The 620 million Africans without access to electricity cannot and should not have to wait any longer

Kofi Annan

More than 620 million Africans, or two thirds of the population of the continent, have no access to electricity. Whilst 99 % of North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and Egypt) are electrified, only 32 % of the countries south of the Sahara are. In the 48 sub-Saharan countries the total power capacity is 68 gigawatts while France alone produces 130 gigawatts.

Due to this lack of capacity, poor infrastructure and gaps in the power grid, the annual GDP of Africa is probably three to four percentage points lower than it could be. And this deficit makes economic development almost impossible- or at least slows it down – impacting school education as well as vocational training. In nine African countries more than 80 % of primary schools are not connected to the grid.

Benin, all 11.000 inhabitants of Gbekandji village are off the electricity grid and by eight at night the streets are empty.

Benin, Allonkpon. A child lights his way using a torch in this village of 2500 people without access to the electricity grid.

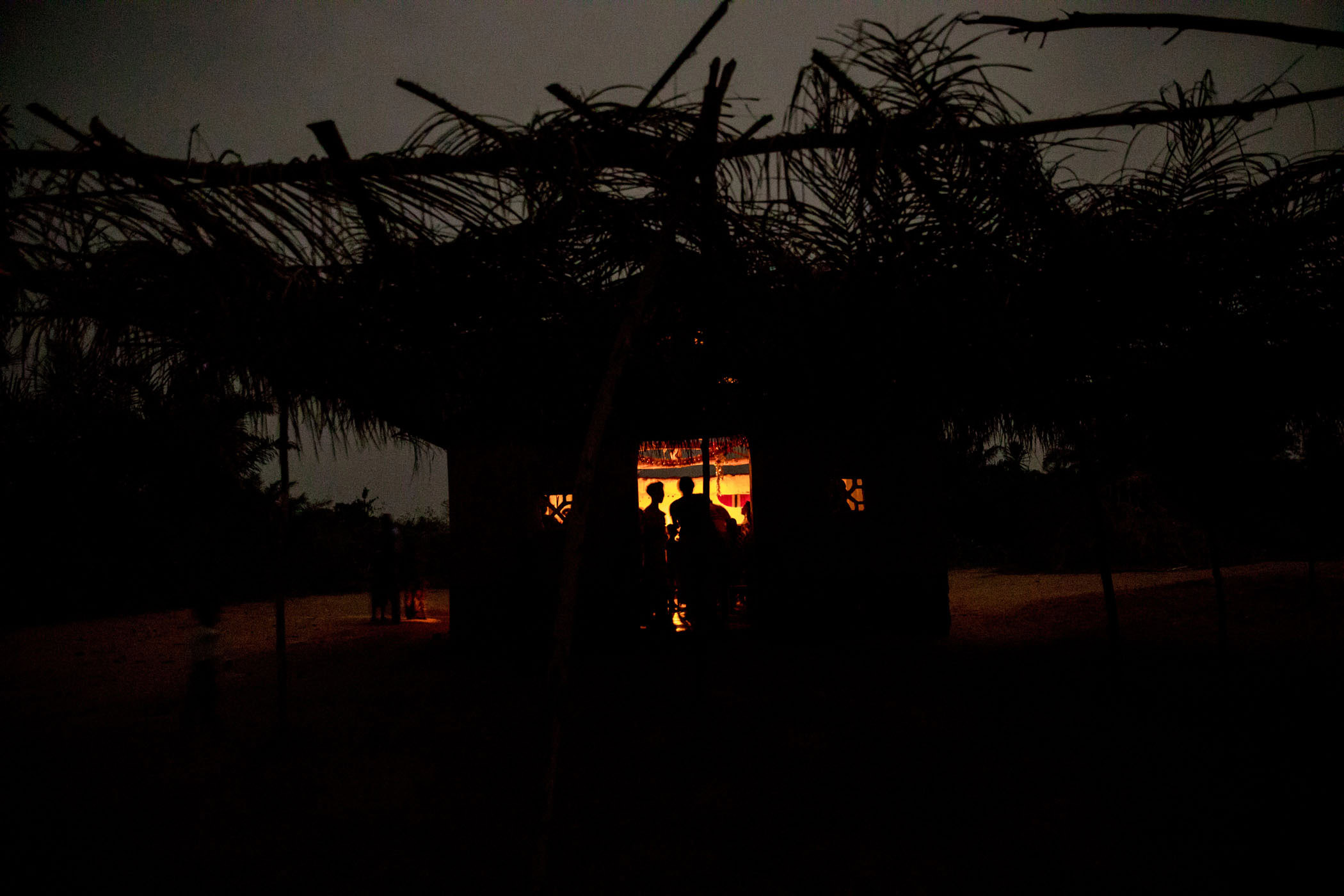

Benin, Kokahoue market, illuminated by candle light, takes place each night beneath a palavar tree. It is one of nine nearby villages that are off the electricity grid.

Benin, Glo night market lit by oil lamps in this village with no access to the electrical grid.

Benin, Seahovo village. Women selling food at night using oil lamps to light their goods. The village is not connected to the electrical grid.

Benin, Kokahoue. A market, illuminated by candle light, that takes place each night beneath a palavar tree. It is one of nine nearby villages that are off the electricity grid.

Benin, Kokahoue. A market, illuminated by candle light, that takes place each night beneath a palavar tree. It is one of nine nearby villages that are off the electricity grid.

Benin, Fantou, Nr. Cotonou. Food stalls and a small shop lit by oil lamps in a village that is just 45 minutes from the Presidential Palace but not connected to the electricity grid.

Benin, Attankpe, nr. Allankpon. A woman uses a torch and an oil lamp to illuminate the room as midwife Raïssa Godjo helps Dossou Mariette give birth in a village that is off the electricity grid.

Benin, Allankpon. A rural health centre that is off the electricity grid and illuminated by oil lamps.

Benin, Attankpe, nr. Allankpon. Midwife, Raïssa Godjo, illuminated by candle light, helps Dossou Mariette give birth in a village that is not connected to the electricity grid.

Benin, Seahovo. Children sleep in a room lit by candle light in a village that is not connected to the electricity grid.

Benin, Allankpon. A evangelical church service in the village of Atankpe Aligodo. The small village is not connected to the electricity grid.

Benin, Allankpon. A evangelical church service in the village of Atankpe Aligodo. The small village is not connected to the electricity grid.

Benin, Allankpon. A family work by candle light to process palm oil. The lack of electricity limits the family's ability to work and reduces their potential income.

Benin, Seahovo. The villagers prepare soap with palm oil and soda using an oil lamp to light their work in a village that is off the electricity grid.

Benin, Agbangnizoun, Abomey. A woman breastfeeds a baby while running her food stall, which is lit by an oil lamp.

In Benin, well-lit areas are only a few kilometres away from areas steeped in complete darkness. The village of Fanto with its 665 inhabitants is only ten minutes from the National Road No 2 connecting Cotonou with the north of the country. This 10 minute journey is a quick time-travel several decades into the past; from the tarmaced road with a power line running alongside it to scrublands of manioc, sweetcorn and sugarcane fields stretching out into the distance. A cable leads from the road to a brightly-lit Catholic church in which the faithful attend evening mass. Behind the church the village lies in complete darkness except for the stalls of the evening market arranged around a little square which are lit by a dozen paraffin lamps.

Benin’s urban population enjoys more comforts but doesn’t always have electricity either. The supply is cut off several times a day in order to avoid overloading the grid and sometimes there are complete blackouts as on April 9, 2016 when in the entire country was without power. This constant uncertainty impacts on daily life. Retail businesses, workshops, hospitals and offices are equipped with generators to protect them from blackouts. This is why everywhere – on pavements and roadsides – bottles of fuel, smuggled from neighbouring Nigeria, are offered for sale. These stalls, which often get shut down by the authorities, are easy to spot: wooden shelves with lines of carboys. In the dark, the green neon light turns these makeshift counters into a scene from a science fiction film.

In a report of the African Progress Panel (APP) from 2017 the late UN General Secretary Kofi Annan, who was born in Ghana, warned in his foreword: “The 620 million Africans without access to electricity cannot and should not have to wait any longer.” It’s true that the governments of some countries, aided by international organisations and with the assistance of foreign countries, have already taken appropriate action which has got another 140 million Africans connected since the beginning of the century. Yet this improvement is lagging behind the demographic growth. According to the APP report, the number of people without access to electricity may even increase by 45 million by 2030. “Africa needs to be electrified more quickly,” demands Annan.

Benin, Porto Novo. A woman selling contraband fuel by the side of a road. These traders are nicknamed 'Al Qaeda' due to their habit of exploding.

Power generation in Africa is plagued by a number of problems. A lack of initial capital to build the infrastructure, a population that often doesn’t pay electricity bills, a lack of maintenance of existing power stations, the cost of installing a grid over long distances and, as ever, corruption. These problems are also manifest in Benin. The key figures of Benin’s power generation are very disappointing. To compensate the state rents an enormous number of generators at extortionate

prices and runs these at a cost of 500 million West African Francs (over EUR 760 000) of fuel per week. In the Akpakpa power station on the edge of Cotonou 32 megawatts are unused. The plant has not generated a single kilowatt since 2010. The helpless-looking director Fortuné Soude says that the maintenance work was interrupted during a tender. “This is totally incomprehensible,” an engineer says excitedly. “Everything was stopped in order to make public affairs transparent.

But all the bids were sincere and beyond doubt.” Soude suspects an ‘intrigue’. In the courtyard of the power station fifteen brand new generators are humming away behind a fence. They supply Cotonou with electricity. “A state within a state!” grumbles Soude. And a lucrative business for private firms which are in with the ministries.

Benin, Porto Novo. Unregulated electrical power lines connecting to the power grid.

Somalia, Mogadishu. A man prays in the decrepit electrical control room in the Sahafi Hotel.

Chad, Kinesserom. Mobile phones charging at a booth that uses a generator to power its service.

In order to drive power supply in Africa forward, development experts are relying more and more on renewable energy sources. These are easier and cheaper to construct and make operational. Thanks to such innovations and regional power grids the African continent could leave its shadowy existence behind.

The African Progress Panel (APP) in their 2017 report predicted that less than a third of the 315 million Africans who might have access to a power by 2040 will be connected to traditional national grids. The overwhelming majority will get electricity from their home solar panels or regional power plants feeding a micro grid.

Benin, Allankpon. A solar powered street light illuminates people selling food from roadside stalls.

Benin, Bekandji. René Justin Danssou helps children study at night, reading by the light of a Chinese made solar powered lamp that cost 25,000 CFA (GBP 34.00). The village, of 11,000 people, has no access to the electricity grid.

Senegal, Seleky. A family watch the television at their home where the power is supplied from a photovoltaic solar array.

Senegal, Selecky. Women socialise beneath a solar powered street lamp.

Benin, Cotonou. A busy bridge is illuminated by solar powered street lamps.

Ethiopia, Ashegoda, Mekele. A woman watches over cattle grazing near the wind turbines of the Ashegoda wind farm.

Senegal. Bokhol solar power plant where 75600 solar panels cover 35 hectares producing 20 MW, the largest in West Africa.

Kenya. A giraffe walks across a road near Olkaria geothermal energy plant in Hells Gate National Park near Lake Naivasha, Africa's largest geothermal project.

Senegal, Niomoune. Elie Paul Dieme repairs a solar powered street lamp.

Senegal, Selecky. Solar lights illuminate a house and the surrounding trees.

Words based on a text by Jean-Marc Gonin. A full text is available on request.