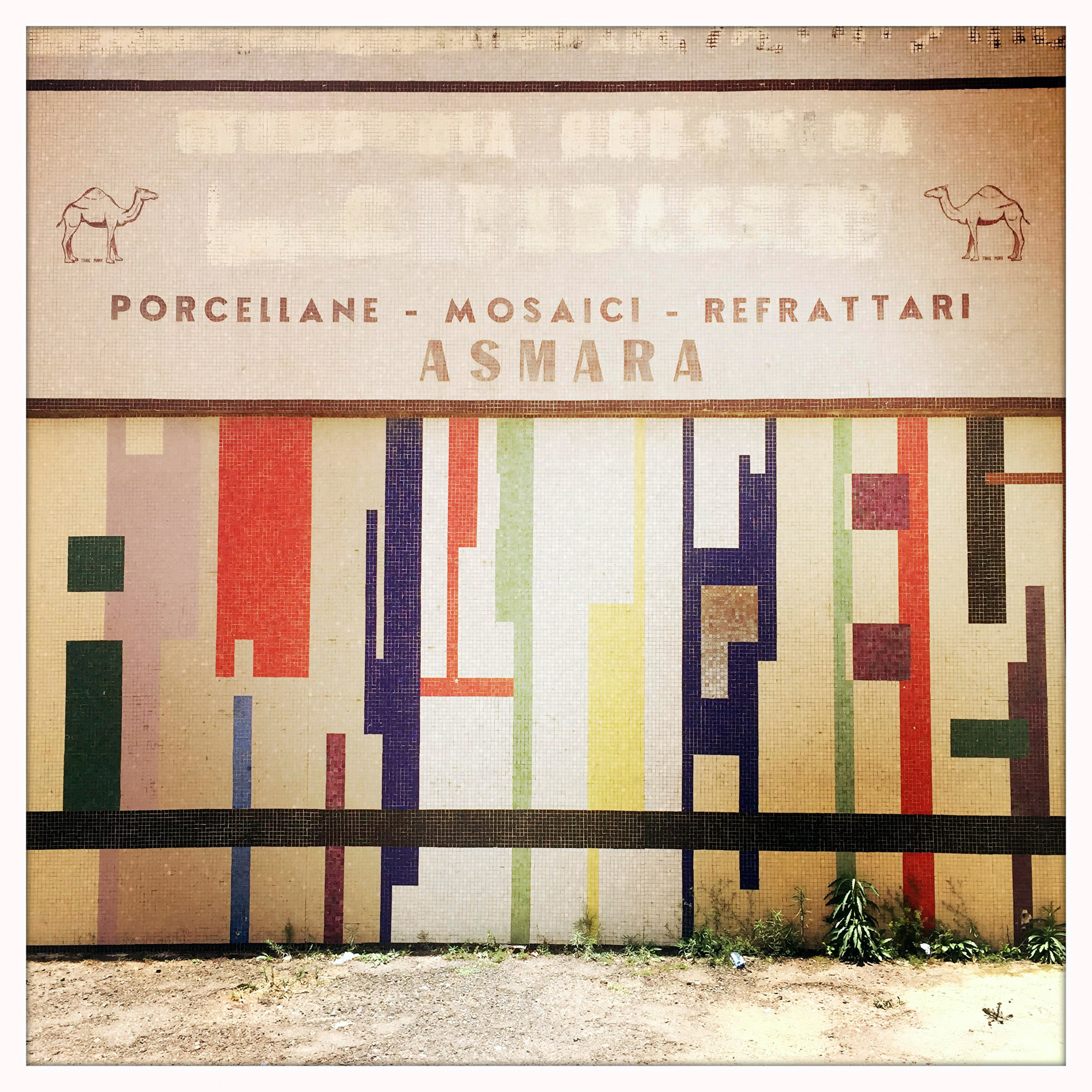

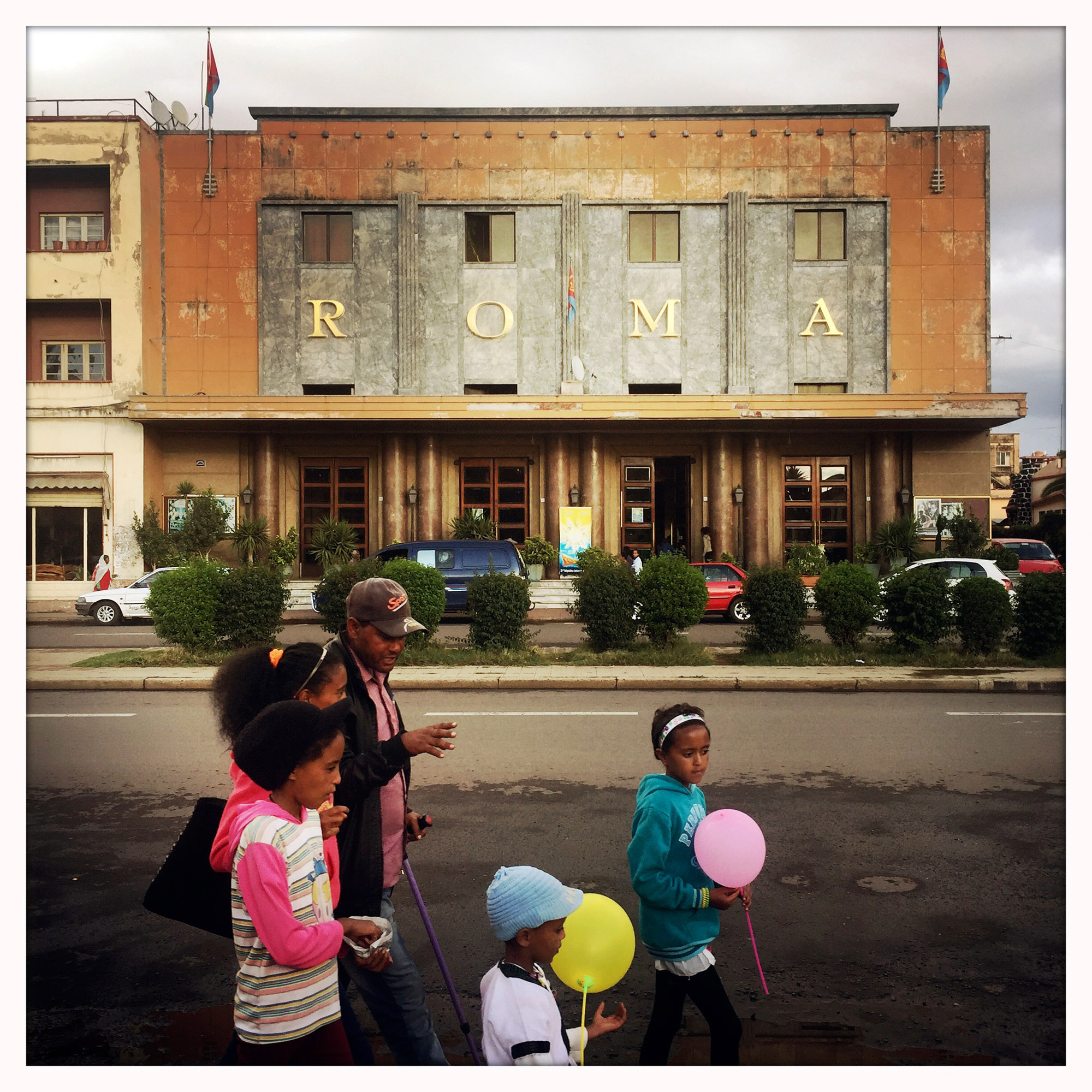

A photographic journey through the remains of Italian colonialism and architectural modernism in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea

Asmara is a prototypical postcolonial city with multiple contradictions.

It is stunningly beautiful, frozen in time and evoking discordant nostalgic memories.

Its architecture is crumbling but also a unique hidden showcase of international Art Deco modernism.

The city represents perhaps the most concentrated and best preserved assemblage of Modernist architecture anywhere in the world. Since 2017 the entire city has been declared a

UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its outstanding architectural uniqueness.

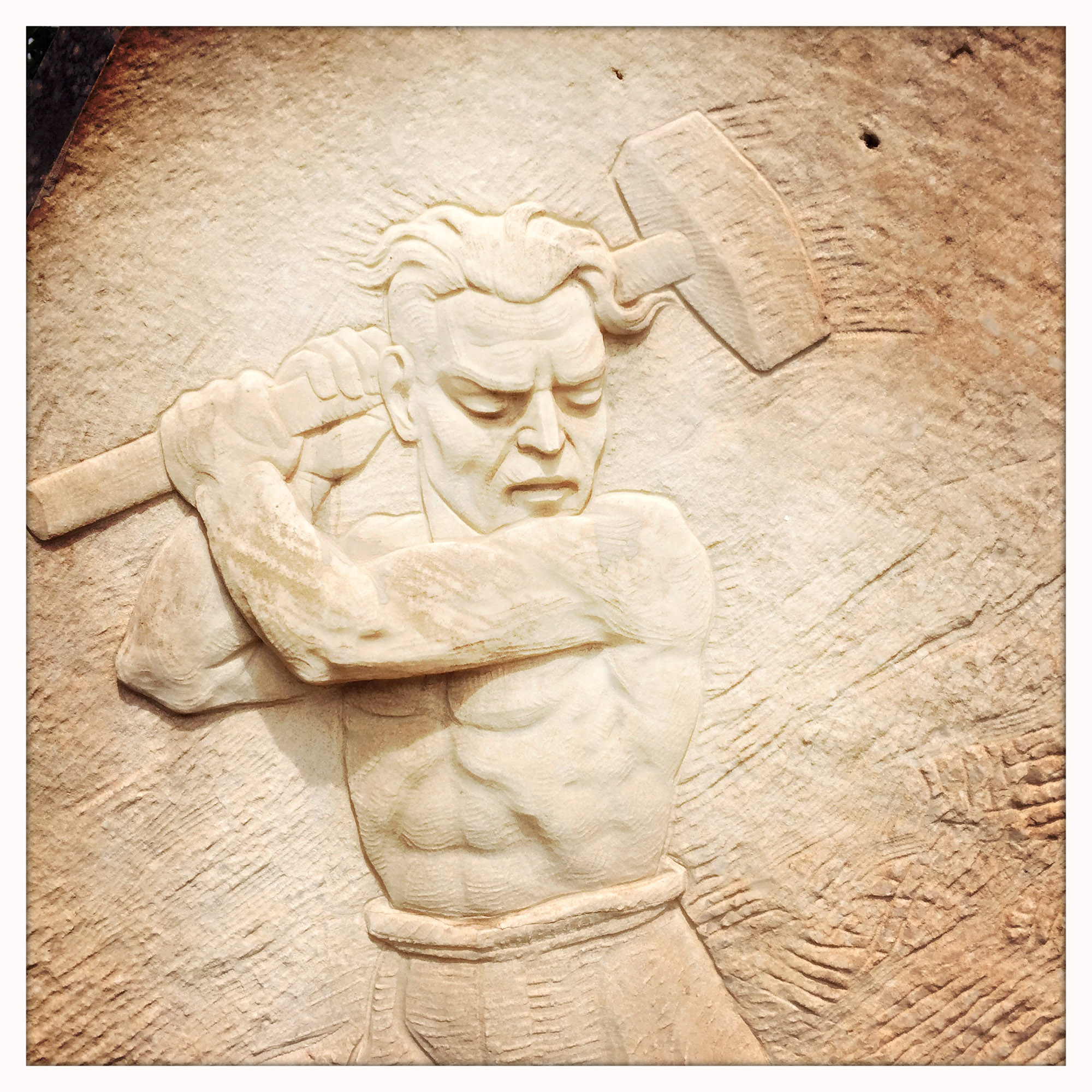

Under Italian occupation in the 1930s, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini briefly attempted to create an ‘Italian Empire’.

At that time, the palm lined Independence Avenue, than called Viale Mussolini, was completely off limits for locals.

In the boom years, between 1934-41, the European population of Asmara grew from 3,500 inhabitants in 1934 to 55,000 Europeans by 1940.

Inevitably the new inhabitants brought with them a European aesthetic and the architects and town planners were let loose on the diminutive African city.

Today, the legacy of these keen builders is still in evidence across the city. Over the course of its troubled history, which saw Eritrea engaged in a three-decade long independence struggle from Ethiopia, Asmara’s italianate capital remained largely untouched by modernisation and out of range of the conflict.

From the Expressionist Capitol Cinema to the Futurist FIAT station to the Rationalist geometry of the Ministry of Education, the city is a unique repository for early 20th century futurist architecture that continues to resonate and excite with its daring vision and daring architectural concepts.

The Capitol Cinema, opened as the Cinema Teatro Augustus in 1937 by architect Ruppert Saviele.

Fiat Tagliero Building, completed in 1938 by architect Giuseppe Pettazzi.

The Ministry of Education, formerly the Casa del Fascio, completed in 1940 by architect Bruno Sclafani.

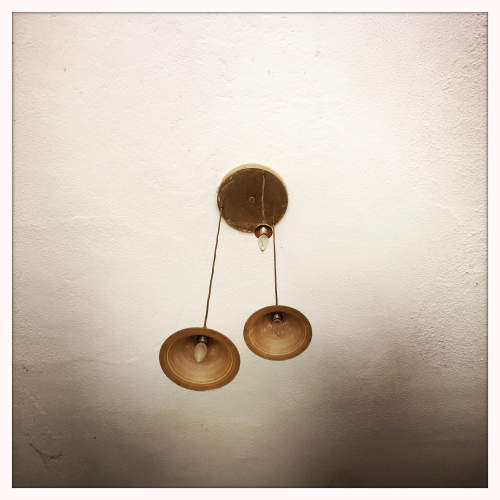

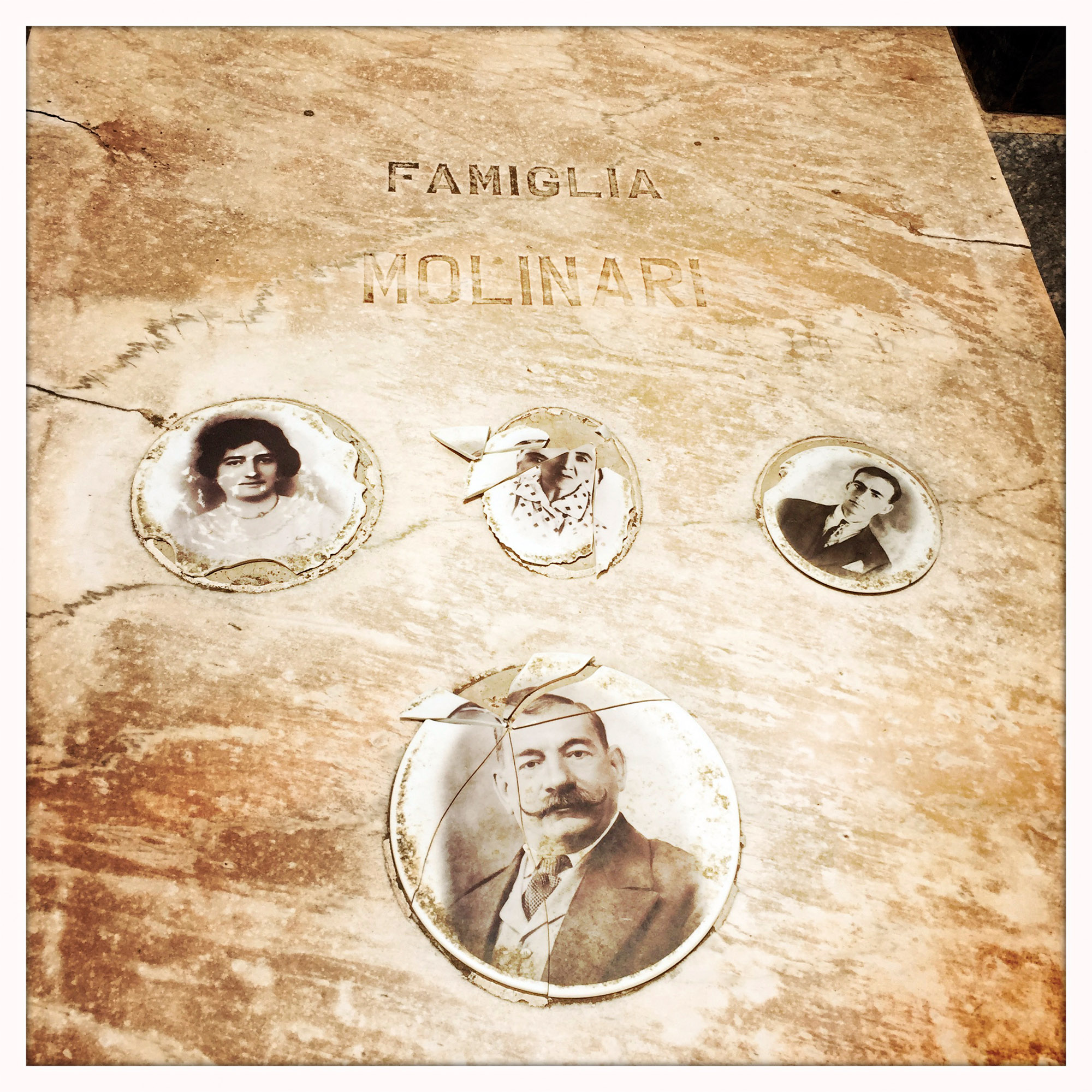

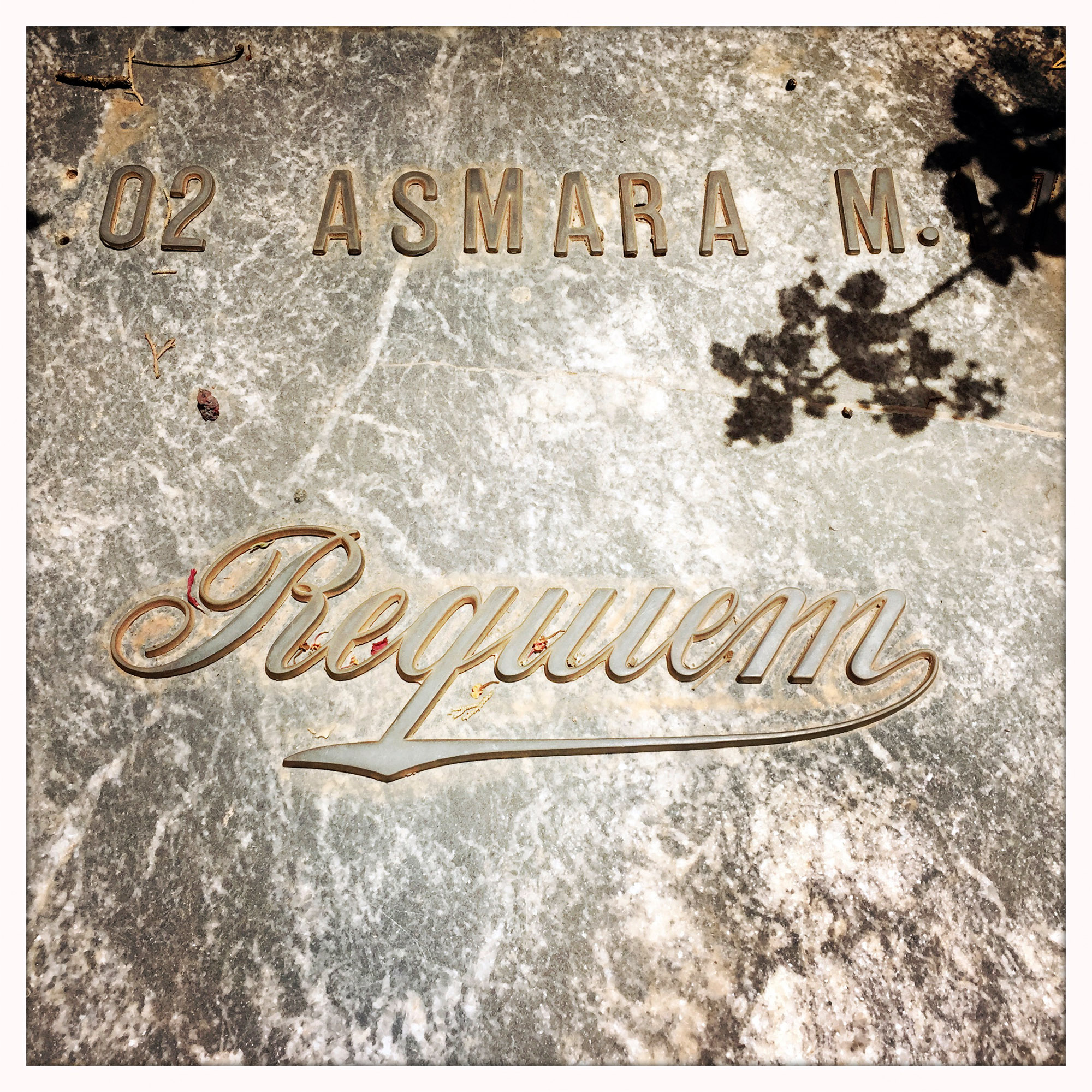

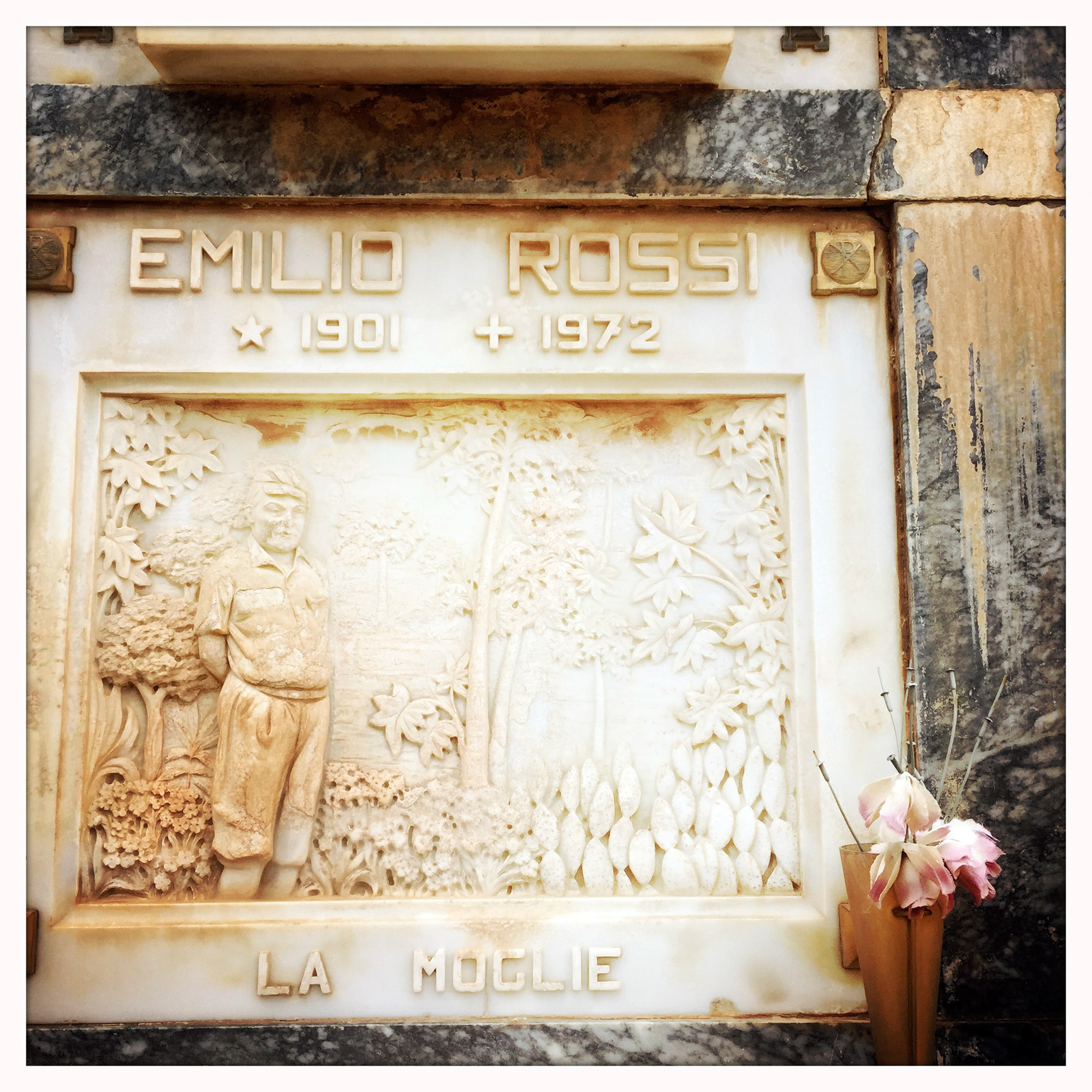

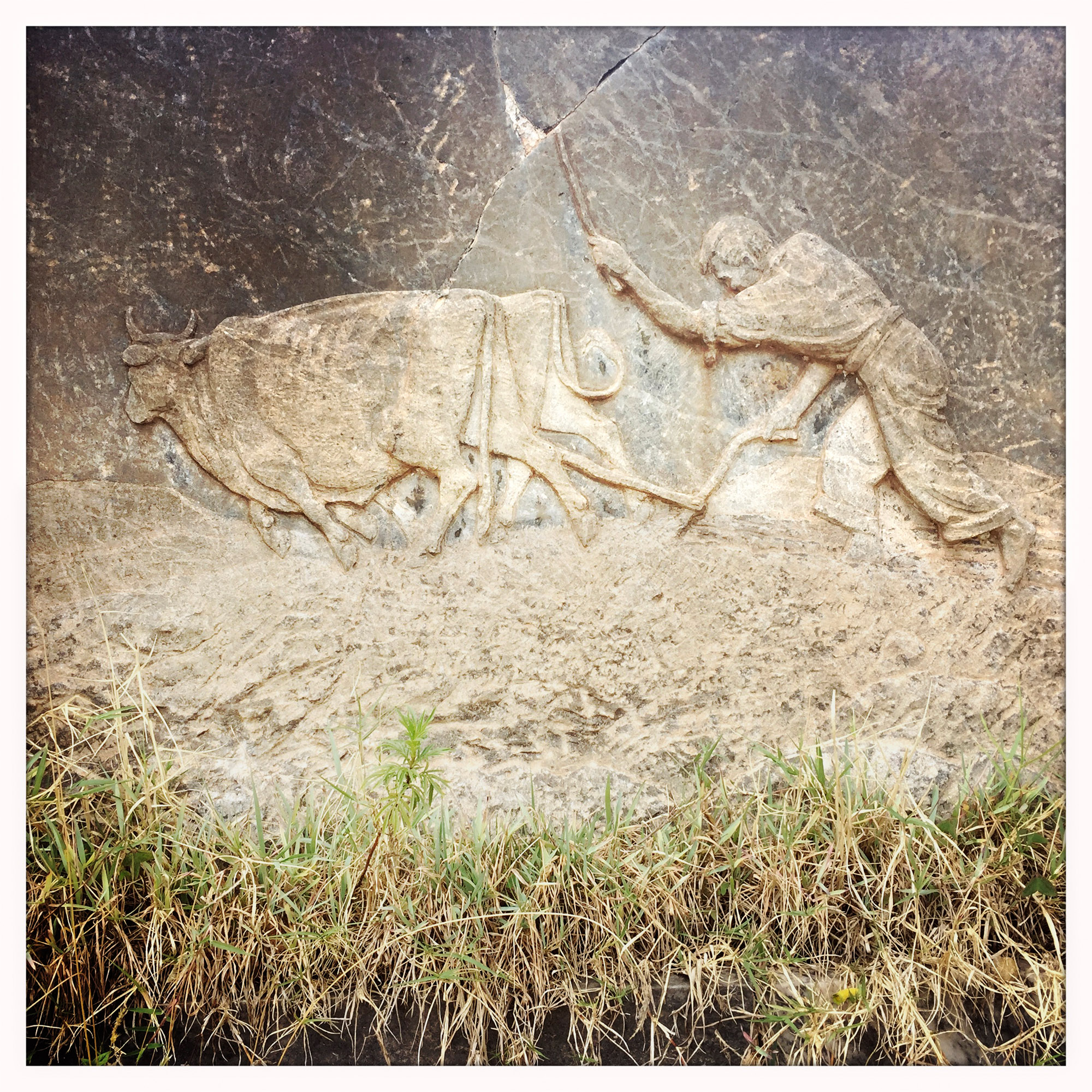

Stefan Boness has been fascinated by Asmara for over two decades and set out to explore the architectural gems in its city scape and the hidden history of this most unusual African city in old photographs and hints at the past in cafés and other public spaces …

… and cemeteries.

For this project, Stefan used the Hipstamatic app on an iPhone which offers a variety of ‘lenses’ and ‘films’, creating unexpected and unique Polaroid-style pictures.

An ordinary street scene turns into a dramatic impression of a place, full of atmosphere and fine details. The polaroid effect gives a pleasantly nostalgic touch to a city as rooted in its past as Asmara.

With a minimal amount of post-production, each image retains the element of surprise, taking the photographer back to an earlier time of film and experimentation.

Asmara is a virtual museum.

Medhane Teklemariam, project coordinator of the government’s Asmara Heritage Project