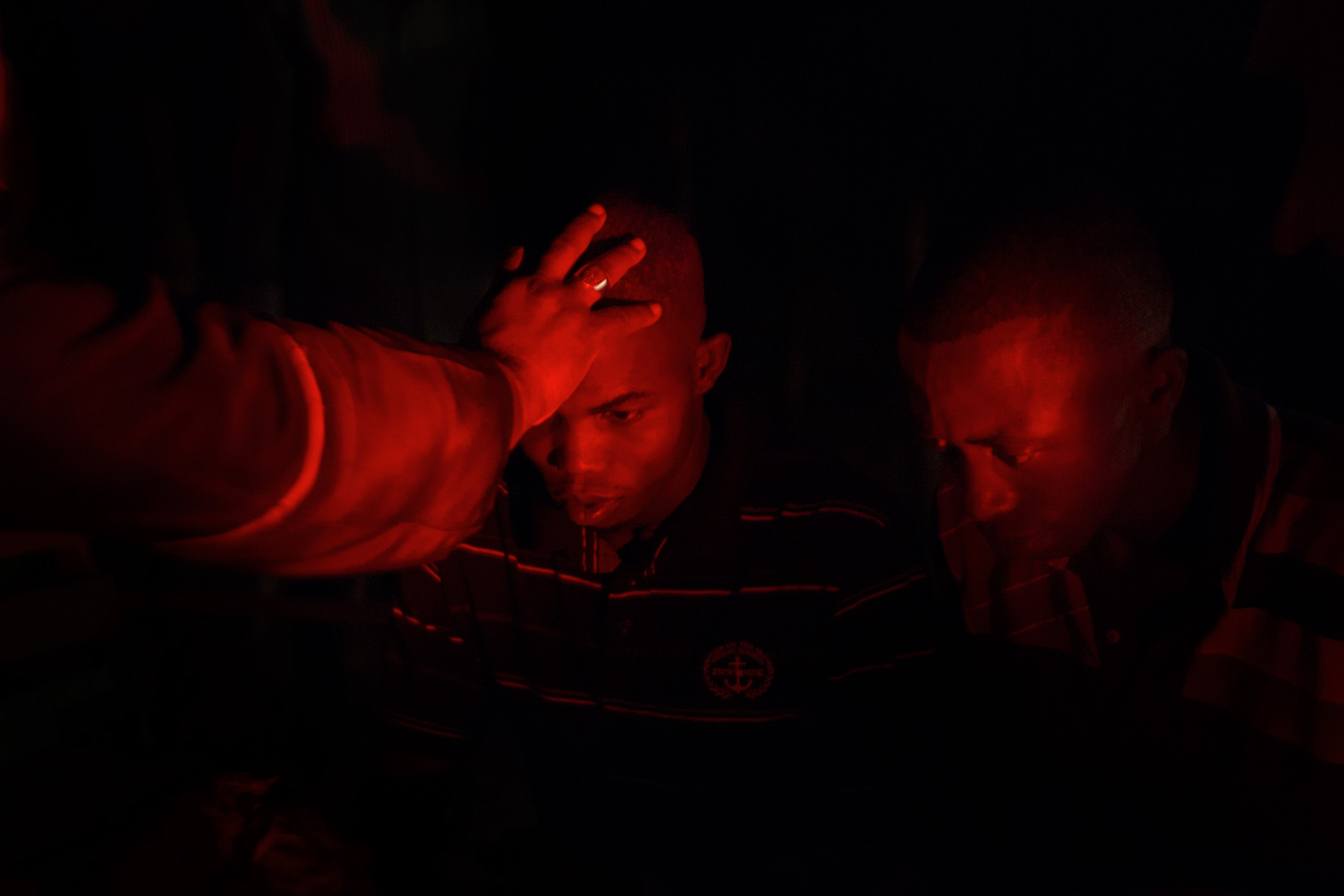

Here, hand grenades which cost the same as small candies have flooded the market and the lack of future prospects makes it easy for militias to attract young men.

The Central African Republic (CAR) has seen more than its fair share of coups and unrest over the five and a half decades. In December 2012, a rebel coalition calling itself ‘Seleka’, meaning ‘Union’ in the local Sango language, toppled the government of President Francois Bozize, accusing him of not abiding by the terms of earlier peace agreements signed in 2007 and 2011 which ended earlier conflicts. Rebel leader Michel Djotodia declared himself president and was recognised as a transitional head of state at a regional meeting in April 2013.

Though Djotodia soon declared Seleka disbanded, renegade rebels continued to loot, rape and pillage and the conflict began to develop along sectarian lines with the mainly Muslim Seleka fighting Christian vigilantes calling themselves Anti-Balaka (or Anti-Machete).

William Daniels has been to Central African Republic on a number of occasions since the outbreak of the violence to report on the disintegration of an African nation. His last trip was in March 2016.

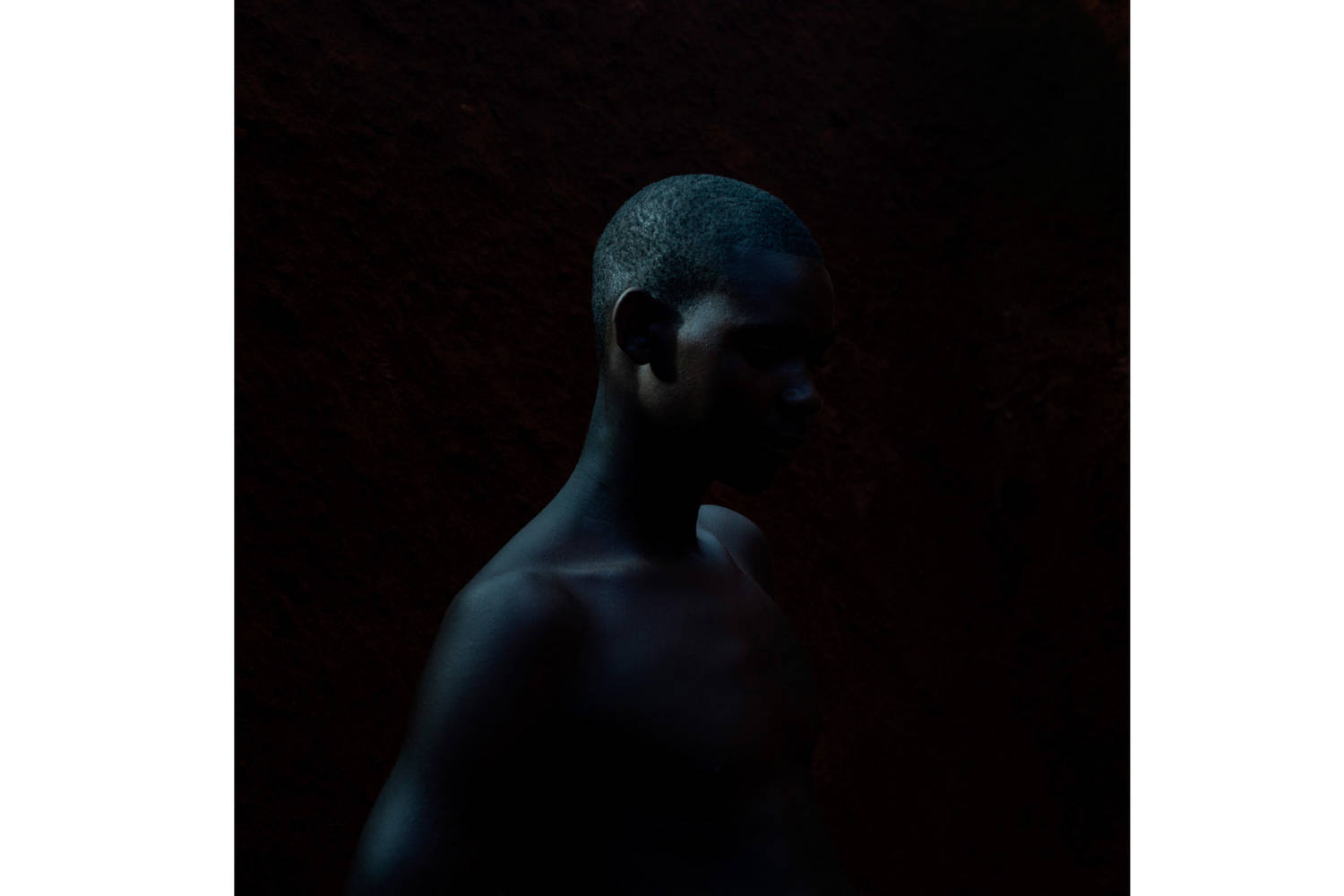

“When I first visited CAR, the country had just descended into the most serious crisis of its short history. In 2013, rebels from the Seleka alliance, a predominantly Muslim militia, overthrew the government, unleashing nine months of anarchy in the sparsely populated country of five million. In response, Christian and animist militias, calling themselves ‘anti-Balaka’ rose up against the rebel government, launching attacks on their opponents and on Muslim civilians suspected of being Seleka supporters.

At first I covered this conflict mostly for news media outlets such as TIME Magazine which had committed to covering one of the world’s most neglected crises. But soon I felt that this was only one part of the story. After making several trips to CAR I emerged with an acute curiosity about the roots and context of this tragedy. I had a burning desire to show the unseen side of this war. I had many questions in mind.”

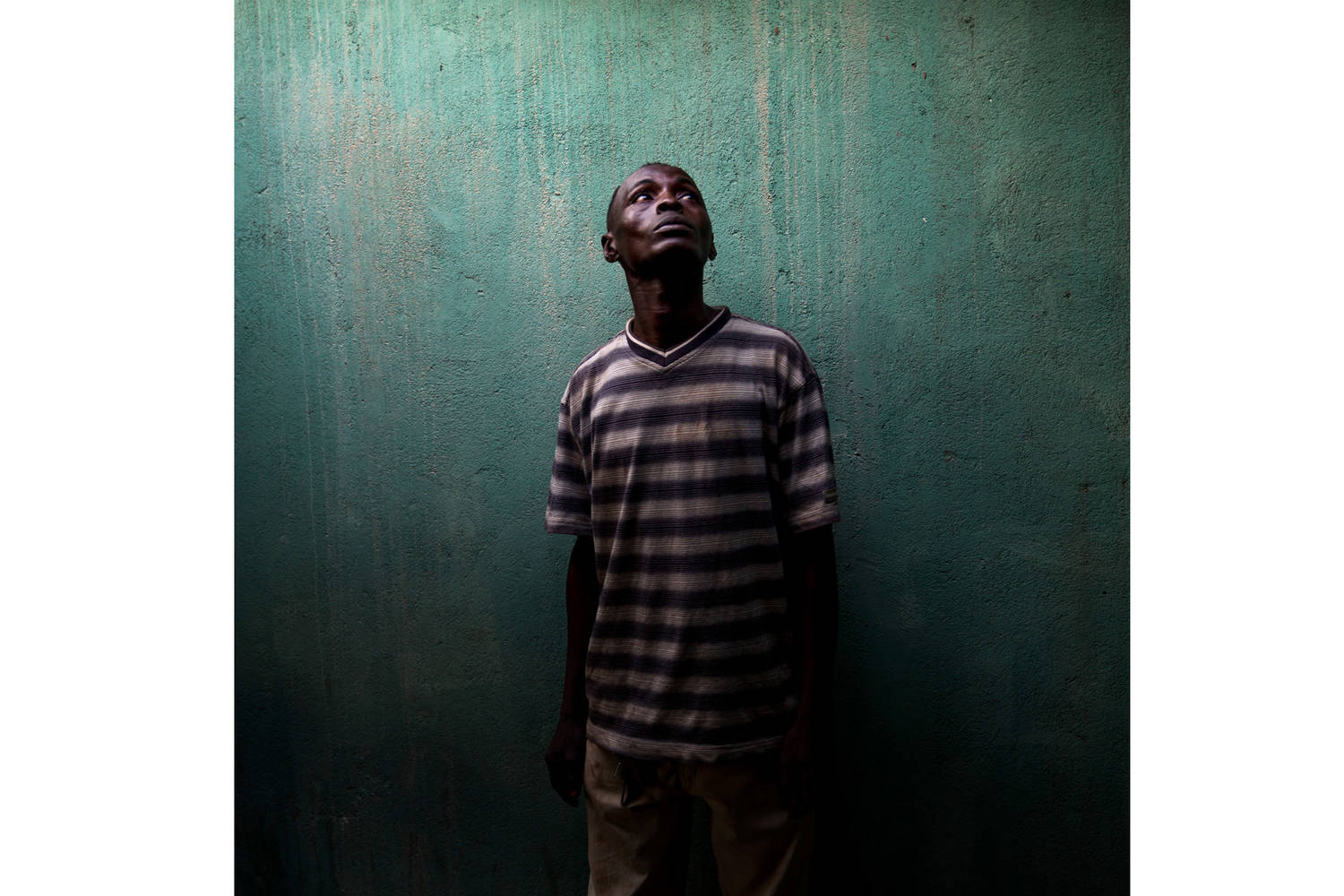

How can this young country shift so suddenly to such violence? How can a country whose soil is often described as so rich be so poor? How can a state be so fragile – and so easily overthrown?

My goal was to document CAR behind the headlines.

“Central African Republic has been vulnerable ever since gaining independence from France in 1960. Systemic corruption and meddling by external players have resulted in multiple coups d’etats.

Widespread misappropriation of the country’s vast natural resources has deprived the general population of their economic benefits and caused the state to need constant propping up by foreign donors.

The judiciary is dysfunctional, leading to complete impunity, while the national army was no match for Seleka rebels who took over in 2013.

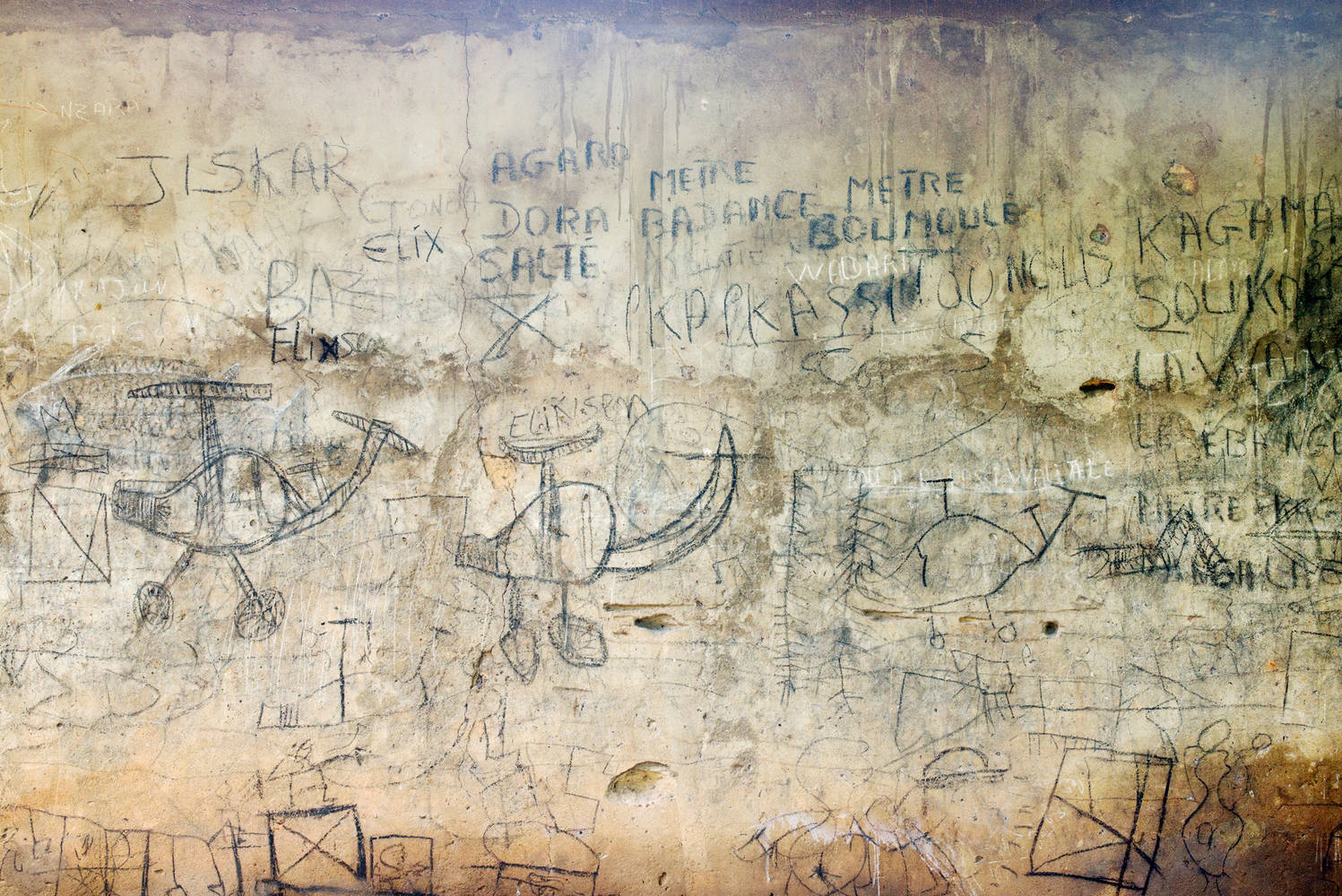

CAR remains one of the worst places on earth to gain access to health services and malaria and chronic malnutrition continue to stalk the country leading to untold numbers of unnecessary deaths. In 2014, the UN Development Program rated CAR as the second least developed country in the world, ahead only of Niger but with a much lower life expectancy and a much lower Gross National Income (GNI). To this add close to a million displaced people – a fifth of the country’s population – many of whom have taken refuge in neighbouring Cameroon and Chad. More than a third of CAR’s children have never set foot in a school.”

“Thanks to the Getty grant and the Tim Hetherington grant I travelled to CAR on 6 occasions between September 2014 and March 2016. I worked in regions that have been abandoned by the state for decades. I shot in diamond and gold mines controlled by armed groups.

I documented the country’s faltering health system which is almost entirely dependent on NGOs such as Medecins sans Frontieres, an organisation that is currently the third biggest employer in the country.

As CAR has completely disappeared off the news agenda, and while violence has subsided slightly over the past months, the country remains on the edge, facing a very uncertain future.”

William Daniels