Internet cafes have been around in Japan for almost two decades but recently some have started to offer tiny, private booths, showers, laundry service and storage space reasonably priced for overnight guests.

Fumiya

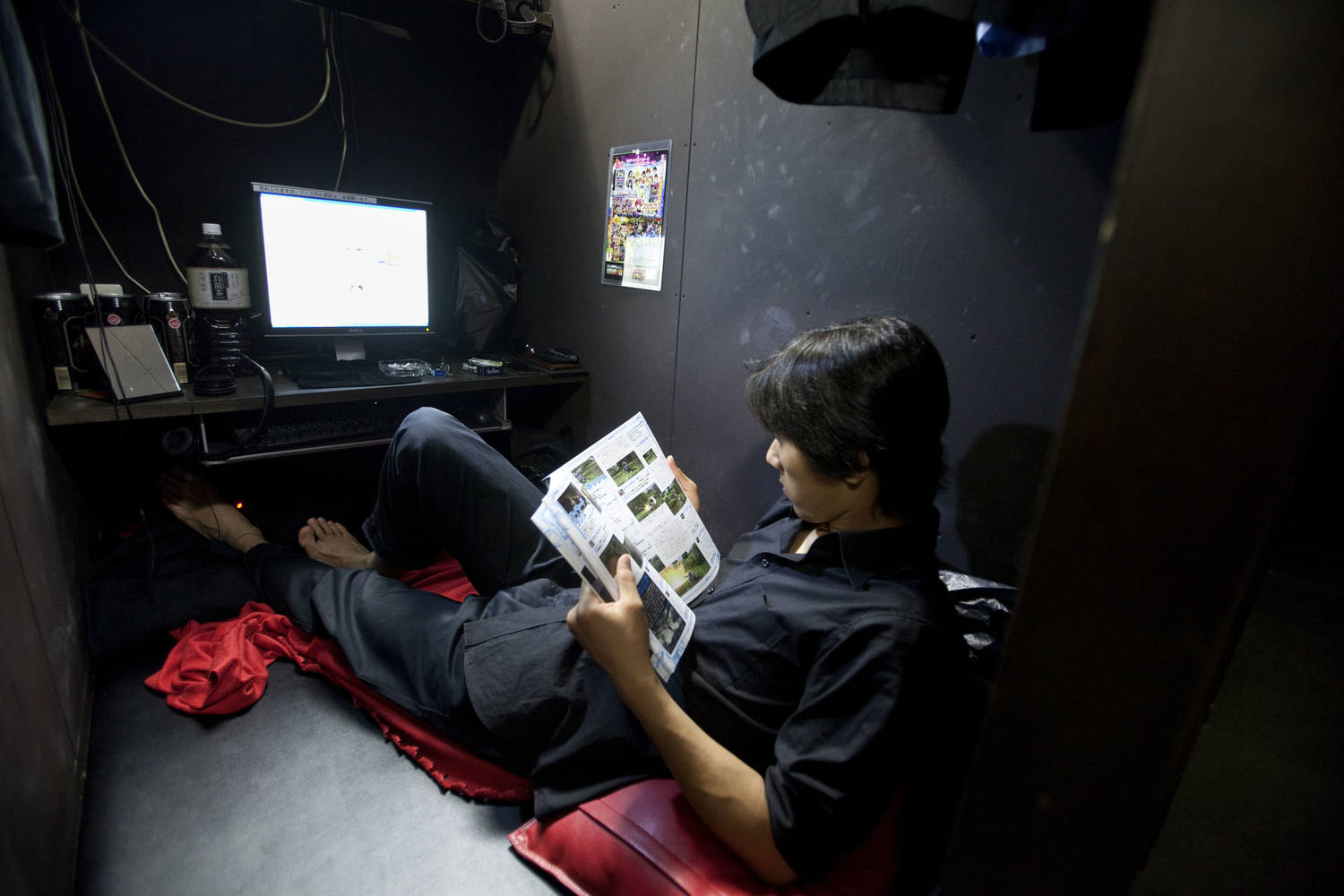

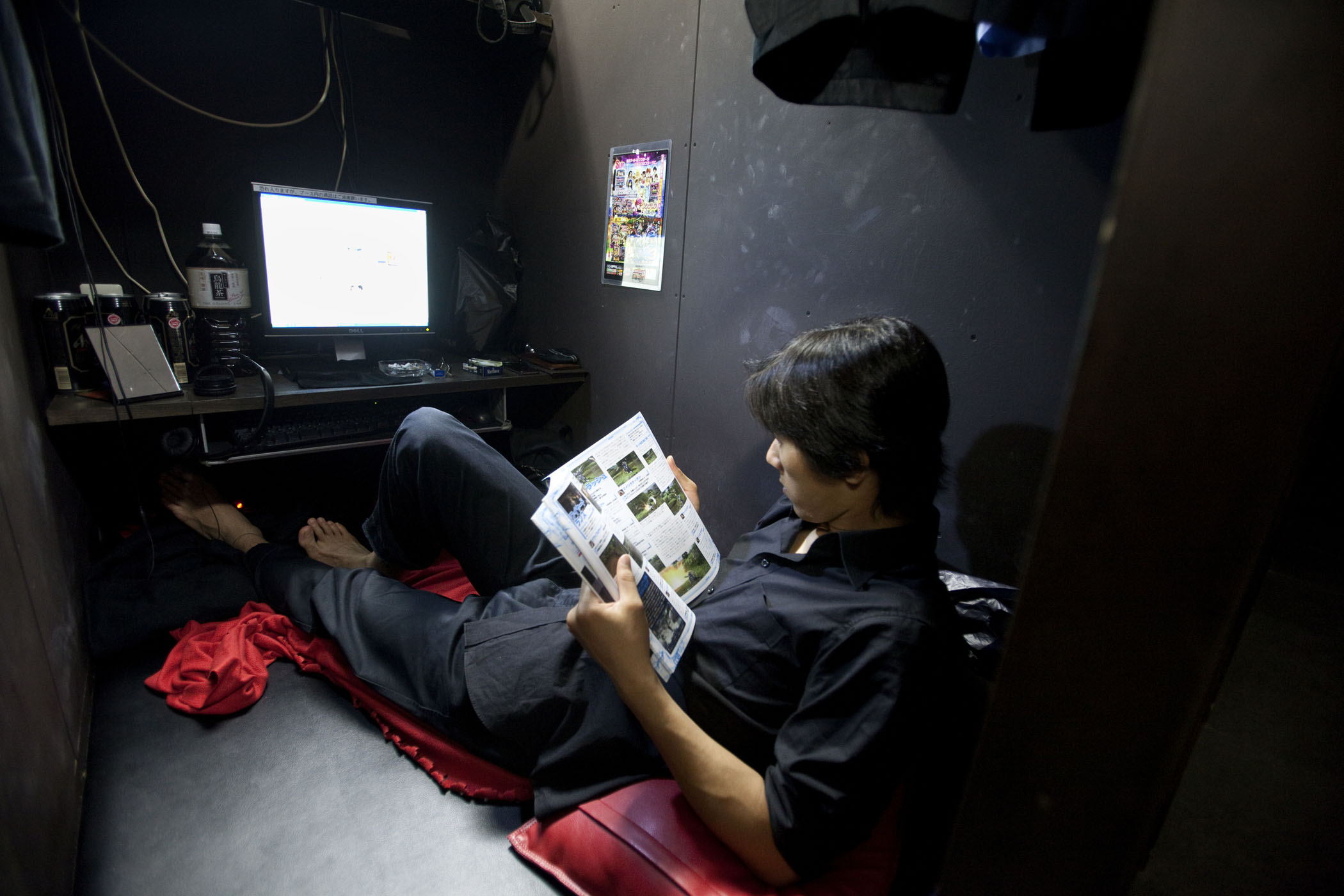

The first time Fumiya, 26, spent a night at the internet cafe, other people’s snoring and footsteps kept him awake throughout the night. Since that sleepless night, ten months have passed and the little noises don’t bother him anymore. Once he got used to sleeping with a blanket over his face to block out the fluorescent lights that stay on through the night, he says living in an internet cafe is “not so bad.” Fumiya started living at an internet cafe after he left his job with a dormitory. He looked for an apartment but it was more than he could afford. At first he rented a private booth for 12 hours just to sleep but soon realised that he could actually live there. Fumiya’s discounted monthly package costs 1,920 yen (US$25) a day, or around $750 a month. It’s cheaper than renting an apartment since he doesn’t have to pay for utilities.

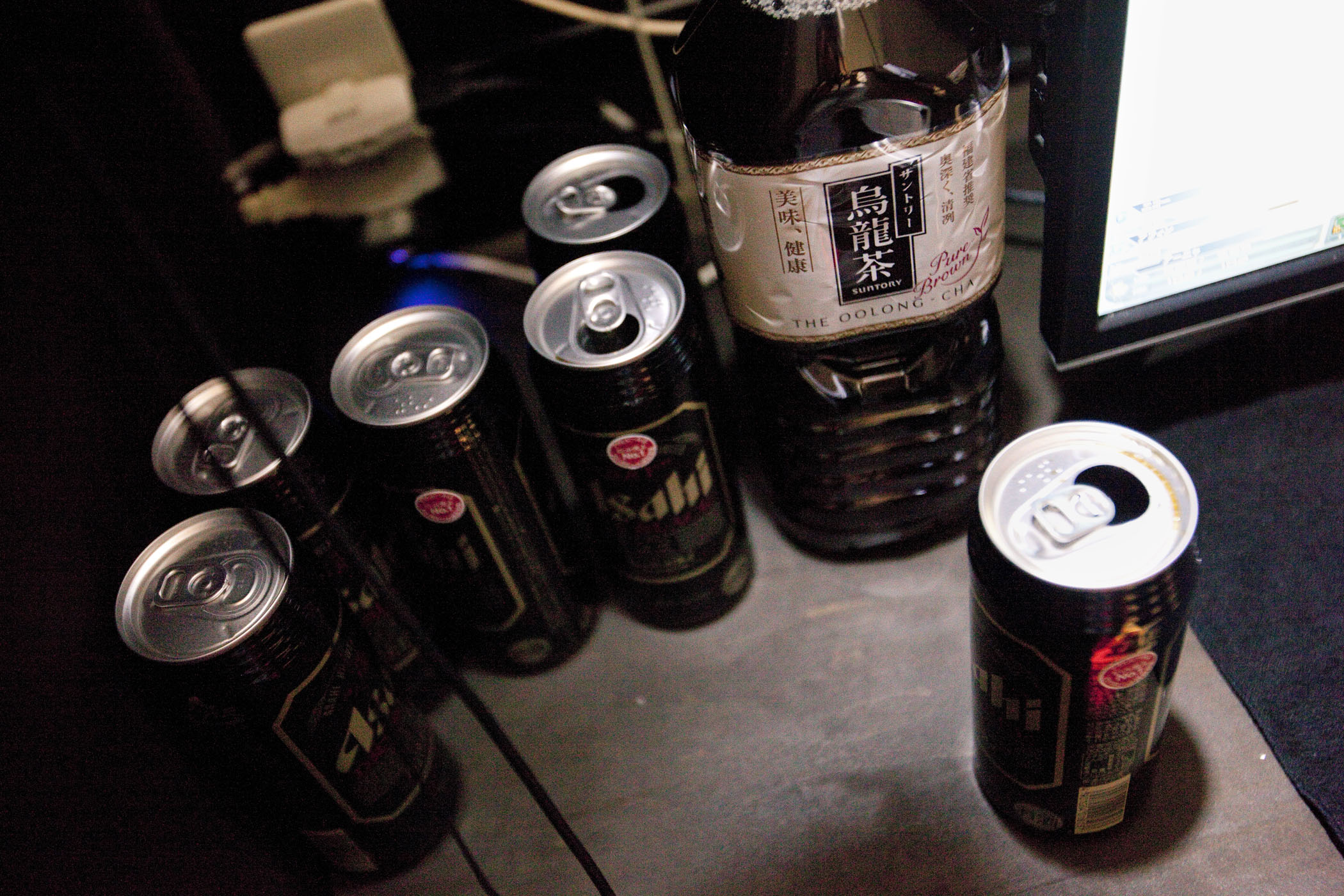

The booth is clean and the café offers unlimited free soft drinks, blankets and cushions. The booth is partitioned by 1.8 metre high dividers and a door and Fumiya can enjoy his bath-tub sized privacy of a 1.8 x 1.2 metre space which is big enough to sleep without bending his knees.

He currently works 8 hours a day, 6 days a week as a security guard and makes about 230,000 yen (US $2,900) a month. He says he needs about one million yen ($13,000) to pay for security deposits, estate agent fees and furniture for an apartment in Tokyo, money he can ill afford on his salary. He reckons it would take him up to five years to save up this much money.

“We need places like internet cafes. Without them, there would be many more people who have jobs but no homes.”

Fumiya eventually wants to be a regular worker so that he can have stability and rent an apartment. The older he gets, the more difficult life as an irregular worker becomes and the gap between the wages of those with full time contracts and casual workers is widening. By the time he reaches the age of 45, he will earn less than half of what people on regular contracts will make. “I want to get married and have a family. That is, if I’m lucky.”

According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2007 there were 60,900 people who were sleeping at in internet cafe on any given day. Around 5,400 people were actually living in the cafes because they had no other homes. Out of these long-term residents, 2,200 were unemployed and 2,700 were irregular workers like Fumiya. Japanese media has started to call them “internet cafe refugees” drawing attention to the plight of irregular workers whose salary is not enough to pay for their own apartment.

The number of low-paid workers on temporary contracts with no job security has been climbing steadily. In 1990, 20% of the workforce were temporary workers. By 2011 the figure had climbed to 35% according to a survey by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. A third of male workers and half of female workers on temporary contacts earned less than the government poverty line of 1.12 million yen (US$14,300) a year.

Tadayuki Sakai

Tadayuki Sakai, 42, smiles broadly when he recalls the time when he handed in his resignation to his boss. He worked for a credit card company as a regular worker, or ‘salaryman’, for 20 years. “I felt so good! So so good!”

It was a complete leap of faith for Mr Sakai as these stable, full-time position are becoming increasingly hard to come by in today’s Japan, where more than one in three people are employed as irregular workers.

After Mr Sakai quit his salaryman position, he moved to an internet cafe where he now works as telephone operator and temps for a friend’s computer systems company. Even though living in a bath tub-sized booth is his new reality, Mr. Sakai swears he is much happier now.

“I never ever want to become a salaryman again.”

Since the 1990s, Japanese companies have gone through painful changes in order to maintain their productivity and remain competitive. Workers used to be able to rely on secure, lifelong employment in return for unquestioning dedication to the company. Increasingly temporary contracts have come to replace secure ones and workers are expected to put in ever more overtime for fear of losing their jobs. Mr Sakai used to put in almost 200 hours of overtime at least three or four months of the year. “I didn’t have time to go home. I took short naps in the office and then went back to work when I woke up” he says. Yet when the company physician told him to work less after Mr Sakai showed signs of depression his boss started a rumour that he was ‘a psycho’ and a weakling.

Bullying and harassment such as being slapped or yelled at were routine in his company. “It’s a part of the older generation’s culture” Mr Sakai says with a shrug. He remembers that his boss once completely blanked him for a month after he turned down an invitation to have a drink. Instead of offering him early retirement or redundancy, though, he was slowly demoted from his executive position where he made 500,000 yen ( $ 6,400 ) a month first to an admin position and finally to debt collecting, for which he was paid 200,000 ( $ 2,550 ). “You keep getting demoted or given marginal positions until you feel compelled to resign. It’s really hard to keep one’s place.”

“You keep getting demoted or given marginal positions until you feel compelled to resign. It’s really hard to keep one’s place.”

When he is ready to leave the internet cafe Mr Sakai isn’t going to look for an apartment in Tokyo. He has lost hope in Japan and Japanese corporate culture and wants to move abroad. He neatly organises his belongings in his booth: one pair of black leather shoes, two dress shirts, one tie, one grey suit, a backpack and a briefcase.

“I have nothing to lose anymore. I don’t need to hold on to Japan. All I can count on is myself.”