1. Stopping Fall Armyworm

For Bello Abu Bakkar and his community in southern Nigeria, the appearance of a very small creature was the beginning of a very big problem. The maize farmer and president of Nigeria’s Maize Association knew that something had to be done.

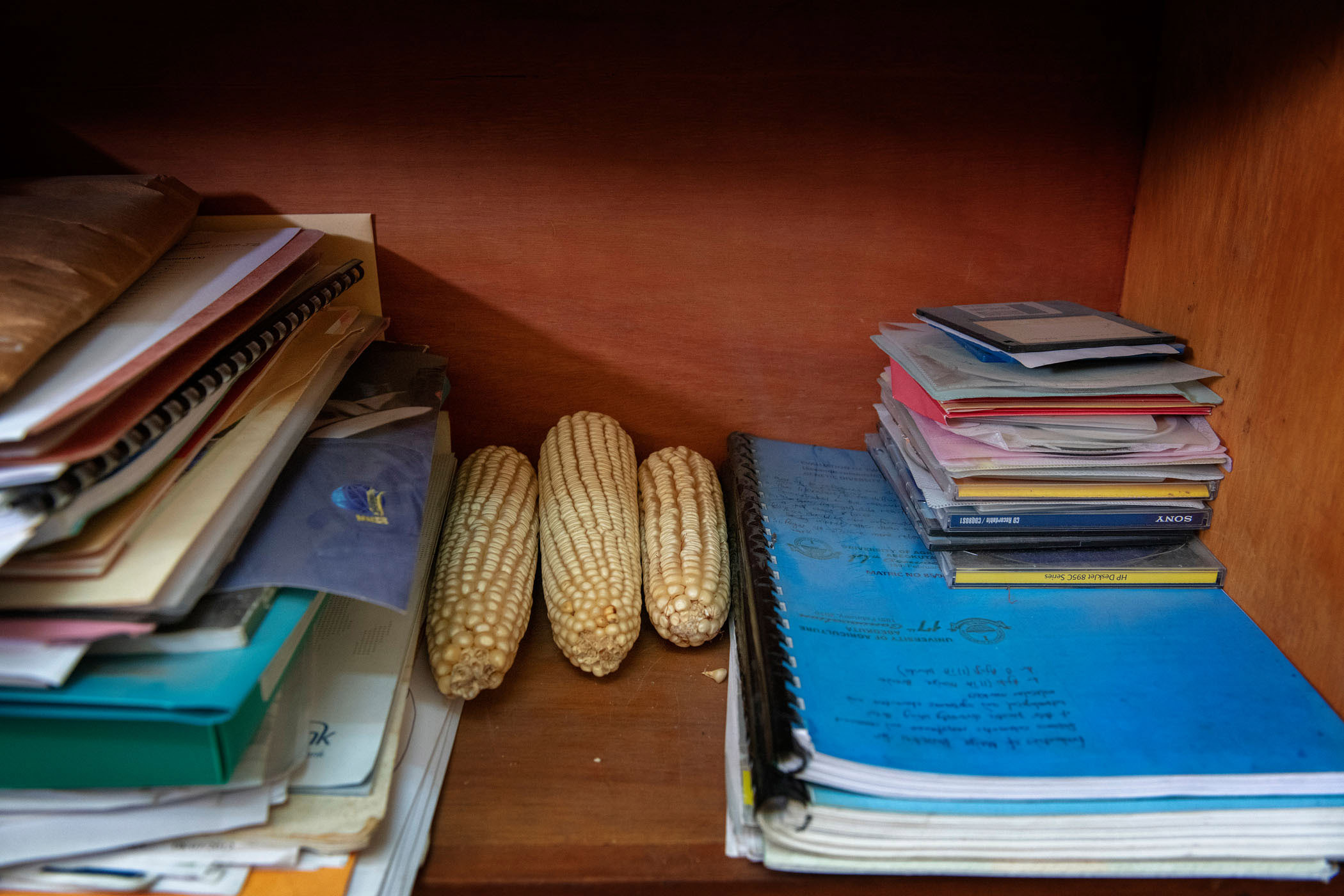

In its larval stage, the fall armyworm – Spodoptera frugiperda, of the order Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, which grows to become a moth later in its life cycle – poses a huge threat to farmers.

Migrating up to 500 kilometers per generation, the fast-spreading pest feeds on more than 80 crop species, including maize. Due to its rapid reproduction rate and destructive capacity of plants at different growth stages, it can destroy entire crops almost overnight.

The name “armyworm” refers to the species’ invasive behavior. Reports of the fall armyworm’s appearance in Nigeria started in January 2016 in the southern state of Oyo. By June the following year, the pest had spread to 22 of the country’s 36 states. The year after that, it was present in all states and the Federal Capital Territory.

As maize growers, Bello and his community were concerned for their livelihoods. The fall armyworm invasion was estimated to pose threats of $3-6 billion in annual damage to maize and other crops on the African continent.

With maize as an everyday staple, the community was not only worried about their income, but their food security as well.

But on closer inspection, it seemed that the invasive pest preferred some maize varieties over others.

Dr Abebe Menkir and other scientists and breeders from the CGIAR Research Program on Maize (MAIZE) took advantage of the high level of infestation of the pest as an opportunity to identify which maize varieties and lines showed greater tolerance.

The more tolerant maize inbred lines were selected for use to develop synthetic and hybrid varieties, which are now being tested under both artificial and natural infestation.

Artificial infestation with fall armyworm larvae is being used to further screen adapted maize inbred lines for tolerance to the pest. The most tolerant lines will be used to develop varieties and hybrids intended for further testing and use by farmers like Bello.

Scientists are also screening inbred lines introduced to Nigeria by the Agricultural Research Service at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-ARS). The lines, which have shown resistance to the pest in the US, are being screened under artificial infestation with the type of fall armyworm now found across Nigeria.

In eastern and southern Africa, the maize team working under MAIZE are also making intensive efforts to identify and develop improved maize hybrids with genetic resistance to fall armyworm.

The pest-resistant maize varieties are expected to become a complementary component of a management strategy that includes biological control agents, pesticides and other options for controlling damage to local food crops.

2. Maximising groundnut production

Five years ago, Talatu Idrissa and her neighbors each received a small, five-kilogram pack of groundnut seeds. Together, they are now producing up to 3.5 tons of groundnuts a year, and are using the interest from their savings to support their community.

Talatu leads a group of 25 women who are making the most of a new high-yielding variety of groundnut in the village of Bunkure in Kano, Nigeria.

The women keep most of the groundnuts to feed their families, but there is now enough to process into products like oil and cakes to sell at the market. Their earnings are gathered in a communal savings box and deposited in the bank, where they can earn interest.

With the interest from the money saved, the women have been able to support one another through childbirth, send their children to school or even university, and restore the local health center and elementary school – earning them recognition from the Kano state governor in 2015 for their contributions to the community.

We process the farm produce together and we share the profits.

Talatu Idrissa - group leader

“When we make groundnut cake [or oil], one or more of us will take it to the market and sell it,” Talatu says.

“We use the profit to lease a plot of land. We process the farm produce together and we share the profits.”

In a country where women struggle to gain access to land, Talatu and the women in her group have found that they are stronger together, using their collective resources to access land and bulls for farming.

They haven’t kept all the benefits to themselves. The group have used their resources to repair the doors and windows of the local school building, and to fix beds and provide supplies for the health center.

This has resulted in better services for the whole community.

“Earlier, people avoided visiting the hospital when they were sick, because the hospital was in such bad condition. Nurses refused to stay overnight,” Talatu says.

“Now that we have cleaned up the premises, they are no longer afraid to stay long hours in the hospital. In fact, the health center now offers 24-hour service and nurses are ready to attend to patients at any time of the day or night.”

The improved groundnut variety seed they use is known as SAMNUT 24, which contains more oil and provides higher pod and fodder yields compared to local varieties.

The original improved variety seeds were distributed through the CGIAR Research Program on Grain Legumes and Dryland Cereals (GLDC).

Talatu’s group says that they now produce 25 bags of groundnuts on one hectare of farmland, which is nearly double of the 13 bags they got on the same farmland. They also make extra income from the haulms, or stalks, sold as animal feed. Profits from haulm sales were used to start dry season groundnut production in 2018.

Dr Hakeem Ajeigbe, GLDC Country Representative in Nigeria, says it is important to keep innovating, not only with seeds but with farming practices as well.

“We need to keep innovating because, for example, the rainy season – or rather, the planting season – is becoming shorter, but the rain sometimes gets even higher, so we have to adapt varieties that will be tolerant,” he says. “We get the new, improved varieties, but at the same time we need improved agronomic practices to eliminate [the] challenges.”

Talatu and her group are ready to keep learning new skills to adapt their practices to a changing climate.

As with their crops, their community is bound to reap more than they sow.