Kenya

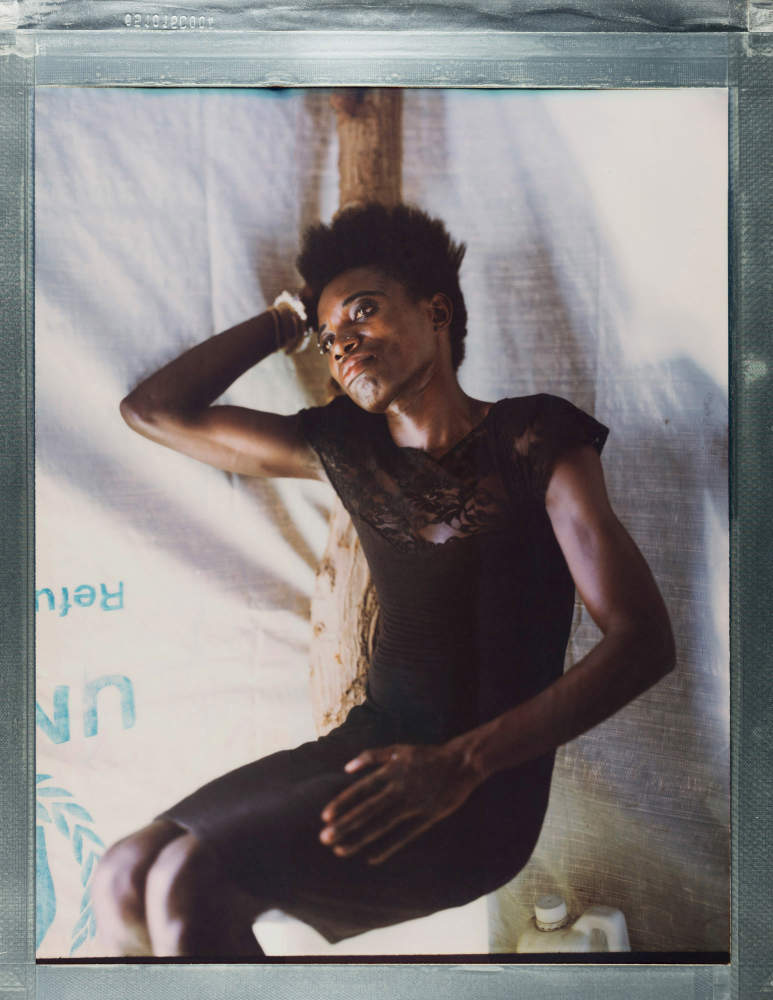

Beyonce

Beyonce is a Ugandan refugee living in Nairobi where she is supported by Nature Network. Beyonce left Uganda after her family discovered that she is transgender.

“I’m from Uganda. I’m a proud transgender, but I’m in Nairobi as a refugee. I ran away from Uganda because my family and the community found out that I’m gay. I was beaten to death, but I survived. But my family continued to look for me. They also went to the radio station. They say that whoever sees me they should contact them or to kill me. That’s when I ran to Nairobi in 2015.”

Beyonce came to Nairobi hoping to find a safer life than in Uganda, however she often still finds intense discrimination towards LGBTQI+ people.

“In Nairobi it’s very difficult as transgender women or transgender. We found life very difficult. Also in Nairobi people are homophobic. People try to threaten you. People try to attack you, because they can’t allow gay people in their country. It’s very difficult and I myself I can’t move around, because a lot of community and people are homophobic, so it’s very difficult here. There’s a high risk for LGBT to get HIV, because their clients may say that ‘I’m paying you $20, but I don’t want us to use condom. This person, the LGBT refugee he may, because he needs the money, so he will risk his life then he sleep with the guy. There is a high risk for that. I hope my future it will be like … to have a freedom, to be who I am and to do something that I can do when someone can’t stop me. When someone also can love me, where I can be loved.”

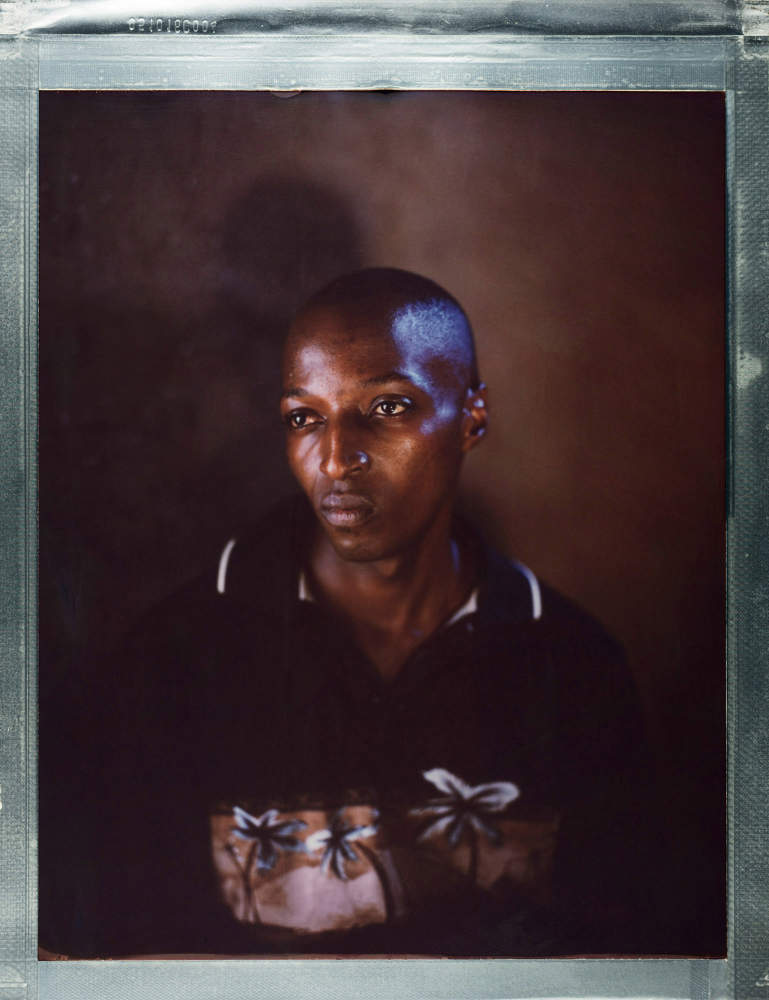

Moses

Moses (25) is a refugee from Uganda who has resided in Kakuma Refugee Camp in north western Kenya since September 2017. In 2015 and 2016 Moses was arrested by the police while attending LGBTQI+ events in Kampala. On both occasions his image was released to the media who used photos of him and other community members in homophobic articles. This led to him being thrown out by his landlord.

After moving from place to place he was given some money by a friend in the US to leave the country and seek refugee status in Nairobi. After registering as a refugee he was transferred to Kakuma Refugee Camp in the arid north western quarter of Kenya. Rather than sanctuary, he encountered further homophobia and substandard living conditions.

“Reaching here, I found that place was so terrible and the situation will remain that same situation, that same previous I was facing in Uganda, and the same problem I found myself facing in here.”

Ronnie

Ronnie, a Ugandan refugee and LGBTQI+ activist with Nature Network. Ronnie’s mother supported him in Uganda, knowing he was gay, but after her death he decided to leave the country.

“My mom had already discovered my sexuality without even telling her anything. She advised me to keep a low profile and have one person because there are a lot of diseases in gay community. She also told me to go slow as the community and culture do not accept homosexuality, and if they knew, I would be killed, disowned, imprisoned, abandoned and cursed. The community came to hear rumours of me being gay and they looked at as a taboo, but my mom never stopped accepting and defending me. Unfortunately, after a few years she died an abrupt death and that was all of my life because she was the only person I had. She was the only person I had, someone who supported and defended me.”

Ronnie met a Kenyan man through Facebook who encouraged him to come to Nairobi. After arriving in Nairobi, the man refused, encouraging him to earn money through sex work. Without valid ID or legal status Ronnie engaged in sex work to survive, aware that he was making himself vulnerable to HIV. “I met the guy. We went to his place, but after using me, he started telling me how he can’t stay with someone who doesn’t work as he’s not financially stable. But, he can connect me to some people. I can give sex for money as I earn a living.”

Ronnie now is the leader of the Nature Network which works to provide support to LGBTQI+ refugees. As many refugees turn to sex work to survive, much of Nature Network’s work revolves around HIV/AIDS prevention and awareness. “Many of us have acquired HIV from rape because some people know they are living with HIV and they rape refugees, end up getting HIV. Sex work, a lot of refugees engage in sex work to earn a living. Not that they want, but because of the situation they are living in.”

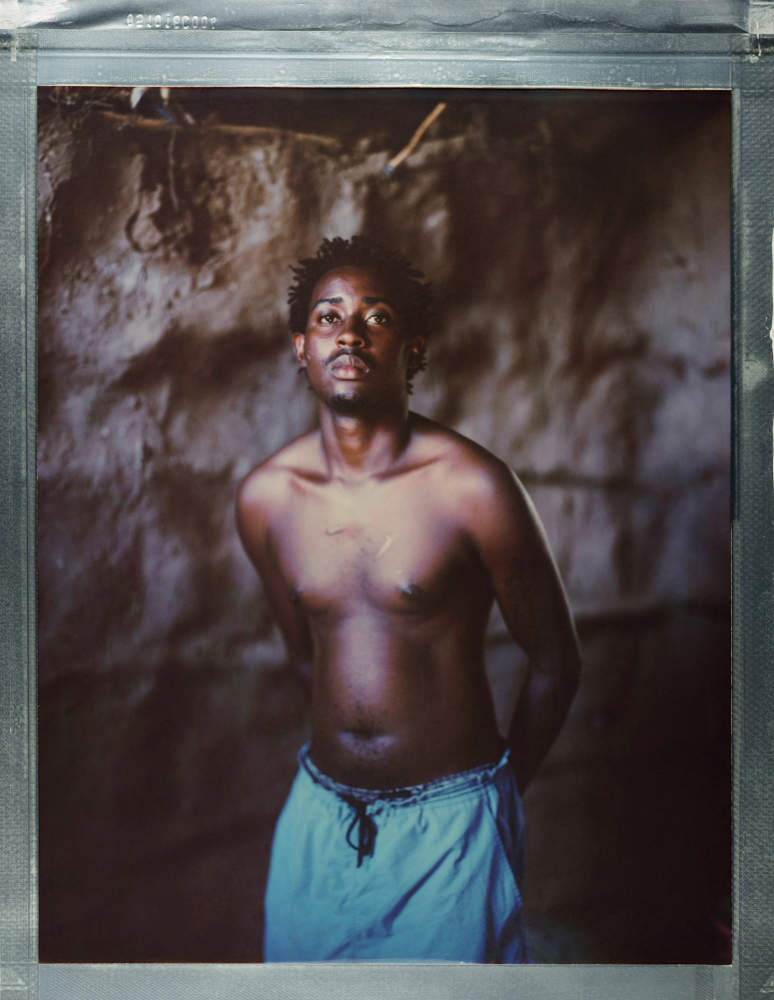

Sudi

Sudi from Rwanda, who was born HIV positive, to a HIV positive mother. He hid being gay for 24 years, but after coming out, was forced to leave home and is now in Kakuma Refugee camp.

“People used to point to me, I cannot fetch water. That why I come to hide here, myself, the best way that isn’t people who doesn’t know me, who doesn’t know my status, who doesn’t know that I’m LGBTI, who doesn’t know that I’m infected by HIV. I live like someone who doesn’t have a home. To be a refugee is something that make me first to be pain. We used to face a lot of issues in camp. Today I breathe, tomorrow I cannot breathe. That is the way we live.”

Sudi is choosing to be open about his HIV status hoping to reduce the stigma others with HIV/AIDS feel. “I told those people who have hormones like me, to be open, who have infected of HIV, to be open. To have HIV doesn’t mean that you can die. I live until now. I go to things, use your medicine, and don’t think a lot.”

Sudi believes that a community should support each other. “This is a message I pass to your friends: if you know your friend have a problem, don’t run from him. You two are like that. Stay with him. Give him hope. All of the world is not in Kakuma only. Every place where there’s LGBTI like us, help them.”

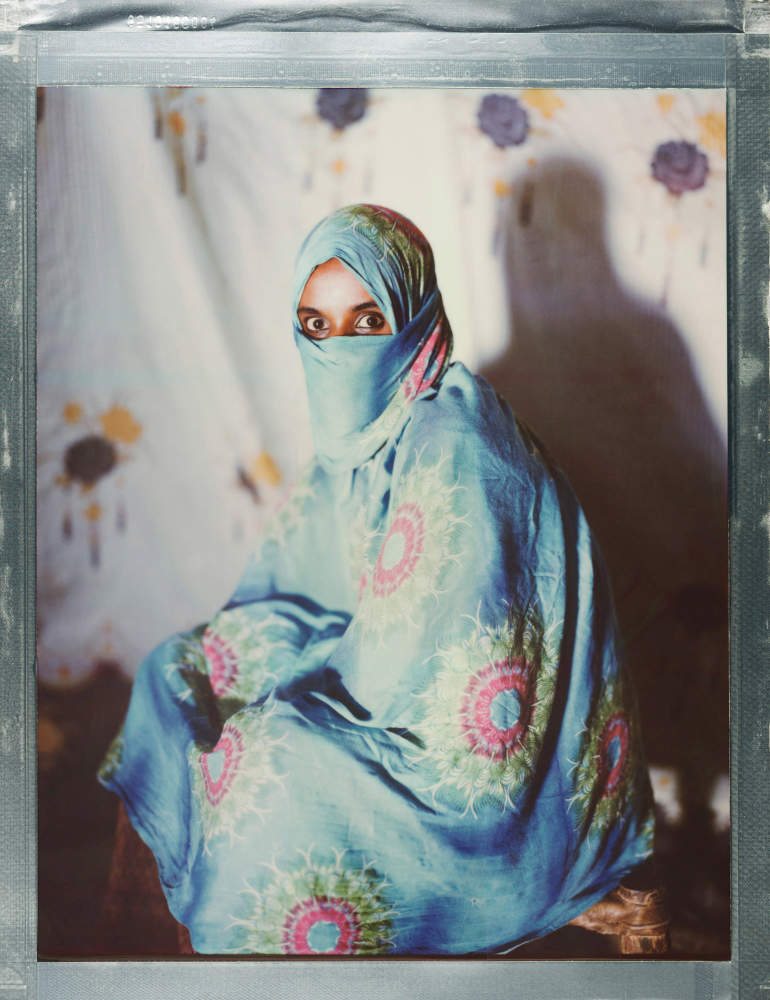

Nakitende Aisha

Nakitende Aisha says she knew she was lesbian when she was 13 years old. She describes her family’s reaction. “My family members want to kill me after they found out that I am a lesbian. Even villagers wanted to kill me. My family told the villagers that in case they saw me, they should kill me. That my family would pay them.”

Her village was not safe, but neither were the streets of Kampala. In 2000 walking back from the country’s only LGBT bar (since closed by the President) she was beaten with a metal pole and gang raped. “I get to realise I was sick in 2014. That is after I started to fall sick frequently which was never the case for me.” Aisha tested positive for HIV. Given that she did not have sex with men, she presumes she contracted the disease when she was raped. Fearing for her life she fled her native Uganda for Kenya.

She describes how life is here in the country where she seeks sanctuary. “Even in Kenya, the neighbours don’t like me. They abuse me saying I am a disgusting lesbian… we are not at peace even here in Kenya.” She has continued to face attacks here in Kenya and after one particularly violent one, lives in fear. “I am always scared, worried that they could come back and kill me because they had machetes and they were 15 in number. So I worry that they could come back and behead me… my heart has never been at peace since then. It is always pumping hard. I am always worried that those men could come back and kill me here in Kenya.”

Aisha, like all LGBTQI+ refugees in Kenya hopes to be resettled to a country that will accept her for who she is. The emotional turmoil of her circumstances, and lack of any hope weighs heavily on her. “For the future, I feel like committing suicide because I am not happy at all here in Kenya… Only God knows. We are just strong hearted but people hate us.”

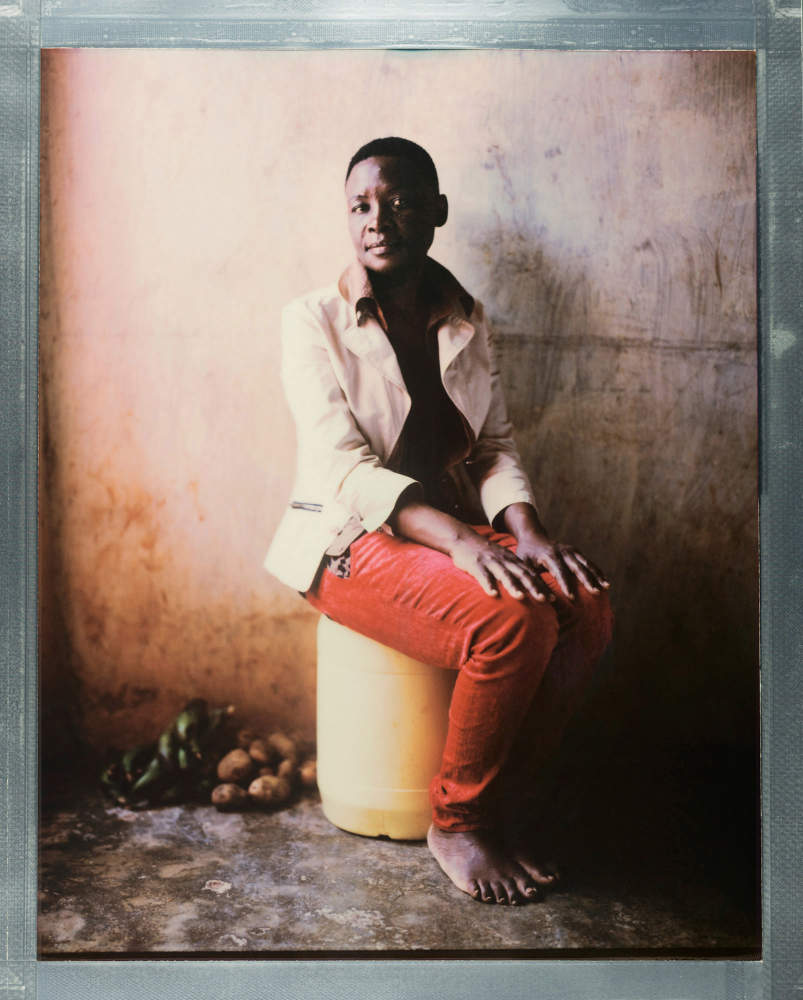

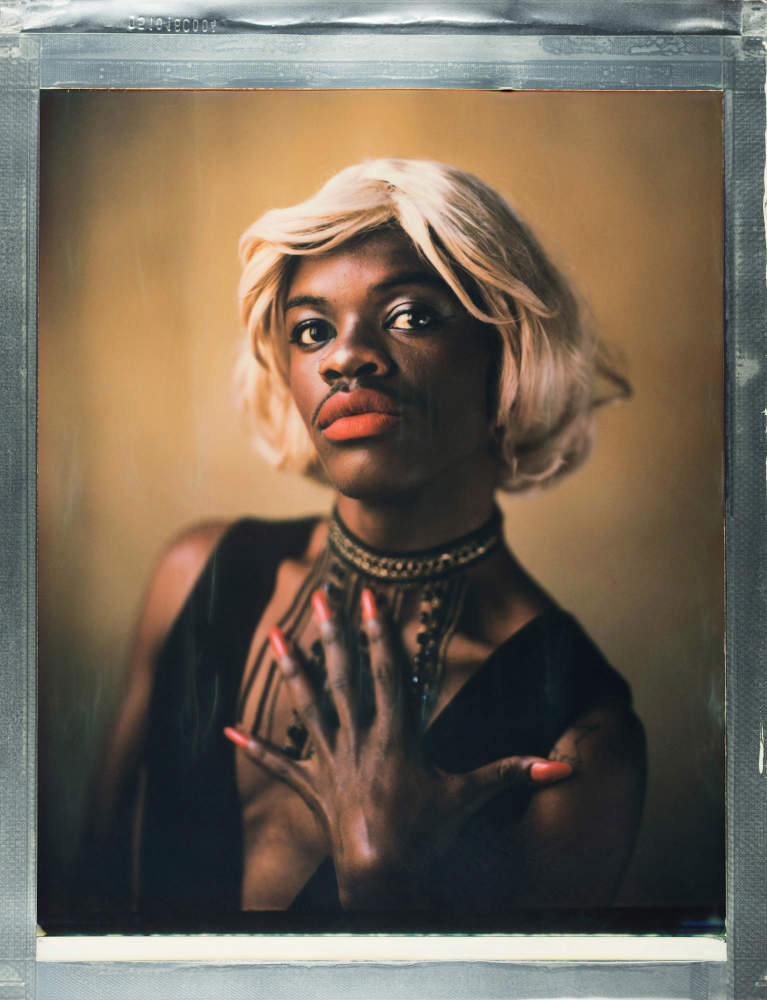

Kuteesa

Kuteesa at Kakuma refugee camp in north western Kenya where she met her partner, a gay man also a refugee from Uganda.

Kuteesa identifies as a transgender woman and fled her home country of Uganda to seek sanctuary in Kenya as a refugee. She has found neither safety, nor hope. Even the refugee camp, run by the UN is not safe. She suffers death threats and discrimination from others in the camp. Moving around is not safe as Kuteesa explains.

“Whenever we try to fetch water, there are so many people outside there who are not gays because we lack piped water in our home, even going out to buy some food, the shops don’t sell to us. They refuse to sell to you because you are gay and that is why we no longer purchase some things.”

Even seeking health care is not safe. Kuteesa says “We are so far from the hospitals and so can’t walk there because if you do, you can be stoned to death. Even if you are sick, you have to just suffer in case you fail to get someone to escort you to the hospitals… Everywhere you go, people ridicule you, and we are so misery now.”

She hopes to be resettled. “I would like for us to have enough freedom to live freely without having to hide our feelings in public just like it is in some foreign countries,” says Kuteesa.

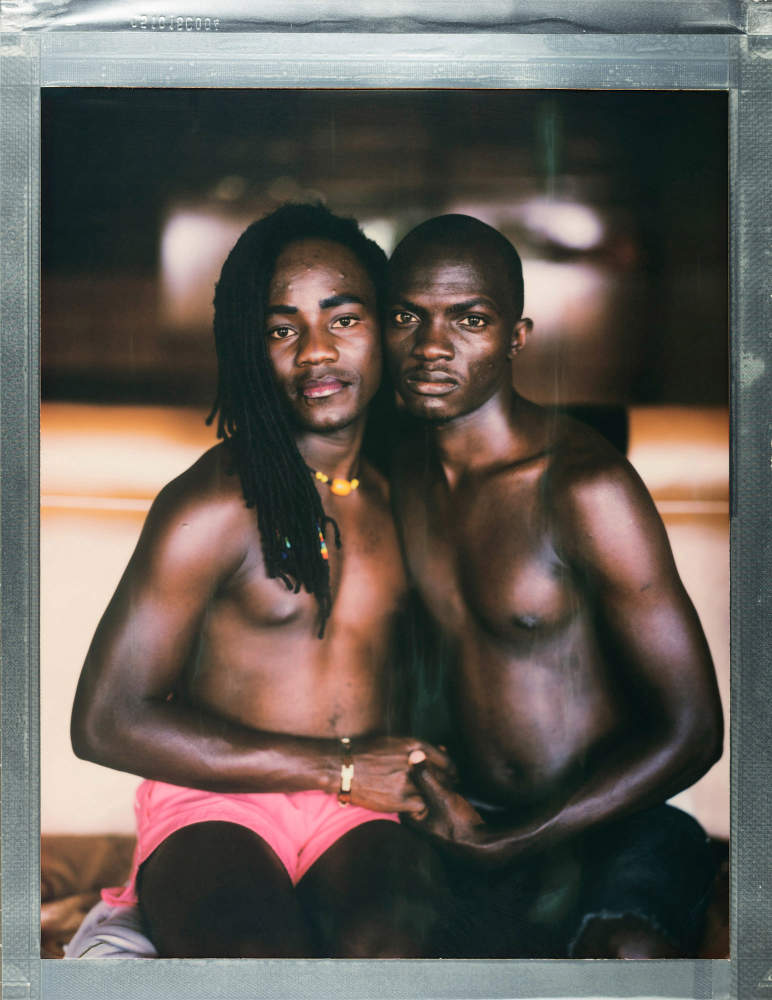

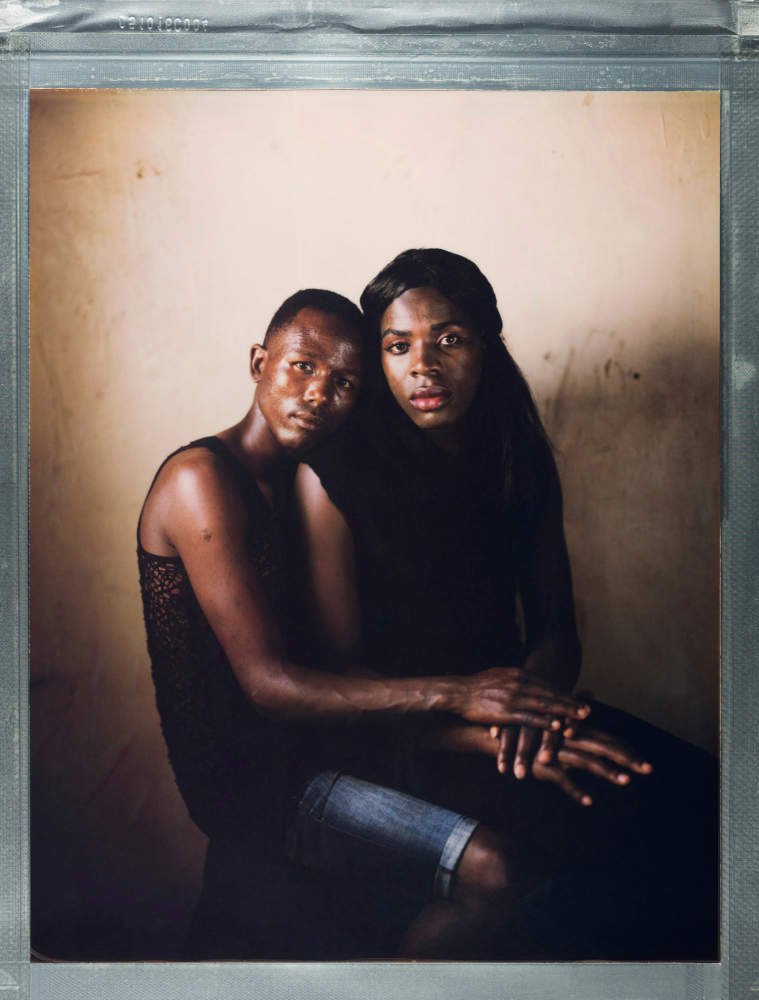

Lucky & John

Lucky (right) and John (left), Ugandan refugees living in Nairobi. Lucky and John lived together in Uganda until John’s parents found out they were in a relationship and attacked Lucky. They hid with a friend and saved enough money to flee to Kenya.

They were registered separately as refugees and they were able to find some sanctuary with NGO Nature Network. “The life now in Nairobi, because of the Nature Network we have, the little money we are getting, it help me someway, somehow, and the Nature Network come in, they do pay us rent here, they buy us food.”

Faith has been an important part of keeping them strong through their trials. “If it wasn’t God’s help, we would have already died, because I remember the time when the parents came to attack him [Lucky], and then, they wanted to kill him, if it was not God, he would have already died, but God knows us, God loves us, so he managed to protect us all the way from Uganda up to here, we are together.”

Tasha

Tasha (21), a Ugandan refugee living in Nairobi where she is supported by NGO Nature Network.

Tasha is a transgender woman who presents as female, because of this she is often targeted and she does not often leave the apartment where she lives. “As a transgender, I’m always indoors. Me, I never move out. I’ve never enjoyed my life here in Nairobi, that is what I have to tell you. Because from Monday to Monday, from January to January I’m always indoors. I only move out if it’s really important, very-very important, because I’m scared for my life. Being in the same place, same house, same room from today, tomorrow, the other day, the other day, daily. It really bothers our mind and then you are all there. You feel like you’re being tortured in a way, so you’re not free to do what you want. At times you feel like you wanna take poison.”

Tasha explains how many Ugandan refugees end up in sex work in order to be able to afford food and shelter. “I personally, I’m not doing sex work, but most of the people, most of my refugee friends are engaging into sex work. Because they want to earn a living. And most of the people that are engaging into sex work are getting different diseases like HIV/AIDS… We’ve had people, refugees, in fact here, Ugandan refugees dying of AIDS because they have gotten it here in Nairobi. And most of the time when they get these diseases because as for refugees we cannot afford the hospitals and stuff. They end up getting so sick, very ill and we cannot treat them. At the end of the day they end up losing their life because of practicing sex work. They never want to disclose it to anyone, because they are scared of discrimination… I don’t wanna lose my life. I’m still young. I still have a future out there. I wanna do something for myself. I wanna stand out for other LGBTI people.”

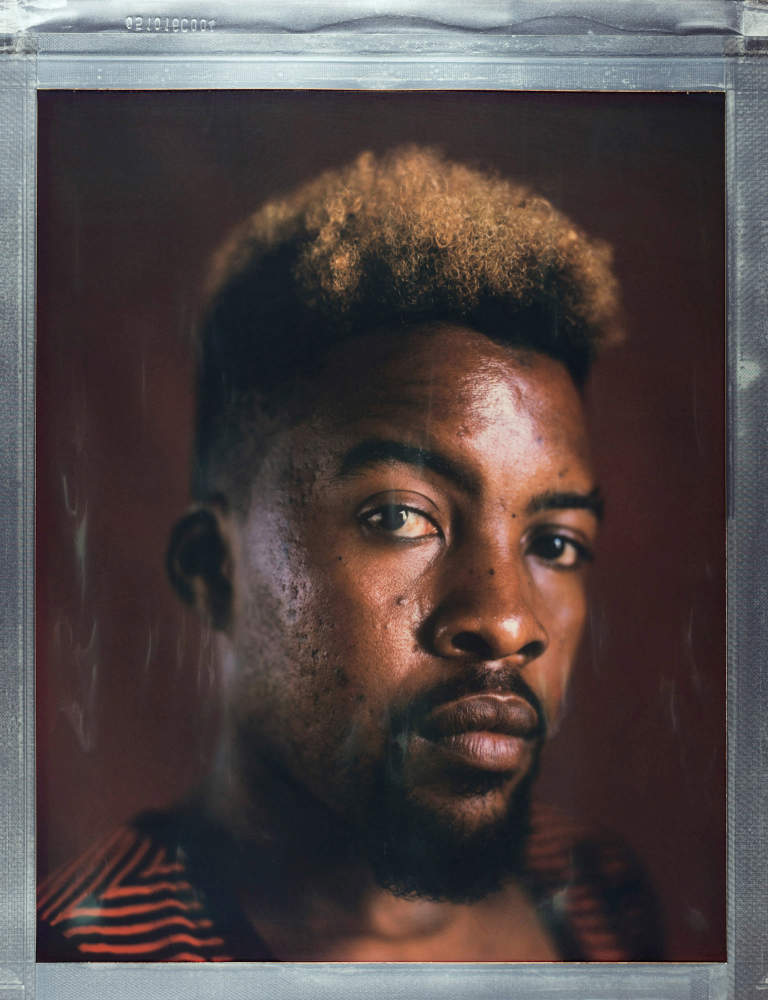

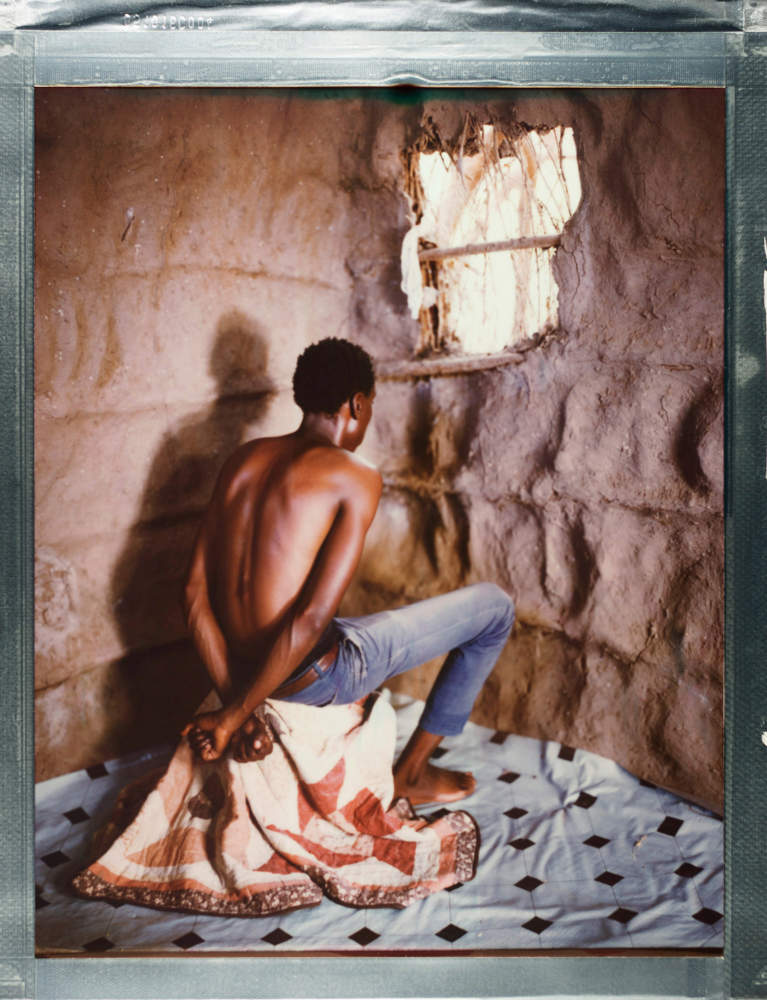

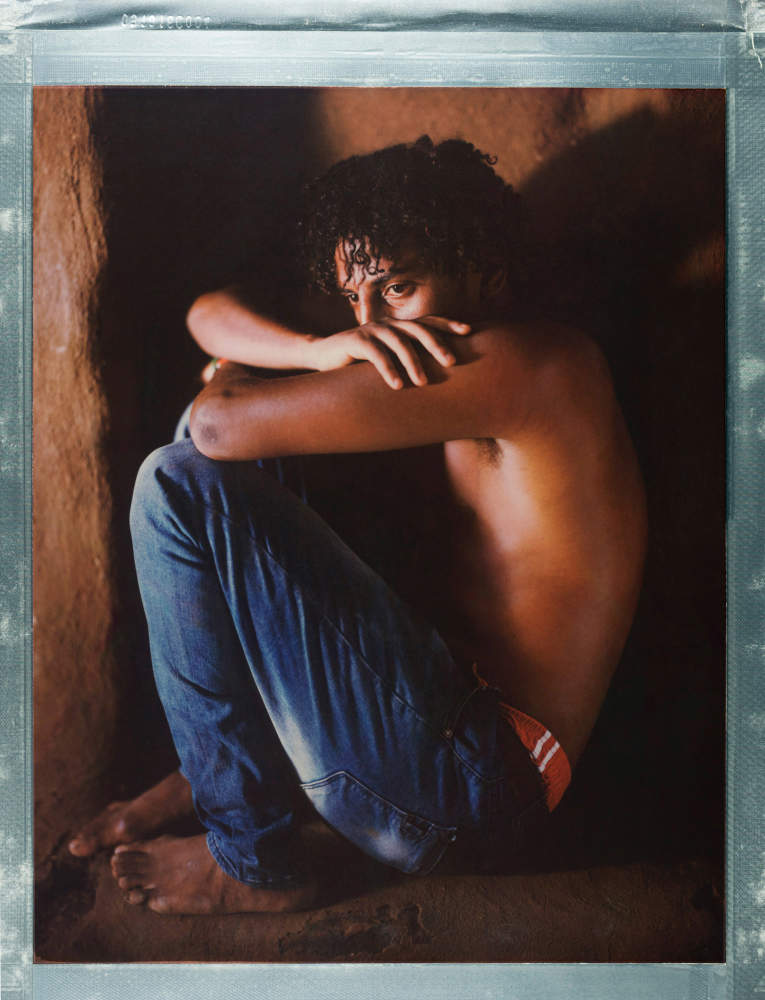

Gregory

Gregory (not his real name) is a Ugandan refugee living in the Kakuma refugee camp in north western Kenya. Gregory was forced to leave his community after he and his partner were witnessed having sex. “My uncle was angry about it. He decided to abduct me, with the help of some of my family members. They took me to a mud house in the village for two days. I was screaming for help, mercy. Cattle keeper heard me, broke in to rescue me. I ran away the same evening. I had no other option, but to cross into Kenya.”

Gregory was tested HIV positive in Kenya and has found that accessing medication and adequate diet is a challenge as a refugee unable to work and obtain funds to maintain his health. “Due to poor feeding, the medication makes you dizzy. You wake up weak, feeling dizzy. You feel your head is spinning around, because last night, you didn’t eat, because the doctors tell you should swallow the ARVs when you’re going to sleep. Then, in the morning, you take suppository, so you wake up with the dizziness of the ARVs. And you take that when you don’t even know what you’re going to eat. You have to stay in the house. The house is hot. You’re dehydrating. So, makes you weak in that way. If you go to the clinic to pick up some medication, you walk in the scorching sun, because this is a semi-desert. The degrees are very high. 40+. You walk an hour. You dehydrate. Then, an hour back to where you live. So, it’s kind of frustrating. Transportation, poor feeding, the environment. Everything is challenging.”

He says the conditions are made even more challenging because of the stigma of being HIV positive. “People discriminate people who are HIV positive, and mostly, in Africa, they see that as a curse. They even call it bad luck.”

Joseph

Joseph (not his real name), a Somali living in Kakuma refugee camp in north western Kenya since 2004. Joseph was ostracised by her family for ‘behaving like a girl’. Joseph identifies as both gay and a trans woman. Homophobia in Kakuma refugee camp is a great source of insecurity, says Joseph.

Speaking of two of her gay friends she says “One of them has been killed and another friend has been tortured and has escaped the place.” The constant persecution and insecurity weighs heavily on her, as does her positive HIV status. “I had the HIV for two years and I never talk to anyone about the disease… HIV people are not welcome in the camp, those are reasons why I was hiding my disease from others for long.”

Talking about her state of mind she says. “I am expecting nothing from this world , there is no cure for this disease and it killed many people. At the moment I am just waiting for death. I have the disease. I could not go to the hospital for treatment. I was persecuted by everywhere even inside the hospital. The local government and NGOs could not help me but I am still alive, I still cannot believe that I am still alive with the disease.”

Jonah, an LGBTI Ugandan refugee, who lives in Nairobi and is supported by Nature Network. After Jonah’s uncle, who he lived with, discovered Jonah is gay, he attacked him. “My uncle came to our room, dragged me from the bed. On top of his voice, saying ‘I’m a disgrace, I’m a curse, I’m a criminal that needed to be killed’. He went to the kitchen, and got a big wood, and started beating me with it. I bled. He campaigned other people to beat me up, and here, some neighbours came to rescue me, ’cause they wouldn’t let me be killed in the neighbourhood.”

“The challenges I face here in Kenya, we happen to be given the 4500KSH [GBP 34.50] every month which happen to be not enough, ’cause the life of living in Kenya is a bit expensive, so people tend to engage in sex work as a way of generating income to supplement on the money being given. We have a problem of health. When someone falls sick, and the way the UN guys respond to it, it’s on a slow pace, ’cause you have to email to them, go to the UN offices a couple of times, and you know all during that time, you’re in pain, and they keep on giving the appointments, so if it’s not amongst your friends to mobilise and get you money, and you be treated, some of our friends have died. I have a couple of friends who are passed on, and then, my other problems are, since so many people have been engaging in sex work, so many of them have been infected, and a number of them have died of AIDS.”

Ali

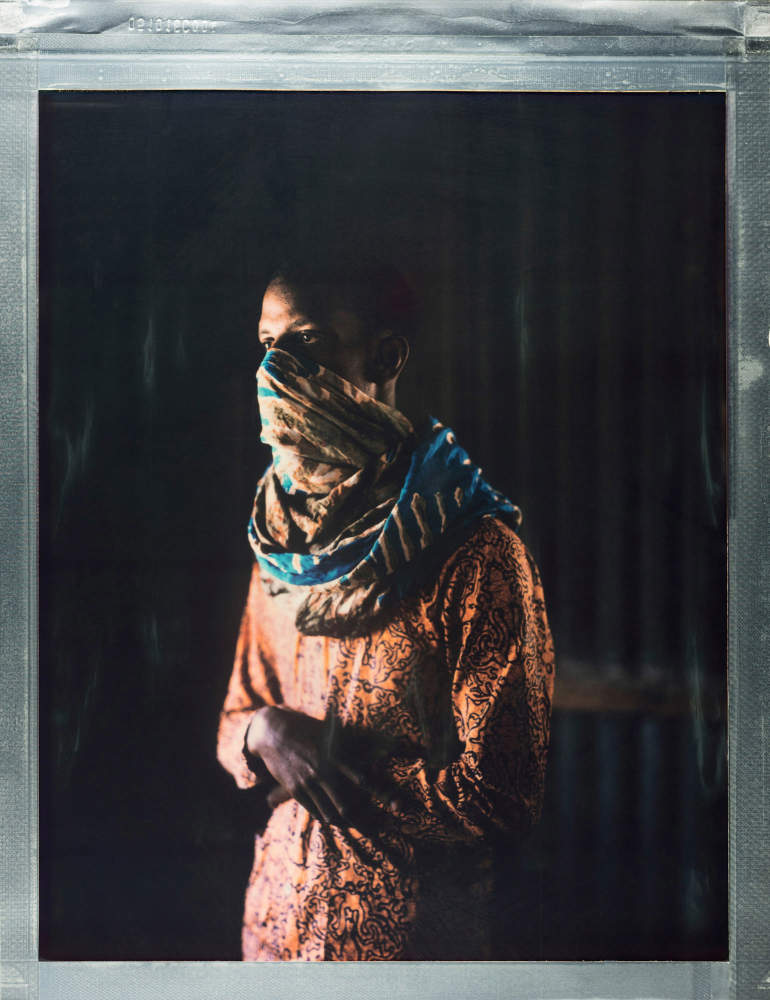

Ali (not his real name), a Somali living in Kakuma refugee camp in north western Kenya since 1997. He is gay.

He describes the lengths he has gone to in order to hide his sexuality, and stay alive. “I got married because I didn’t want people to know the truth about me. If they knew they would have killed me. They would have killed my family also. According to our Muslim religion such kind of person is killed. I have kept it a secret so that people won’t know. That is why I got married. I wouldn’t have been here if I didn’t get married.”

Ashiraf & Kajjan

Ugandans Ashiraf (23, right) and Kajjan (23, left). Ashiraf identifies as a transgender woman and Kajjan as gay. While same sex marriage is not legal in Uganda, in 2015 the pair got married in a hotel.

“We had happiness at the party” says Ashiraf, and then adds “and that was the day.” That was the day their new married life began, and also the day their lives changed for the worse.

A friend took photos of the wedding and posted them on social media. Local newspapers got hold of the photos and published them. Two weeks later their neighbours recognised them in the newspaper and went to the police. A mob attacked their house. “They said a lot of stuff, that we are sons of evil, we need to go to hell, we shall kill them direct if we get them.” That night they packed their bags and left for Kenya.

But life in Kenya was not what they had hoped. They struggled to be registered by the United Nations refugee agency, and struggled even more to find a place to settle down. “After three months in Kenya, our life was not good at all, as we kept on migrating from one place to another because Kenya is like Uganda they don’t allow us in here. We were beaten, abused, tortured on the way when we were moving,” says Ashiraf.

“My boyfriend is HIV positive and I am negative but I have (high blood) pressure. Life is hard because we don’t have money to eat yet we have to take our medicine. The landlord is chasing us out of the house because we don’t have money. I tried to look for jobs but couldn’t get because I naturally look like a transgender. Whenever I go to look for jobs I am abused that I am a lady, sometimes beaten.”

Kajjan agrees – “Up to present time, we are still suffering because I am HIV positive though my boyfriend isn’t, we have nothing to eat, nor food.”

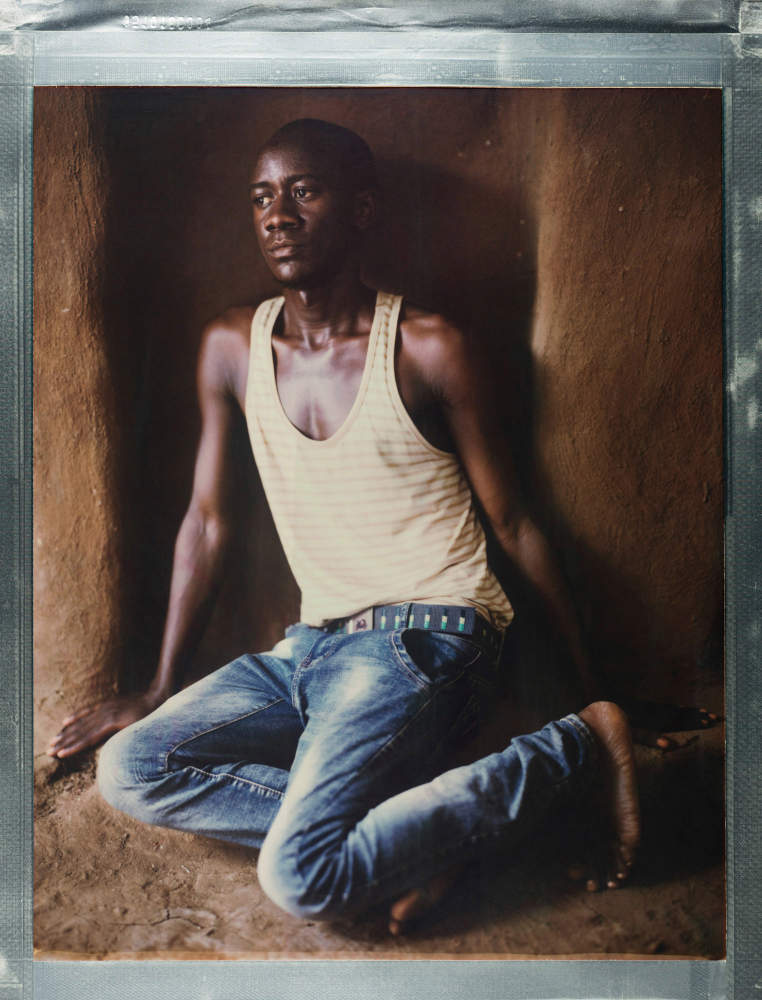

Aaron

Aaron (26), a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo living in Kakuma Refugee Camp in north western Kenya.

When his community learned that he was LGBTQI+ they targeted his family. “At one time, my family could be attacked by police and they could be imprisoned. I could be tortured, I could be beaten sometimes. And then, one time, my family was attacked in the middle of the night. They came at my home. They kicked the front door of our house.”

“They entered, searching for me. I sensed there was danger and I had to slip through the door of the back house of our house, and I ran away to the bush. I don’t know what happened to my family. And I ran into Uganda. I ran from Uganda to Kenya. Right now I’m here as a refugee, and I’m living in Kakuma Refugee Camp. That’s the end of my story.”