This is the story told over twenty years of how an African village escaped from poverty only to see its

progress reversed by climate change - a story that is being repeated across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

2005-2015 Mahamidu 'Banjo Boy' Charles (15) with the banjo he bought for the equivalent of GBP 0.50 . He writes and sings songs about various social issues. His family often run out of maze leaving Mahamidu to scour fields for any that have been dropped during harvesting. Right: 2015, 'Banjo Boy' is now 'Banjo Man' Mahamudi Charles (25) in the house of his parents.

The photographer Jan Banning and the writer Dick Wittenberg first visited Dickson village in Malawi in 2005 to document the reality of rural poverty - five years after the implementation of the Millenium Development Goals (Goal 1: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger). Through a series of portraits of more than forty families Banning wanted to show what is it like to live without a bed, without a waterproof house and to never know where the next meal will come from. They arrived just after a failed harvest which many expected would lead to starvation and death within the community.

The photos and text from the trip were published in the Dutch magazine M. Its readers, alarmed by the threat of impending famine, began donating money and over the next few years collecting over €140,000. Thanks to this help, the village slowly recovered. A school was built and within five years, the village could stand on its own.

2005-2015. Left: 2005, Saulos Fanuel (25), with daughter Ketilina (two) and son Lefiyamu (one), sitting on a bag of fertilizer. Saulos is the son of the village headman. Few people in the village eat meat as often as he does. Though he doesn't even have cattle or chickens. He prefers wild cat meat which he says is much better than chicken, goat or veal. He catches about five in a year. He wants to use their skins as decoration. Right: 2015, Saulos Fanuel (35), with three of their four children (L to R): Jolam (five) and daughters Dorin (less than one year) and Ketilina (11). The half bicycle is shared with a neighbour who owns the back wheel and the seat.

In 2015 - the target date for achieving the Millennium Development Goals - Banning and Wittenberg returned to Dickson. They observed that 'Dickson shows that escaping extreme poverty was possible. But slowly. Not without help form the outside. And not for everyone.' Residents now kept chickens, goats and pigs. A few had acquired an ox cart or a motorcycle and the wealthiest man owned a keyboard and a sound system. Banning's second series of portraits captured this unequal development.

In 2023 Malawi already experiencing the worst cholera outbreak in its history was hit by Cyclone Freddy devastating many regions in the country with extreme rains and flooding. A little over a year later Southern Africa began to suffer the worst drought in a century. Millions of people were facing acute food insecurity and malnutrition. The direct consequence of the climate crisis - Malawi, along with neighbouring Zambia, Zimbabwe and Namibia is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change and least able to adapt to its effects. Eight out of ten people in Malawi are small scale farmers completely reliant on the weather.

Hearing about the crop failures in Dickson caused by the 2024 drought Banning and Wittenberg returned to the village once again to see how the villagers were defending themselves against the consequences of climate change - a global phenomenon to which they had contributed almost nothing. They found a community directly impacted by climate change with nowhere to escape to. A few villagers still have money or enough sellable animals to survive the crop failure. Some may have a radio (important for weather forecasts), a mobile phone (for financial transactions) and a solar panel to charge them: but as Banning notes "these things can't substitute for food, after all, they cannot eat their possessions". This third series of portraits is the announcement of a disaster in the making, a story of progress undone by global warming.

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Zeneti Julias (41) left her abusive husband in 2005 after discovering she was his second wife. By 2015, Zeneti had remarried Halison Thomas (44) and had four children. She served as treasurer of a village women’s bank, which helped her buy a secondhand bicycle. In 2024, her eldest son, Mandalisa (see photo 2005, and on the right in photo 2025), is married and independent. Her other children (2024) are Kolofida (16), Gine (12), and Thomas (7). This year’s severe drought led to a meager harvest of 250 kilos of maize, down from 1750 in 2023, and a failed peanut crop. The maize only lasted until July. Husband Halison works as a day laborer, earning one euro per day, insufficient to cover expenses, forcing Kolofida to stay home from school. They hope to harvest maize from their winter garden, in a favorable location, in February. Zeneti reflects that life improved until this year (2024), with good harvests, a new house, a bicycle, and a solar-powered radio. They still have two pigs and two chickens for emergencies. “The future depends on God; we cannot control nature,” Zeneti says. “Farming is hard work with little reward.”

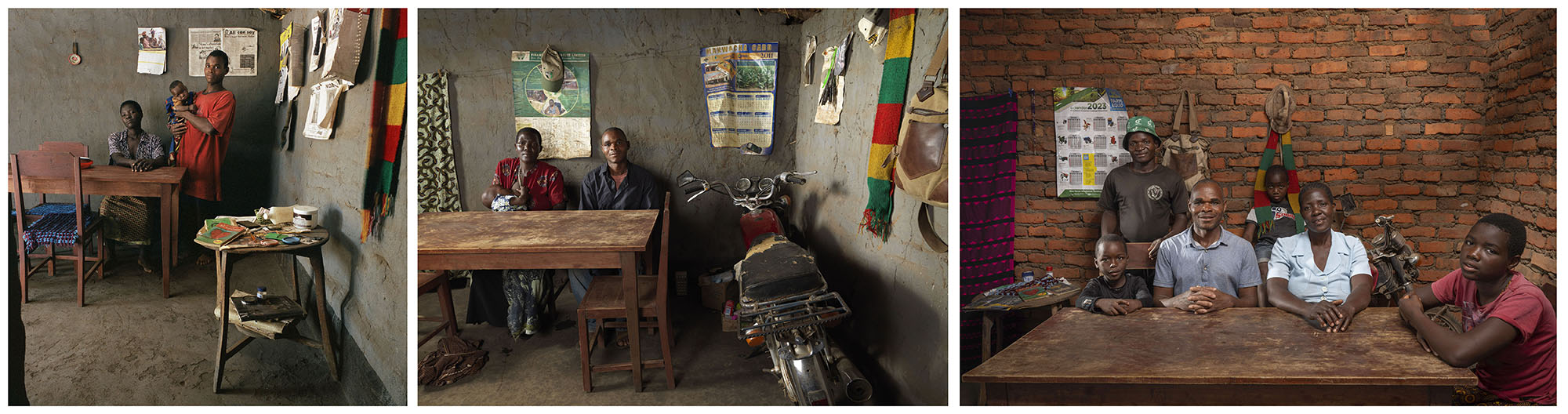

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Hammard Anderson (46) has long been the village’s wealthiest man. In 2005, he lived in a basic mud hut with a small radio but owned a maize granary, two tobacco sheds, livestock, and a bicycle. That year, he harvested five bales of tobacco (100 kg each). By 2015, Hammard leased land, harvested 100–200 bags of maize (5,000–10,000 kg), and produced 2,500 kg of tobacco annually. He invested in fertilizer, hired labor, and irrigated fields using his car and ox cart. He built a large brick house, bought a motorbike, a 1992 Mazda pickup, and owned seven cows. Between 2015 and 2024, Hammard's situation remained stable, but the 2024 harvest was very poor: some 3,000 kg of maize and 1,800 kg of tobacco, down sharply from 2023. He currently owns five cows, two goats, two pigs, and seven chickens, and rents two houses in Kasiya town for ten euros per month each. Hammard, one of the few in the village to finish secondary school, cites lack of cash and education as others’ main struggles. His biggest challenge is paying nearly 500 euro per semester for his daughter Charity’s nursing and midwifery studies at university. Besides that, his worries – as Dickson's wealthiest man – are limited, at least in the short run. In July 2024, his family moved into a four-room house. However, their TV is unusable due to inadequacy of solar power, and their 1992 pickup is awaiting repairs. We see him with his wife, Emelida (now 43) and, on the 2005 and 2015 photos, with their twins Precious and Priscilla, now 12. Their home prominently displays the 2015 photo.

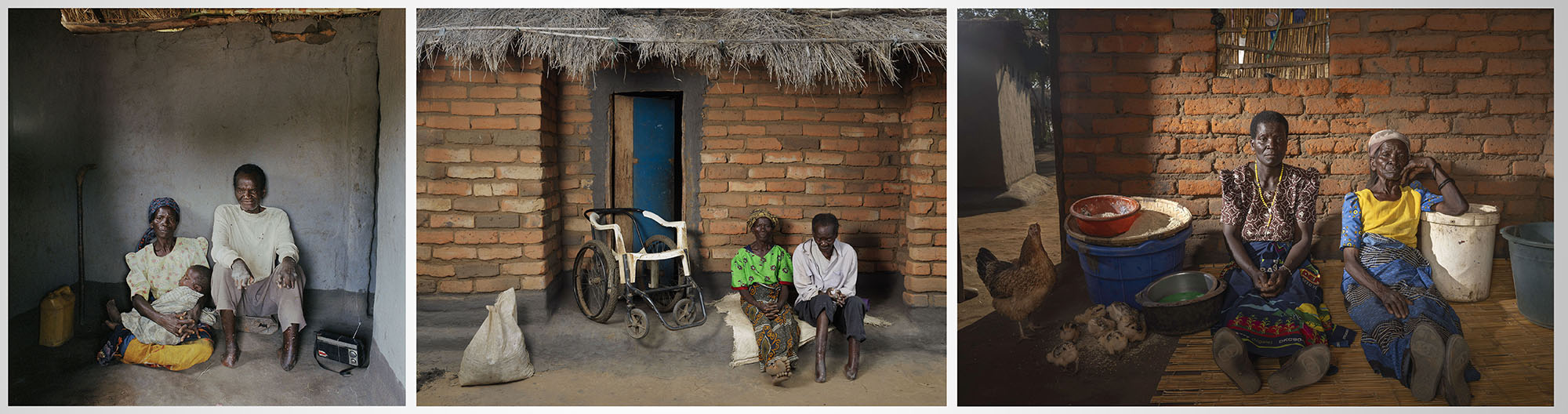

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Sesiria Erenesto, 84, is the village's oldest resident and among its most vulnerable. Widowed since 1995, she has lost six of her ten children. Despite her 38 grandchildren, who are also impoverished, she remains destitute and hungry. In 2024, her grandson harvested only 200 kilos of maize from her land, compared to 600 in normal years, with the drought leaving the crop underdeveloped. Living under a roof full of holes, she survives on maize husks, eating twice a day at most. Her future depends on a grandson’s day laborer job earning one euro a day, but if that ends, her situation will become very dire indeed.

Hopeson Thunde (55) with his wife Lusiya Kalichero stand in the main room in their house, where they keep their bicycle. He is one of three villagers who speak reasonable English. He still regrets every day that he was unable to continue his education due to lack of money. Aron, his second youngest son, has completed high school. (image taken in 2005)

Marigerita Rafael (65) buried 11 of her 15 children, one of whom died of AIDS. Her husband passed away during the famine three years ago and this year she has suffered a miserable harvest. (image taken 2005)

2005-2015-2024 Augustino Wilson, now 82 and the oldest man in the village, lost his wife, Keterina, in 2019. In the late 1990s, he lost a son and daughter-in-law to AIDS, and by 2005, he and Keterina were caring for three grandchildren (see 2005 photo). Four of their ten children had already passed away by then. In 1999, thieves stole their eight cows, wiping out their savings. Matters worsened in 2015 when Keterina developed tuberculosis, which drained their resources. They were also supporting three (other) grandchildren at that time. By 2024, the grandchildren from the 2015 photo now live with their mother. Augustino’s 2-acre field is tended by his children and grandchildren, especially Mariguerita (24, see 2024 photo; and second from the left in the 2015 photo), who, despite being divorced with three children, helps him. Augustino, now reliant on a cane, can only shuffle around. They survive on one or two meals a day, mostly maize husk porridge, leaving him among those at risk.

2005-2015-2024 Aron Thunde (born 1977) wanted to become a teacher after completing secondary school but was not accepted into the program. His conclusion: "I’ll become a successful farmer instead". In 2005, at 28 years old, he was already one of the most prosperous people in Dickson. Newly married, he had a relatively large house (by village standards) with furniture purchased from his tobacco earnings. The 2005 photo shows him with his wife, Lamesi (born 1984), and their newborn son, Bestar. By 2015, Aron had made further progress. He now owned five cows, an ox cart, a motorcycle, a radio, and, as one of the first in the village, a mobile phone. The baby in the 2015 photo is their youngest son, Ian (born 2014). In 2024, the family includes Aron’s brother, Thomas (born 1995), who lives with them, as well as their children: Vanesa (born 2010), Ian (born 2014, seen on the motorcycle), and Hopeson (born 2018). Their eldest son, Bestar, and daughter, Tadala (born 2007), now have families of their own. The furniture is the same as 20 years ago, and even the same booklet still sits on the coffee table. Aron is, alongside Hammard, one of the village’s most successful farmers. He has built a large, new seven-room house, though it remains unfinished due to the poor harvest. Whether it will be completed in the coming years is uncertain. Recovering from a failed harvest often takes multiple seasons—if recovery is even possible amid ongoing climate change. Aron works his six acres of land, plus three rented acres, entirely on his own, a demanding task. In 2024, he harvested only 48 bags of maize (2,400 kilograms), compared to 60 bags last year. Still, his losses are modest compared to others. The tobacco harvest, which in 2023 yielded 80 bales of 100 kilograms each (earning 125 euros per bale), has completely failed this year. His winter garden is entirely dried out, producing no vegetables at all. To afford fertiliser for the next planting season, he was forced to sell one of his five cows—leaving him with the same number of cows as in 2015. In addition to the four remaining cows, he has one goat, three pigs, and three chickens. “Everything is stagnating. If these kinds of droughts happen more often, farming has no future. But we’re stuck because it’s all we know. Nothing else.” Even moving to the city, without any connections there, feels like a hopeless prospect.

2005 A group portrait of the residents of Dickson village. To the left of the pump, standing, is the village headman; to the right of the pump, sitting, Anderson Isimu (65), maimed by leprosy since 1973, once the richest, now the poorest man in the village.

2005 Children play a game of football in Dickson

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Saulos Fanuel (40), the eldest son of longtime village chief Fanuel Saulos, is pictured with his wife, Fomiya Samalani (39). In 2024, as in 2015, they are photographed with their sons Lefiyamu (20, seen as a baby in photo #1), Jolam (15), and daughter Dorin (a baby in photo #2, now 10). Their eldest daughter, Ketelina (seen at age 2 in photo #1 and also in photo #2), is now married. The half bicycle visible in 2015 (shared with a neighbor, who owned the seat and rear wheel)—a valuable possession—was sold in 2024 to buy food. They own a 4-acre farm where they grow maize, tobacco, and peanuts. This year’s harvest was only 4 sacks of 50 kg of maize, which has already run out; they typically harvest about 40 sacks. They also harvested 100 kg of tobacco (down from the usual 300 kg; see drying leaves in photo #2), and their peanut crop completely failed. With no livestock to sell, they lack reserves. In 2005, he successfully hunted wildcats for meat and fur (for decoration), but these have since nearly disappeared. He views his economic position as having gradually improved from 2005 up to last year (2023), but the 2024 crop failure has erased this progress. He supports the family as a day laborer on an estate, earning Mkw 2,000 per day, though the job’s future is uncertain. The family currently survives on nzima (porridge) made from maize husks (see photo #3). In the locked chest are medications and medical records. Since 2023, Saulos has volunteered as an unpaid medical worker in Dickson, primarily monitoring children under five for malnutrition and growth delays (see scales and measuring tape in photo #3).

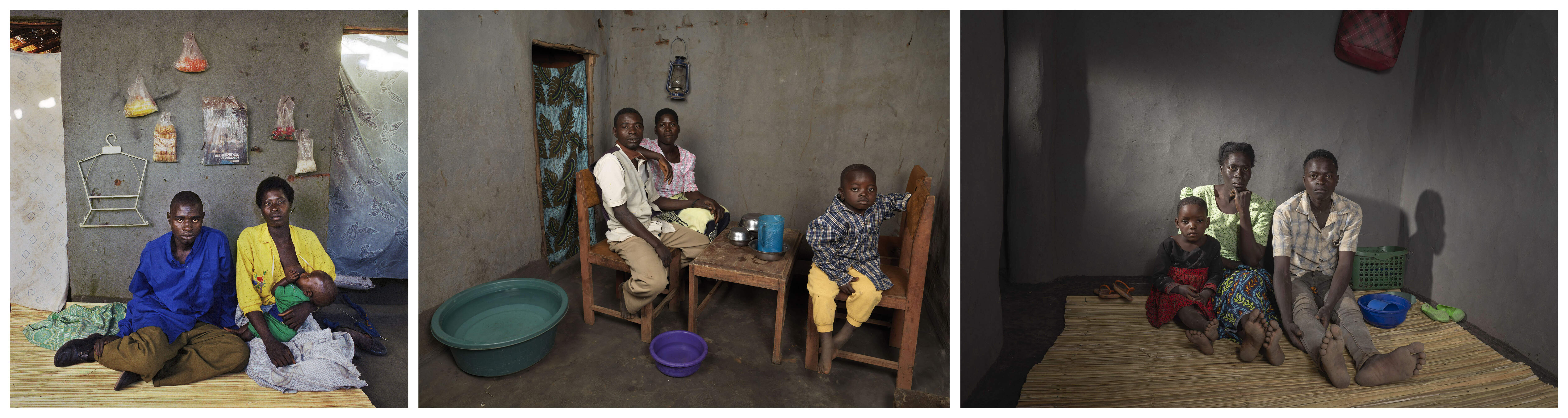

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Magdalena Bonifansio (born 1957) is shown in 2015 and 2024 with her husband, Dadi (born 1952). By 2005, three of their 11 children had died, and they were still caring for five, despite Dadi’s alcoholism. In good harvest years, they managed for nine months on maize porridge and vegetables; by 2015, their situation had barely improved. In the 2005 and 2015 photos, their youngest son, Chisimo, appears at age 3 (and later 13). Their grandson Chifuniro (born 2007), who moved in after his mother’s death, appears with them in the 2024 photo. By then, Dadi, debilitated by a stroke, could no longer work. Magdalena harvested just one 50-kilo sack of maize this year, down from 20–30 sacks in earlier years. Their children help with the land and share harvests when possible. Magdalena and Chifuniro together earn one euro daily as laborers, which barely meets their needs. They survive on maize husk porridge, eating twice a day if food is available. Till 2023 their situation had slightly improved, but worsening conditions in 2024 leave the family at high risk of severe hunger and starvation.

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Village chief for many years, Fanuel ‘Dickson’ Saulos (born 1944), was recently promoted (elected) to head of six villages, including Dickson. In the photos, he is seen with his wife, Dziko Gidala (approximately 65 years old). The chief is illiterate. Between 2005 and 2015, the couple's poor economic situation had somewhat improved, as evidenced by the purchase of a solar panel and a chair, along with the tobacco harvest (visible above their heads) and fresh vegetables and fruit – although the maize harvest in 2015 was also modest. These items – the solar panel and chair – have since worn out, and the couple now (Oct. 2024) has no money for replacements. They rely on others’ solar cells to charge their mobile phones (necessary for money transactions). On their 2.5-acre farm, they harvested only two sacks of maize (of 50 kilograms each) in 2024. They still have five chickens. Most of the field work is now done by a grandson. After this year’s crop failure, they feel threatened by starvation. The harvested maize is depleted, and they survive on maize husk porridge. The colorful bag contains clothing. In the bucket (left), we see maize husk flour (left). The children seen in the 2005 photo are now married and have left home.

2005 - 2015 - 2024 Livinese Henry (born 1978) and her husband Henry Simenti (born 1976) face extreme hardship. Their 2024 harvest yielded just two buckets of maize, barely 40 kg, which they harvested early due to hunger. Livinese works as a day laborer, but Simenti couldn’t find work due to competition. They have no animals, and their winter garden is dry. By mid-October, they couldn’t afford even one kilogram of maize, surviving on husks. Most days, they go to bed hungry, fearing malnutrition for their children. Their best years were 2013-2017, with stable weather and subsidized fertilizer, but those opportunities have since dwindled. Henry is infertile, but Livinese desperately wanted children and chose to conceive with other men. Their oldest child, Simenti (see photo 2005, and on the far right in the 2015 photo), has since passed away . The surviving five children are (in photo 2024), from left to right: son Akim (born 2007, on left in photo 2015); son Owen (born 2003, baby in photo 2005 and third from the left in photo 2015), daughter Chimwenwe (born 2010, the youngest in photo 2015), and the youngest twins from 2017, Tawina (the son in the middle) and Talandira (the daughter, second from the right).

2005-2015-2024 Left image from 2005. Anderson Isimu (65) with his wife Yosofina (58). He is the poorest man in Dickson. Long ago, he was the richest. He had a car. After him, nobody in the village managed that. In 1973 he contracted leprosy and had to stay in hospital for a year during which time thieves stole his possessions. Since then, he has mostly been stuck at home with his best friend, his radio. He was shunned by the other villagers, but recently, they repaired his roof. And on Sundays, they take him to church on a bicycle. Centre image from 2015. Anderson Isimu (75) with his wife Yosofina (68). outside their house with the wheelchair he uses to get around. Right image from 2024. Malieta Anderson, Anderson Isimu's daughter with her mother Yosafina. Her father died after 2015.

2005-2015-2024 Rice Nyangulu (45) and his wife Jenet (44) have five children. Together, they make a 50 kg bag of maize last for 21 days. In the market, it now (Oct. 2024) costs ± 20 euros. Their youngest child, Tawina (9), clearly eats less than the older children, Robert (20, already in photo 2005) and Callings (15). Their eldest son, Vickson and to left in photo 2005 and 2015), is married and no longer lives at home. In 2005, the family had some savings from tobacco sales, a bike, and livestock. By 2015, Rice had a successful tobacco harvest, four cows, and hired workers. However, their son Callings’ heart condition drained their finances, even though his heart surgery in the U.S was covered by an American NGO. In 2024, Rice’s 2-acre farm produced only 50 kg of maize and 25 kg of tobacco, due to drought and lack of fertilizer. He can no longer afford to rent additional land or buy fertilizer. Medical costs for Callings—ten euro per month for medication and 15 euro per transport—have worsened their financial situation. Callings, now in the highest grade of primary school, needs to go to secondary education as he is too weak for farming. That will add more financial strain next year due to school fees. Rice’s current situation is worse than in the hunger year 2001/2002, when two close relatives died from starvation. Now, in 2024, the family ran out of maize even earlier. He still has 2 cows, 1 pig, and 2 chickens left, which he could sell if necessary. He also works as a day laborer, but with more competition, it’s becoming harder. His family is mixing maize with husks to stretch their food, and Rice fears they may not survive the year. Rice’s inability to afford dry planting, due to the medical costs, has worsened his situation compared to people such as Hammar. He believes that if droughts and floods continue to increase, many farmers will perish. Moving to the city is not an option due to lack of connections.

2005-2015-2024 Matrida Rafael (born 1963) is the first wife of one of the prominent villagers, Arbart Katayika, who drinks heavily and neglects her. She has eight children (born between 1984 and 2002). Baby Emele, seen in the 2005 photo, has since passed away (as of October 2024). In a 2024 photo, Matrida is pictured with her youngest son, Andrew (22), who still lives with her and has completed high school. They are currently staying in a temporary hut while a new brick house is being constructed to replace the old one, which had deteriorated and begun leaking. Her husband left shortly after 2005 to live with his second wife. By 2015, Matrida seemed to be managing economically, partly due to growing tobacco as a cash crop, and even had a new brick house. Matrida’s farm is slightly larger than average, measuring 3 acres, where she currently grows maize, soybeans, and peanuts. She also maintains a half-acre winter garden for maize and vegetables. This year (2024), she harvested only five sacks of maize (50 kg each), a sharp drop from her usual yield of around 30 sacks. To afford additional food, she now works as a day laborer on a nearby estate, earning Mkw 1,500 per day. Though she currently survives on maize husks (visible in the white sacks in photo #3), she does not yet appear to be at immediate risk of starvation. To protect her maize, she keeps a cat to deter mice.

2005-2015-2024 Enifa Gostino (40), daughter of Augustino Wilson (Photo #21), is pictured in 2024 with her son Wizilamu (19), the sole survivor of her eight children, and Charity (5), her niece. Since 2005, her life has been “a mixed bag,” marked by challenges like her divorce from Dryson Bulaimu (see photos from 2005 and 2015). Stable until last year, the 2024 crop failure has left her struggling to survive. Her one-acre field yielded just 100 kilos of maize, down from the usual 650-750. Her garden produced another half a bag (25 kg) instead of the typical five to six (250-300 kg), alongside small amounts of pumpkin and mustard leaves. With no external help, her only assets are two goats worth ± 35 euros each. Growing tobacco, the main cash crop, is financially out of reach. All of the maize she harvested have already been consumed. Enifa now works as a day laborer on a nearby estate, earning about a euro per day, which she and her son depend on. Recently, at the market, she found she could only afford maize husks, so they now eat maize porridge made from husks twice a day or less.