive insight into the western methodology around management of Country. Walking in two worlds can have a heavy impact on you as a First Nations person. After the Black Summer, I found it difficult to stay in a government agency that continues to disregard First Nations management of Country. I started my consultancy business to support First Nations people to develop and implement Caring for Country programmes grounded in cultural framework. In 2021, I started working for the Firesticks Alliance Indigenous Corporation as the Community Programs

& Stakeholder Engagement Manager.

During the Black Summer, I was working for the Forestry Corporation of New South Wales as an Aboriginal Partnerships Liaison and full-time firefighter. Our fire season kicked off in late July 2019, and by August we were already seeing crown fires. We knew we were in for a big season, but didn’t realise just how severe it would be. Country was burning well before it reached the South Coast in December. Long days turned into long weeks that seemed to last forever, month after month. As a firefighter, you turn up to your shift, continuously listening to weather updates on the news. In the back of your mind you’re thinking of your family and friends, hoping everyone is safe.

The fires were so intense; the roaring sound and how fast they moved. The forest was completely destroyed, whole ecosystems lost. The screams of animals being burnt alive is a sound I can’t forget. The devastation left behind; Country was unrecognisable. We lost the forest, but we also lost our cultural heritage. Our boundary markers tell us where we can and can’t go, where you point out to your jarjum, children, certain points not to pass, where Country starts and ends. Areas where we knew we could hunt and gather native foods and weaving materials. The last remaining remnants of our old people were gone. Country was crying, my spirit was crying. I felt enormous loss for my people and our land, and pressure that this all could have been avoidable.

Country is everything. It’s the plants and animals, it’s our language, song and ceremony, it’s the land, water and the elements. It’s our connection to our kin. I encourage all people to know the Country they live on, and to educate themselves on First Nations people and their practices. We are the most researched people in

the world; there are more than enough resources out there for people to learn our history. Know the places and people of the Country you call home, reach out and immerse yourselves in this deep history. Read Black literature, go to community- organised events, look for cultural burn workshops or community days in your area.

Today still, Country is sick. Bringing back cultural burning practices will help us reset, but it is going to take time. Generally speaking, cultural burns are a series of spot ignitions set in a mosaic style allowing fire to move freely through Country, leaving unburnt areas for critters and animals to move out of the way and then later return and feed. These cool, low-intensity burns create good smoke and prevent topsoil from burning, allowing for seed banks to remain intact. Essentially, it’s the right fire for the right time. But there are many layers to the process of cultural burning, and the outcomes can differ each time. You have

to know Country and be able to read it. Depending on the landscape, terrain and weather, there will be different fire patterns.

Our old people had a good relationship with fire. It was used for hunting, ceremony and keeping camp areas and grassy pathways clear. This practice has been around for millennia; it is not a new technique. It is part of bringing back the old ways, to properly care for Country. Cultural safety of our people is paramount, and it’s rewarding to see these traditions brought back, and to see Country and communities responding positively. It’s healing.

Maree and Michael Fletcher

Maree and Michael Fletcher lost everything they owned in the Currowan fires – their house, their cars, their personal possessions. They lived in the small community of Conjola Park, NSW, located between Batemans Bay and Nowra, just a three-hour drive from Sydney, NSW. Once a thriving holiday town which saw tourists flock to the area in droves, it was home to less than 500 permanent residents.

On New Year’s Eve 2019, sudden and brutal fires swept across the South Coast of Australia, engulfing the communities in their path. Conjola Park was one of these communities, and it was largely incinerated as a result. Lush greenery was reduced to blackened tree stumps and skeletons; sturdy buildings were reduced to rubble across the town. For days after the fires, thick smoke hung in the air, shrouding the landscape in grey as residents tried to pick up the pieces, many without power, safe drinking water, working phones or petrol. The one road in and out of Conjola Park quickly turned into a queue of desperate evacuees trying to escape.

Maree wasn’t at her home when the fires stormed through; she was at her parent’s farm nearby, trying to put out the containment lines the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) had lit in an attempt to slow the fire’s spread. As she drove back to her house, she began fearing the worst for her husband, Michael, and their eighteen-year-old son, Zac, and her father Reg, whom she had left behind. In a panic, she drove to the nearby beach with her twelve-year-old son Riley and her mother Robyn, as this was the only safe place she could find. Several hours later Michael and Zac found them huddled on the lake-shore – frightened, but safe.

Debris now litters the ground where the Fletcher’s house stood. Part of a scorched brick wall, a pile of crumpled corrugated iron and the empty shells of burnt-out cars are all that remain. The family is in the process of building a new home.

Maree and Michael Fletcher survey their destroyed property in Conjola Park, NSW on New Year’s Eve 2019.

Members of the McDermott and Fletcher families whose houses were destroyed in the Currowan fire, console each other for their loss.

Happiness is not about the ‘stuff’. When you nearly die, and then you don’t, you know that it’s not about your possessions. Whilst we can’t always control what happens to

Petrea King, CEO, Quest for Life Foundation

us, we always do have control over how we’re going to respond to what happens to us, and in that lies a huge point of power. Because it’s appropriate to weep about,

rail about, scream about, write about, talk about whatever happened, until you can

get to a place where, ‘Yeah, that did happen, and it happened to me. But I’m living with the wisdom gleaned from that experience. I’m no longer living with the wounds of it.’

Worzil Shaw leans against his favourite burned out ute. Shaw became a local hero when he remained behind after an evacuation order and successfully defended his Mogo property and several others, all whilst barefoot, when the Currowan bush fire hit the area on New Year’s Eve 2019. Mogo, NSW, January 2020

Barbara Stewart

Resident, Nerrigundah, NSW

I always say, ‘There’re others out there worse off than what we are’.

They’re still living in tents. And we were fortunate, we were given a pod, but we felt very guilty about having it. We didn’t really need it, we’re okay. There’s always somebody out there worse off than you are.

And if you think too much about what you’ve lost and that this shouldn’t have happened, it’s a silly attitude, because you’re alive. A lot of people lost lives, but you’re alive. You just get up and get on with it.

And then, if there’s something and someone needs it and you can share it and give it, give it.

Burned bushland in the Blue Mountains, NSW. March 2020

Locals visit swathes of land devastated by bushfires in 2019 to assess the damage to the environment. Northwest NSW. 2020.

Charred remains of once lush forests are all that remain of Bago State Forest and bushland around Conjola in NSW. 2020.