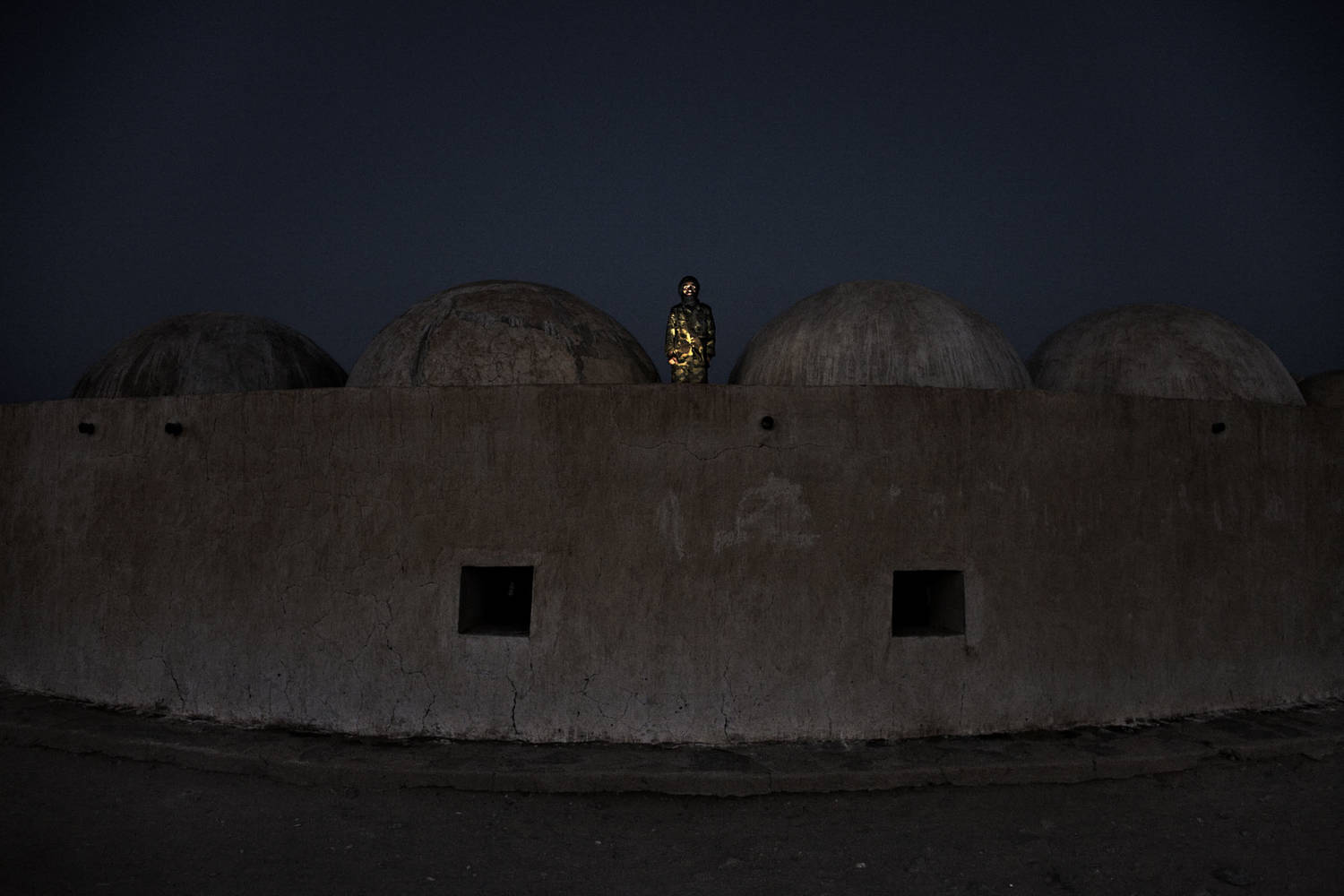

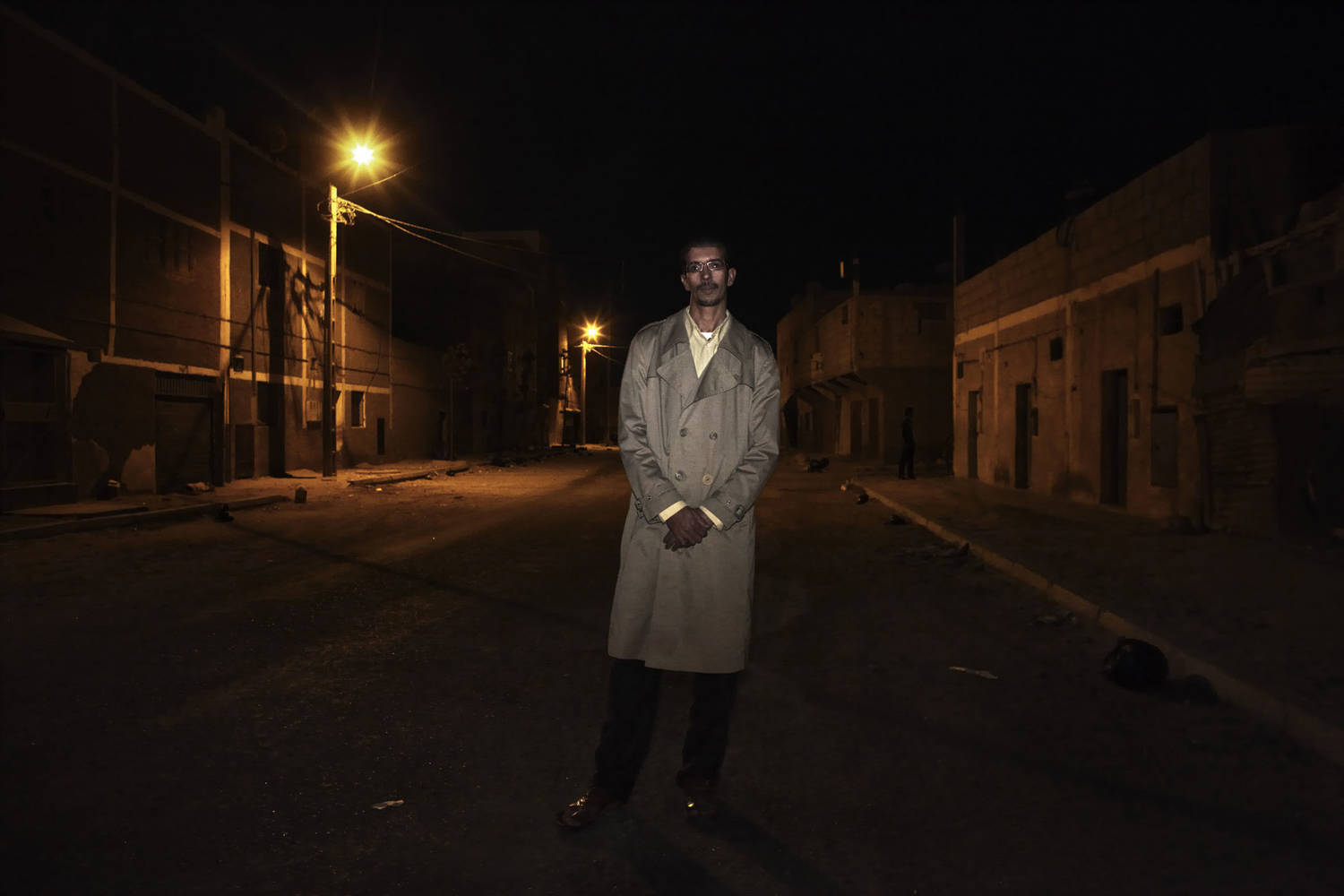

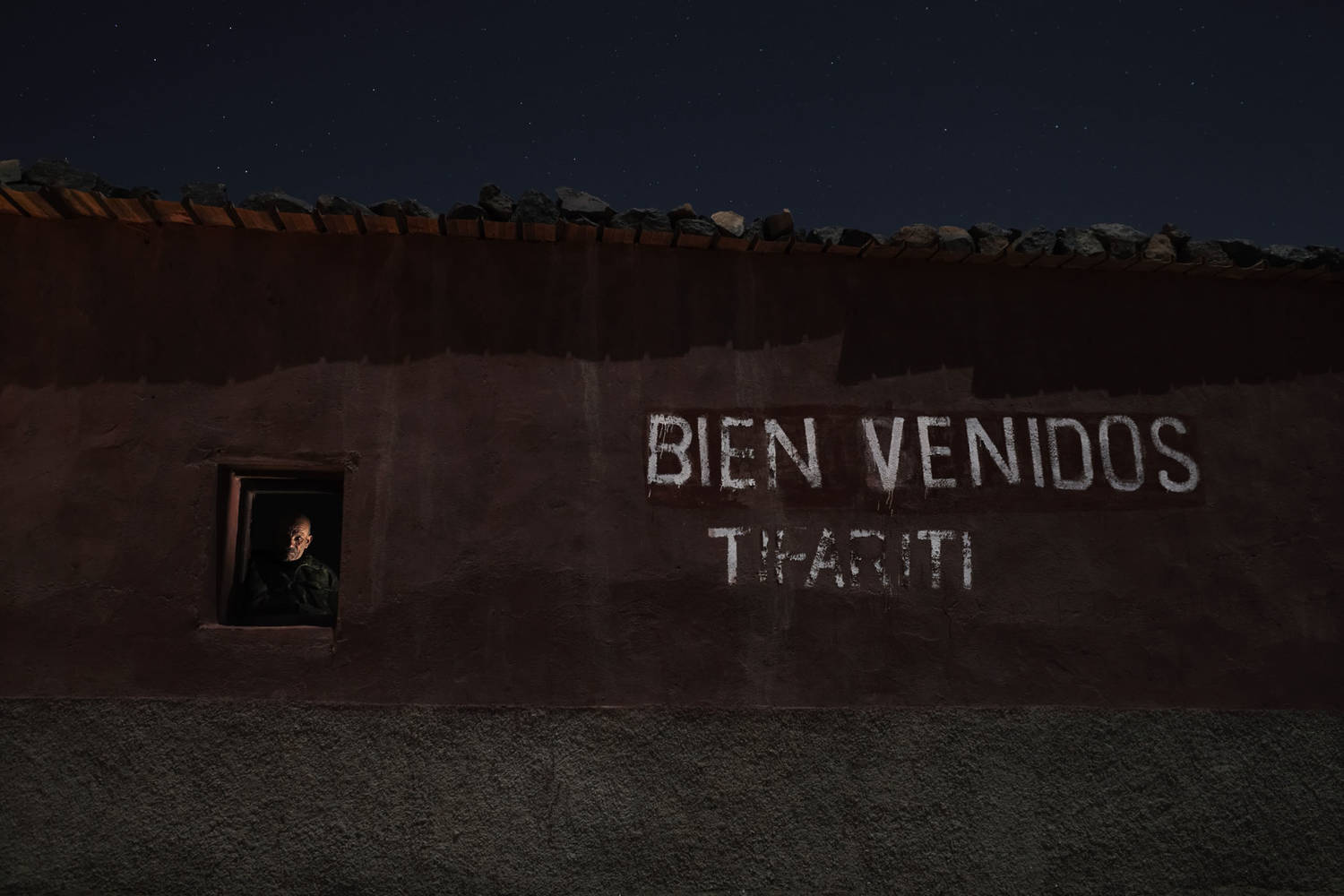

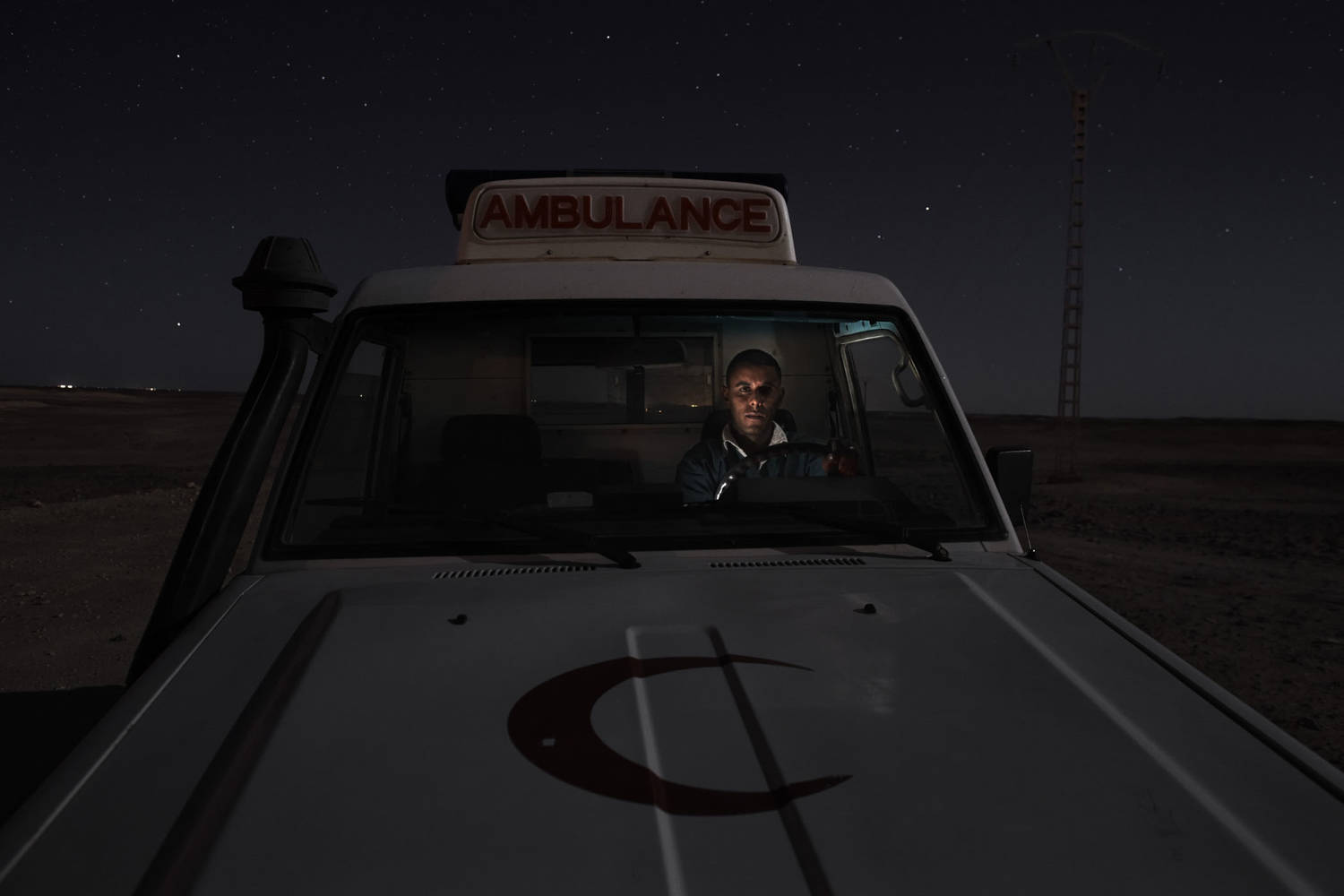

For over 40 years Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony in northwestern Africa, and its people, the Sahrawis, have been living in geopolitical limbo, invisible to the world and largely forgotten. They live in perpetual darkness.

Western Sahara is Africa’s last open file at the United Nations Decolonisation Committee. Occupied by Spain from the end of the 19th century until 1975, the territory was left to joint Moroccan and Mauritanian administration as Franco’s rule drew to a close and Spain relinquished its African colonies.

A UN mission in the same year found that neither country had an overriding claim to Western Sahara and that the people of the territory had to be consulted about their future. Yet as war broke out between Morocco and Mauritania over the resource-rich region, military force replaced diplomacy with the Polisario Front, a Sahrawi nationalist militia, joining the fray and fighting both countries.

After declaring the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in January 1976, Polisario launched an insurgency against the two neighbouring countries which became a drawn-out 16 year armed struggle against Morocco once Mauritania withdrew its claim in 1979, allowing Morocco to assume full military control.

While making some early gains with heavy backing from Algeria, another protagonist in the multi-sided dispute, Polisario’s efforts were increasingly hampered from the mid-1980s onward by the construction of a heavily mined 1,600 kilometre sand wall which divided the territory in two, leaving Morocco in control of the coastal strip and confining the Polisario to the inland desert and the areas around the refugee camps that sprung up in Algeria’s Tindouf province across the border.

The population of Sahrawi refugees in Algerian refugee camps has grown to some 170,000 over the years with another 30,000 living in Mauritania and a few thousand in Spain. The remainder of the Sahrawi population has been significantly diluted by an influx of Moroccans, encouraged by their government to move south to consolidate Morocco’s hold over the territory.

By the early 1990s, fighting had largely decreased to the occasional skirmish and in 1991 a UN-sponsored ceasefire was agreed between Polisario and the Moroccan government with a referendum planned for 1992. Yet preparations for the referendum quickly stalled, mainly over the contentious point of who would be eligible to vote.

Polisario wanted to base the referendum on the 1974 Spanish census, while Morocco claimed that the census was flawed and wanted Sahrawis living in Morocco proper to be included. For the past 25 years the two sides have continued to wrangl over the terms of the referendum, leaving the Sahrawi people to languish in limbo with yet another generation growing up in refugee camps, uncertain of the future.