Mammals were non existent in New Zealand until the arrival of humans. They brought with them a deadly cargo of invasive species resulting in the extinction of nearly half of all the country's bird species including some of the only flightless songbirds to have ever existed. Today New Zealand has the highest proportion of threatened indigenous species in the world.

“Every New Zealand habitat is under siege”

Colin Meurk, University of Canterbury ecologist

In order to protect their remaining indigenous birds New Zealand has targeted the invasive predators with a policy of total eradication - dubbed "the world's most ambitious conservation project attempted anywhere in the world". It has been likened to the exploration of space, the country's moon-shot, and has so far been estimated to cost more than six billion dollars.

The aim of the project is to eradicate all major predators by 2050 – specifically stoats, ferrets, weasels, possums and three different types of rats. The challenge is daunting and conservationists agree that current methods will not be sufficient to meet the target date and may not ever be possible. To attempt to do so ecologists, biologists, trapmakers, ethicists and engineers are coming together to rethink how to they the plan might be achieved while accelerating the pace of innovation.

Field specialists from The Capital Kiwi Project inspect kiwi recently released into the hills around Wellington, the capital of New Zealand. Kiwi have not roamed these hills for many generations. After the laying of 4,561 traps over 23,455 hectares, and years of work, on 19 November 2022, 11 kiwi were released into the wild on the south coast of Wellington. These inspections are the first since their release.

The Kiwi epitomizes the vulnerability of the indigenous population. In a mammal free environment it never had to develop a means of escape from predators. This all changed with the arrival of the Maoris who brought the kiore rat with them. Things got only worse with the arrival of the Europeans bringing with them black and brown rats.

Other more intentional animal introductions went very badly wrong. In an all too familiar pattern one invasive species was introduced to try and control

another. In this case the colonial settlers attempted to control the spread of rabbits – originally brought to New Zealand for food and sport – by introducing ferrets, weasels and stoats. They had virtually no impact on the rabbit population preferring the native birds were much easier to catch and had no defences against them.

The last and possibly most destructive introduction came with an initiative to establish a fur industry in the country by importing Australian brushtail possums who very quickly

escaped captivity and spread throughout the country. By the 1980s there were estimated to be more than 50 million possums in the wild consuming 23,000 tons of vegetation every night together with birds, their eggs , snails and other invertberates.

The combined impact of these invaders is hard to comprehend. 25 million chicks and eggs of native birds are thought to be consumed every year and 95% of kiwis born where stoats are present fail to make it to adulthood.

Laughing Owl (last seen: 1914)

Hatton’s Rail or Mātirakahu (last seen: 1893)

Bush Wren or Mātuhi (last seen: 1972)

Huia (last seen: 1920s)

South Island Kōkako (last seen: 1967)

New Zealand Little Bittern (last seen: 1890s)

New Zealand Black stilt (critically endangered)

South Island Piopio (last seen: 1905)

Auckland Island Merganser (last seen: 1902)

This bushtail possum was caught in a leghold trap, a non lethal device oftne used in the fur trade that must be checked daily. To achieve Predator Free 2050 campaign goals, the nation is deploying automated kill traps.

The first attempt at eradication began 65 years ago on one of the country’s many small islands, using traps and rodent baits dropped from aircraft. This effort was successful and following on from this over 300 New Zealand islands are now predator free.

The challenge on the NZ mainland is altogether different . To rid the four mile square peninsula of Miramar in Wellington of rats, stoats and weasels took four years, the installation of 11,000 baiting stations and the assistance of 1000 local residents. Other eradication initiatives have also achieved success but the area cleared so far is less than half a percent of the country’s total landmass. If they are to get anywhere near their goal the top priority is to dramatically reduce the

time spent servicing killing devices in the field according to Dan Tompkins, science director of Predator Free 2050 Ltd. Self resetting traps with dispensers to automatically bait them is one way to achieve this. They operate autonomously for months while feeding back data on the catch so staff are able to contiuously monitor activity and predator numbers. These traps are being rolled out across the country.

In the Southern Lakes region of the South Island Paul Kavanagh, project director for a consortium supporting volunteer groups estimates self-resetting traps are 49 times more effective than traditional devices. “our traps have been catching two to six possums per night, and we might not need to check the trap more than once

every six months.” Contrast this to a single-set trap which might make one kill and then be out of action for anything up to a month before a volunteer resets it.

New Zealand is now on the brink of being able to automate the mass killing of animals on a previously unimaginable scale. However it is questionable whether the ethical implications have been fully addressed. The use of poisons causes slow agonizing deaths. “As I read more and more about this plan, I became increasingly concerned” wrote the conservationist Jane Goodall in her ethical review of the eradication programmes. Others argue that the harm inflicted by predators on the native species far outweighs the harm inflicted in managing them.

Te Manahuna Aoraki Project was created to protect and revitalise a 310,000 hectare mainland island in the Upper Mackenzie Basin and Aoraki Mount Cook National Park so that native animals and plants can thrive. The area is home to some of New Zealand’s most threatened plants and animals.

Southern Lakes Sanctuary field rangers install a line of stoat traps in the Kea Basin in the Rees Valley in New Zealand’s South Island. Stoats are a particular threat to indigenous alpine species including Kea, Rock Wren as well as the endangered flightless Takahe which also spend time in alpine areas.

Steven Cox, 27, is a Biodiversity Ranger for New Zealand’s Department of Conservation in the Tongariro District in the central north island. Cox's role is protecting the whio, a threatened indigenous duck, and the North Island borwn kiwi. He's able to monitor their status with radio tracking equipment. "With the loss of each species, we lose part of our national and individual identity," he says.

Paul Ward is the Founder and Project Lead of Capital Kiwi. In 2022, Ward's community group celebrated releasing 11 kiwis on the south coast of Wellington, the nation's capital, where the birds had not roamed for 150 years. It was the culmination of an enormous eradication effort. The group set 4.600 traps over 59,000 acrs to subdue stoatys to a safe level. "The hills are more alive with the call of the kiwi ringing from them," Ward says.

Chelsea Price, 30, is a Rat Dog Handler and Field Ranger at Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) Predator Free South Westland. She feels priviledged to have visited New Zealand's predator-free islands which inspired her eradication work on the mainland. For her part, she "plays detective" with her dog, Baxter, sniffing out rodents. "If we don't do anything," she says, "we're not going to be able to experience the joy of birdsong."

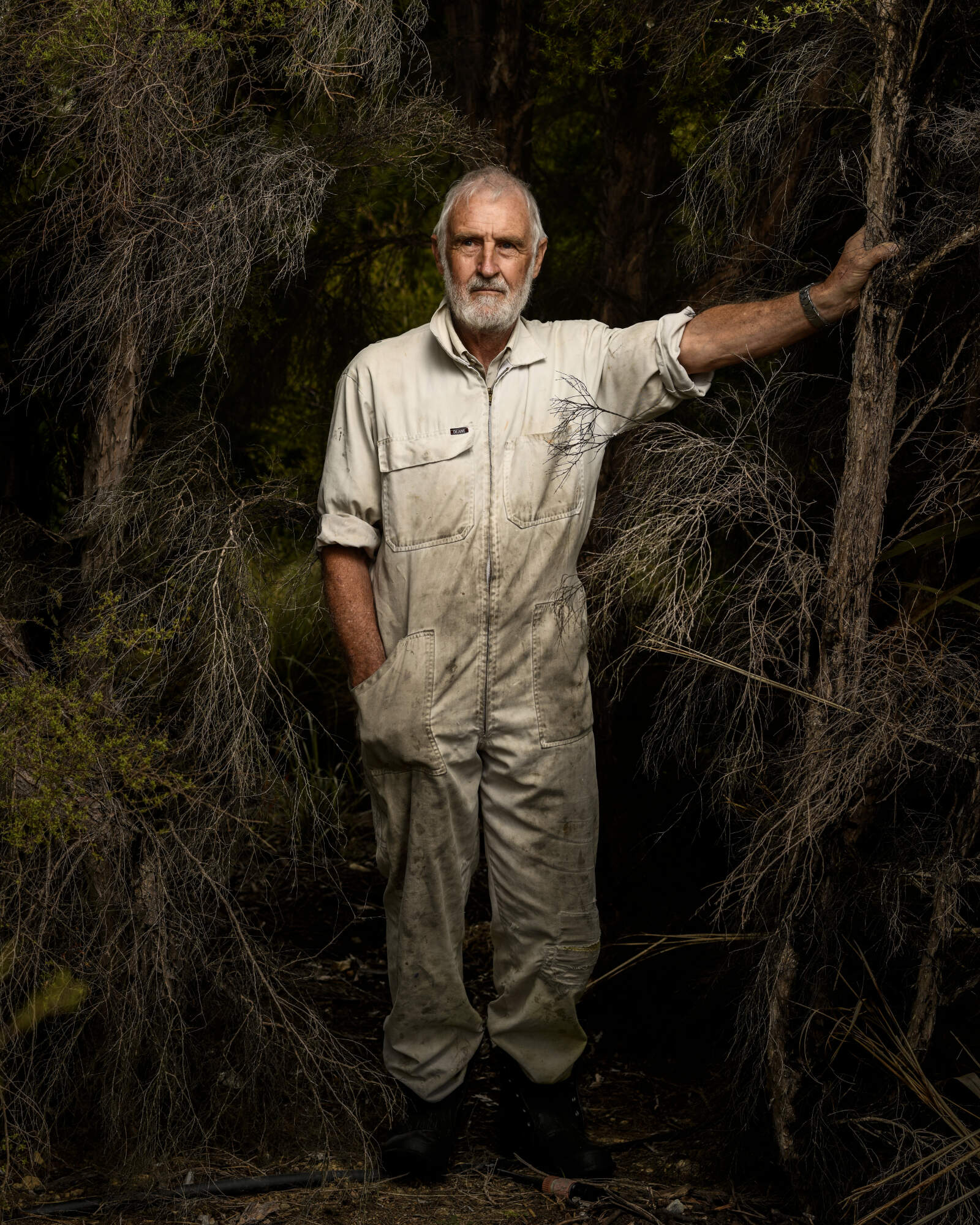

Ian (Mo) Turnbull, 73, is a Southern Lakes Sanctuary Trustee and a Royal Forest Bird Society of New Zealand member and trapper. Eradication workers are motivated by the environmental change they've sitnessed in their lifetimes. When Turnbull was a child, he vacationed in Makarora. in a mountainous area of the South Island, and he remembers the call fo the brightly coloured kea parrot. "Now they've almost all gone," he says."I want to get the wildlife back in Makarora - so I kill rats."

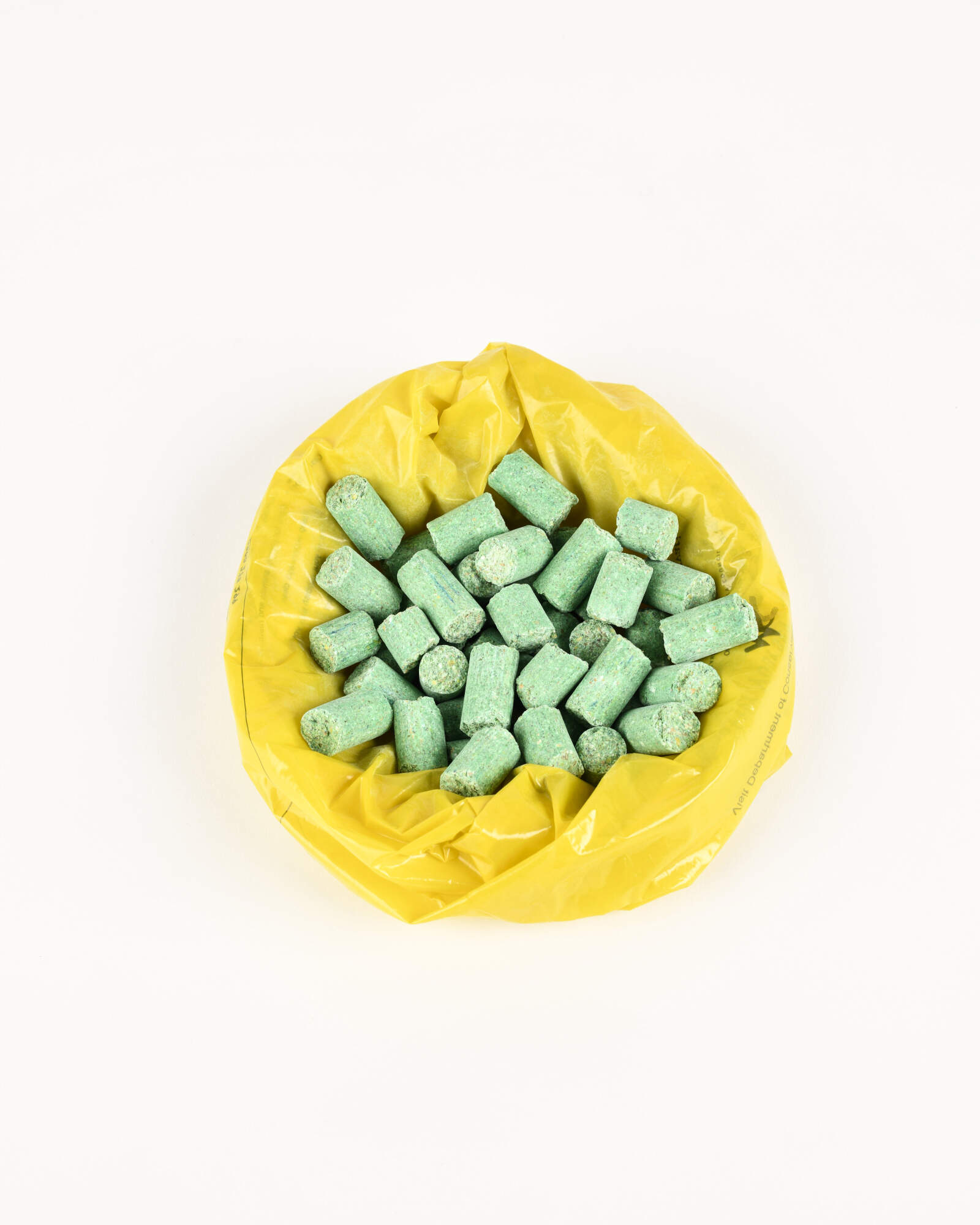

Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) conducts an aerial predator elimination operation which involves the distribution of cereal pallets that contain sodium fluoroacetate, better known as 1080. The toxins target rats and possums, and stoats through secondary poisoning (from eating the carcasses of rats that have ingested 1080).

Jay Manning, a field supervisor from Predator Free Wellington, loads trap boxes made by volunteers for the city's eradication programme.

Joel McGimpsey, from Wellington, New Zealand, is eight years old. He helps his brother and father trap possums and stoats. “We catch possums with a trap that catches them by the leg,” he says. “Me and my brother will come and get them – we’ll whack them with a wooden bat and then pluck them for fur and sell the fur. Someone will weigh it and we’ll get money.”

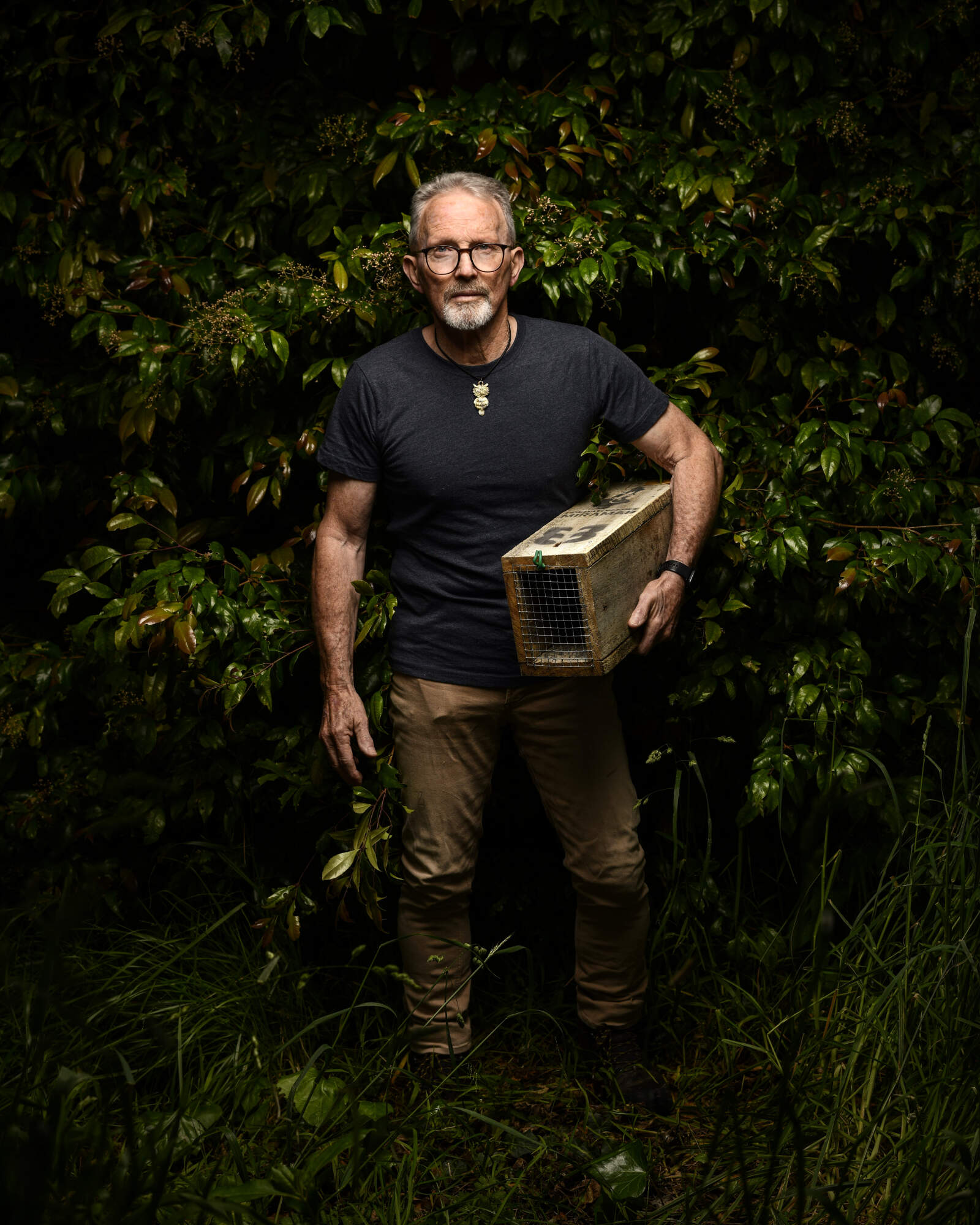

Evan Hamon, 53, is a trapper, the Operational Manager for Te Ranga Wairua, and a member of the Ngati Paorou ki Hauraki tribe. He works with the Maori led organisation to create a trap-based "virtual barrier" to prevent predators from crossing New Zealand's Coromandel Peninsula. His mission is "to save our forest," he says. "The animals keep the forest alive."

Vinuta Koraddi, 25, is a Field Operator for Predator Free Wellington. Vinuta describes her role as follows: “We are the eyes of the team in the field. We are in the bush refreshing bait in our current network of bait stations and traps. In case we find rat activity, we respond to that by identifying potential rat habitats and installing more devices and monitoring devices to catch the rats we might be missing.”

Ross Findlay, 69, is a retired school teacher. He lives in the southern end of Miramar Peninsula and is a volunteer trapper for Predator Free Miramar. “I heard about Predator Free Miramar on facebook and went to a meeting,” says Ross. “From there I became a backyard trapper. I pulled out 50 or 60 rats. I thought I needed to do more, and I was retired so I had the time.” He says that “Every rat I pulled out of the trap I felt a positive impact on the natural wildlife, a benefit to the bush.”

Jay Manning, a Field Supervisor for Predator Free Wellington checks and rebates traps on Miramar Peninsula, the current focus of the charity’s Phase One predator eradication program.

A leghold trap combines a foot plate and two curved bars with a spring-powered action that closes to hold an animal's foot.

The AT220 is a fully automatic self-resetting and self-rebaiting predator trap targeting multi species - predominantly possums and rats.

The Steve Allan SA3 trap targets feral cats, rats, and possums. It is designed to be screwed to a tree or post.

1080 is a an aerially dispersed poison and is currently considered by many to be the most effective pest elimination or suppressant tool in New Zealand. It is used most regularly in areas away from people and livestock.

Department of Conservation staff perform a final health check and attach transmitters on to the backs of takahē before releasing them into the wild. These 10 birds, who have been bred at The Burwood Takahē Breeding Centre, or come from sanctuaries, will be joining a resident population of 220-240 birds in the Murchison Mountains in Fiordland National Park in the South Island of New Zealand. Until 1948 takahē were thought to be extinct. When they were rediscovered in the Murchison Mountains, it is estimated that there were less than 200 birds left. The

Department of Conservation staff and local Iwi elders representing Ngai Tahu Whanau Whanui Ki Murihiku release 10 takahē birds, who have been bred at The Burwood Takahē Breeding Centre, or come from sanctuaries, into Top McKenzie, Murchison Mountains, Fiordland. They join a resident population of 220-240 birds in the Murchison Mountains. Until 1948 takahē were thought to be extinct. When they were rediscovered in the Murchison Mountains, it is estimated that there were less than 200 birds left.

Kiwi tracks in Tongariro Forrest Kiwi Sanctuary, central North Island.

Banks Peninsula, New Zealand.