Peru is home to the world’s largest number of alpacas. The country has approximately 4 million alpacas, which is roughly 88% of the global total. Alpacas are reared in high-altitude regions in Peru, generally above 3,000 mt. The animals play a critical role in communities along the high Andean plateau where crops cannot be grown and the only economic activity, besides mining, is alpaca herding. More than 1 million people, in a country of 33 million people, depend exclusively on alpacas for their livelihoods.

Peru is on the list of countries most susceptible to the impacts of climate change

Alpaca flocks during transhumance

Climate change poses a growing risk to alpacas and the communities they sustain. The Andes are experiencing shorter, but more intense, rainy seasons, and longer periods of drought. Frosts and hail storms have become more common. Changing weather patterns are shrinking natural pastures and reducing the quality of grasses, forcing alpaca herds to compete for food. A looming impact is the loss of glacier coverage.

Glacier runoff helps regulate water during the dry season, so the loss of glaciers means less water during the dry season.According to the National Institute for Research on Glaciers and Mountain Ecosystems (Inaigem), Peru already has lost 53.5 % of its glacier coverage and could be without glaciers by 2100. Peru has the world’s highest percentage in the world of what are known as tropical glaciers.

A veterinarian from Descosur an NGO that works by supporting Alpaca breeders. Their work focuses on controlling births and giving veterinary medical care to the breeders. Medicines and consultations from private veterinarians are very expensive and so not all ranchers can afford it.

A newborn alpaca cub during transhumance

A dead alpaca inside the laboratories of the NGO Descosur

Portrait of a woman Alpaca breeder. Women are crucial to the herds of these animals; they are often in charge of grazing the Alpacas.

Portrait of a woman Alpaca breeder.

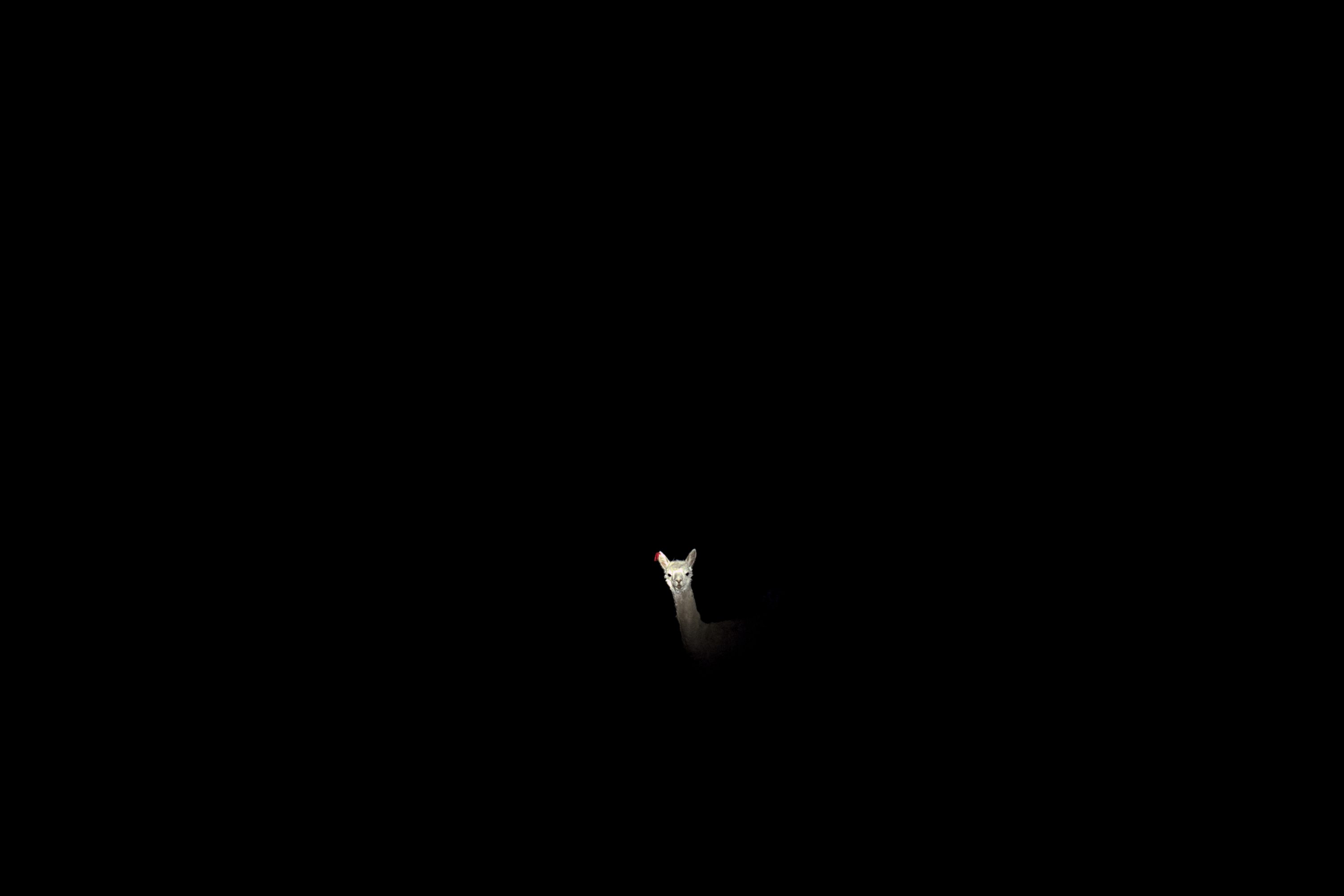

A herd of Alpacas spend a night on the mountainside exposed to the elements

Alpacas are considered one of the Peru’s main natural resources. They generate the meat and fibre essential to the economy of the high-altitude Andean communities. Alpaca breeders (Alpaqueros) are one of the poorest groups in the country and due to their economic situation, many cannot afford to build shelters to protect the alpacas at night. This exposes them to harsh climatic conditions found above 4000m, such as frost.

Sixto Flores, a technical advisor to alpaca communities in Puno, said if pastures disappear, alpacas and alpaca-herding communities disappear with them. With Climate change Alpaca breeders are becoming “climate migrants” who are forced to move to higher and higher altitudes or abandon their lifestyle and move to low-lying cities, changing their lives forever threatening the loss of high Andean cultural identity.

Alpaca breeders (Alpaqueros) are one of the poorest groups in the country and due to their economic situation, many cannot afford to build a roof to protect the alpacas at night.

A veterinarian cares for an alpaca, often the weaker alpacas are are given a coat to protect them from the cold, fed milk through a baby bottle and medicine through injections.

A veterinarian injects an alpaca

Alina's family gathers for the transhumance that will take place the following day. During the transhumance a lot of labor is needed because walking 300 alpacas for more than 6 hours is not easy. So family members get together to support the elders and people who have decided to continue with this work.

A man plays an instrument typical of Peruvian culture during the celebration of Pachamama

A family of Alpaqueros perform a Pachamama ritual.

A wedding between two Alpacas.

In the high Andean zones, local traditions are gradually fading away. Between the dry and rainy seasons, the whole community would thank Mother Earth (Pachamama), the mountain (Apus), and the sun (Inti Raymi) for the year’s harvest and grazing, sacrificing a small alpaca as a sign of gratitude.Today, these traditions are disappearing because the number of alpacas is decreasing as a consequence of climate change and the abandonment of young people from the countryside. Also, the increase of poverty prevents Alpaqueros from devoting time and resources to traditional festivities. Difficult living conditions mean that some rural people no longer feel grateful for the land.

The photo above shows a wedding between two Alpacas. This ritual is one of the rarest in the Peruvian Andes. Only a few families are left to perform it because of cultural loss due to migration and young people changing their lifestyles. At each change of season, families gather with neighbouring communities and organise a marriage between a male and a female Alpaca. This is done as a sign of hope for the coming season. For it to be good and without too much loss in terms of Alpaca life

An alpaca is sacrificed the day before transhumance. Alpaca breeding families organise transhumance four times a year, when they move to higher or lower altitudes depending on the climate and the season.

During visits by government personnel to rural areas, Alpaca breeders show the bodies of dead alpacas to them in protest. To do this they preserve the lifeless bodies of Alpacas.

A man during the Pachamama ceremony pours chicha, a typical drink, on the ground.

A man collects alpaca fibre.

A stock of a middleman's Alpaca skins.

The importance of middlemen (in Spanish ‘Acopiadores’) for the Alpaqueros has grown a great deal in recent years as a direct result of climate change and neoliberal economic policies. Families, who have seen a decline in their income, agree to sell

their fibre to middlemen, for an immediate profit, who buy it at a low price taking advantage of their plight. They sell the fibre onto multinational corporations who supply to foreign countries. In 2021, the number one consumer of Alpaca fibre was Italy.

Margaret Pilsen is a small artisan who makes handmade crafts from Alpaca fiber.

Yuper Quispe, 28, a third-generation alpaqueros taking photos for tourists

Yuper Quispe, 28, is a third-generation alpaqueros. His family has about 200 alpacas. He has no children and was born and raised in the community of Palcoyo. In recent years, Palcoyo Mountain has become a world famous tourist attraction visited by hundreds of people. He says that since the tourists have arrived, his earnings have increased through tips, and

every day he dresses in traditional clothing specifically to have his picture taken with his alpaca Raul. With the money earned from this new job, his intention is to move to Sicuani, a neighbouring village, change his life and leave the Alpacas forever. Life for the Alpaqueros is very hard, he says, especially because of the changing climate.

Young men looking at ads in a job centre in Cusco. Many young people, children of Alpaqueros, are becoming Climate Migrants, moving to the larger low-lying cities such as Cusco or Arequipa.

Alpaca beauty contests have increased greatly in recent years. Pictured is a Suri-bred Alpaca specimen, winner of two categories. Because of the contests some Alpaqueros are investing in this, completely changing the breeding of Alpacas. Many of them already do not shear the animals, but groom their fiber just to win. Once the alpaca wins they call themselves "Improved Alpaca" and are asked by other breeders to breed their cattle.

An alpaca, waiting to compete in a beauty contest.

View of the Quimsachata Research and Production Center.

A researcher at the Quimsachata Research and Production Center in Peru as she looks through a microscope in the in vitrio fertilization laboratory.

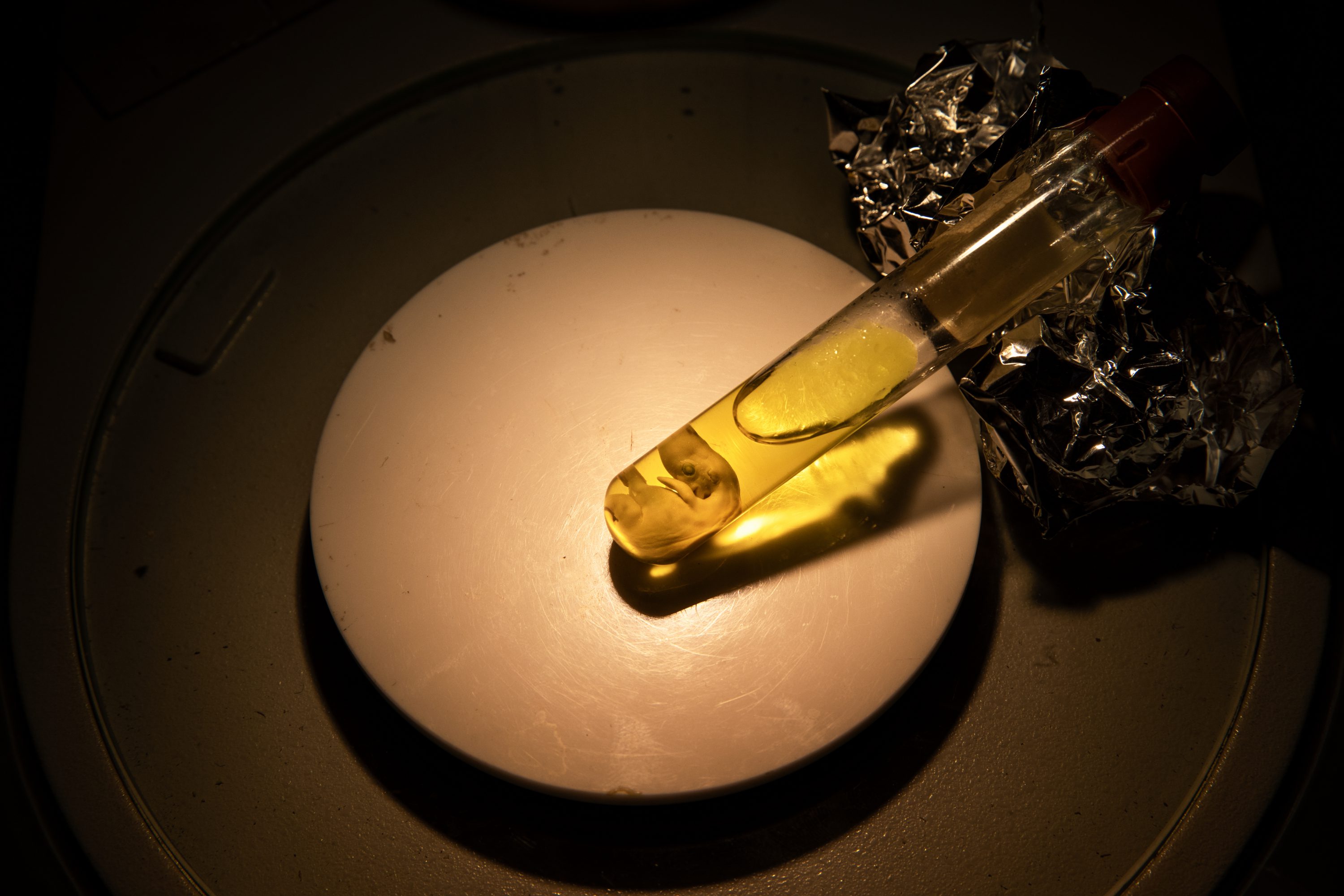

Pictured here are three Alpaca fetuses. Scientists at the Quimsachata Research and Production Center in Peru preserve aborted fetuses to study them and better understand the cause of death.

A researcher at the Quimsachata Research and Production Center, in southern Peru, installs a plastic vagina in an Alpaca dummy. This will be used to collect semen from a male alpaca that will then be used for insemination in the laboratory. Researchers select only the best males and females for breeding so that the next generation will have finer wool and greater resistance to climate change, according to Oscar Efrain Cardenas, national coordinator of the Quinsachata center's camelid program. This public center, located in Puno, aims to improve the production and productivity of alpacas and reduce the effects of climate change on the species.

Pictured is a detail of the plastic vagina that will be installed in an alpaca mannequin.

A female Alpaca dummy, used for semen collection, is prepared by researchers. Male Alpacas in the enclosure behind wait their turn to copulate

A medical team prepares an alpaca for surgery.

Peru’s Quimsachata Research and Production Center is home to the largest genetic reserve of alpaca breeds in the world. With state-of-the-art technology, the centre is attempting to combat the effects of climate change on alpacas. Changes in weather patterns have impacted their reproduction and survival. Through in-vitro insemination, the centre is attempting to

breed more resilience in the genes of the animals and improve their reproductive capacity. They’re also targeting the prevention and treatment of diseases that adversely affect the productivity of camelids. This female alpaca is being prepared for a laparotomy, which allows researchers to explore the reproductive organs and do a molecular aspiration.

A medical team prepares a female alpaca for a laparotomy, which allows researchers to explore the reproductive organs.

An alpaca fetus is analyzed under a microscope at the Quimsachata Research and Production Center in Peru. The center aims to genetically improve the breed by creating so-called "improved alpacas".Indigenous communities often raise money to buy one of these "improved" specimens, which are much more expensive than normal alpacas but more resilient, to incorporate them into their livestock.

A researcher at the Quimsachata Research and Production Center in Peru with a Pacovicuña specimen.

The Pacovicuña is a hybrid breed of alpaca created by mating an alpaca and a vicuña. At this centre, researchers were able to create 100 specimens of Pacovicuña that were put on an island to prevent adulteration of existing species. This breed has high resistance to cold and to the effects of climate change and has more valuable wool, according to Oscar Efrain Cardenas,

national coordinator of the Quinsachata centre’s camelid program. The crosses between alpaca and vicuña can also occur accidentally in remote places in the mountain range, when male vicuña are crossed with female alpacas. Pacovicuña’s fibre is more valued than alpaca’s since it has the fineness and silkiness of the vicuña and a longer length.